I enjoy blogging conferences, and I especially enjoy blogging TED. And while I’m pretty good at conferenceblogging, blogging my own talk is beyond me. So here are my notes – I can’t promise that what I say on stage will bear any resemblance to this, but this is what I’d planned to say. The slides are available at Slideshare, and if all goes well, I hope we’ll see video of the talk online in the next weeks or months – I’ll keep you posted.

As an American, I try to avoid forms of football that don’t involve men larger than me tackling each other, but it’s been hard to avoid the 2010 World Cup – when I go on Twitter, there’s been lots of unfamiliar terms in the trending topics list: “Vuvuzela”, “Furia Roja”, “Octopus”…

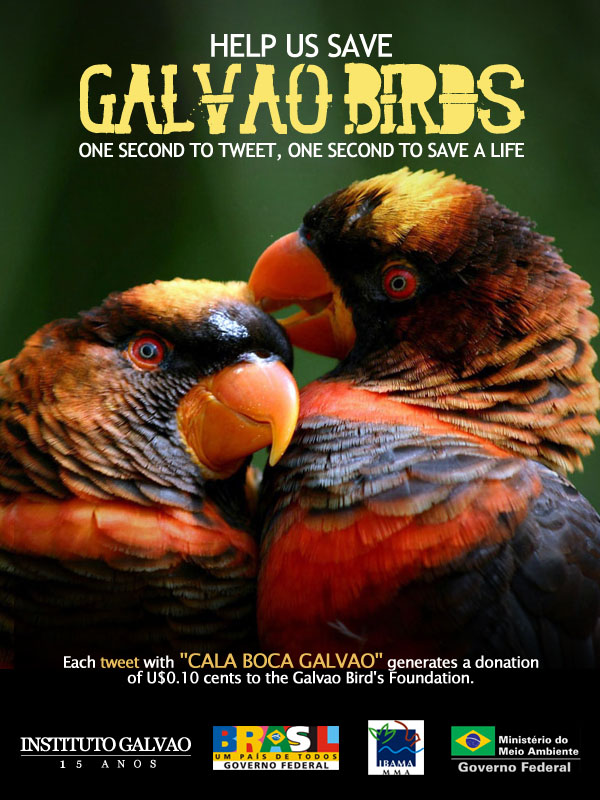

For a couple of weeks, the leading topic on Twitter was “Cala Boca Galvao”. Being a monolingual American, I obviously didn’t know what this meant. Fortunately, a number of helpful Brazilian twitterers were happy to enlighten me. They explained that “Cala Boca Galvao” actually means “Save the Galvao” and was the rallying cry for an international campaign to save the rare Galvao bird…

which is in grave danger of extinction. (This video helps explain the bird’s plight – it’s very much worth your time. :-)

Actually, it’s a very sad situation – the Galvao bird isn’t just very beautiful, it’s evidently got narcotic properties, which have led some troubled individuals to engage in shocking acts of Galvao abuse.

Fortunately, people are stepping up to help. Lady Gaga has evidently released a new single – actually, several new singles – titled “Cala Boca Galvao”.

And as it turns out that the reason so many people were twittering “Cala Boca Galvao” – and the reason I should tweet it as well – is that ten cents would be given to the foundation to save the Galvao if I did so.

This was, of course, a prank – a very successful one. There’s no Galvao bird, no donations, no new Lady Gaga single, and I can’t speak to what Diego Maradona may or may not be snorting. Galvao Bueno is the football commentator on Rede Global, and his commentary evidently annoyed the Brazilian twitter users enough that they organized a campaign to tell him to shut up: “cala a boca” means “shut your mouth”.

There’s a couple of lessons to take from this story. One is that the Brazilians are threatening to take the lead from the Americans and the Japanese in terms of engineering new internet memes, which might mean more inexplicable capoeira jokes and fewer Pokemon references, which can only be a good thing.

And it’s a reminder that you can’t go wrong online asking people to join your protest – no matter how silly it is – so long as all they have to do is cut and paste a phrase.

But the lesson I’d like to point out is that the world is much wider than we generally perceive it to be.

About 170 million people visit Twitter each month, and 19m (11.2%) are Brazilian. More than one in ten Brazilian internet users visits Twitter each month, which is a higher proportion than in most nations – of the big internet using nations, the only one with a higher percent of people using the tool is Japan.

There are millions of Japanese and Brazilian people on Twitter. If that seems surprising to you, it’s because most of your friends online aren’t Japanese or Brazilian. Twitter conducted a phone survey that revealed a quarter of their US users are African American… which was pretty surprising to most American users, who assumed that Twitter was just used by nerdy white guys.

What’s so surprising about this is that a picture of African-American twitter is just a click away – Twitter’s trending topics usually aren’t about the world cup – they’re often conversations led by African-American twitter users. Fernanda Viegas and Martin Wattenberg – a pair of visualization experts who created IBM’s ManyEyes software – examined a set of Twitter tags over a weekend in May and discovered that there’s a heavy degree of racial segregation in Twitter use… and not just in ways you’d expect – “cookout” was a term mostly used black twitterers, and “oil spill” was a predominantly white topic.

Tools like twitter – tools that give us a view of the world through our friends – can trap us within what my friend Eli Pariser calls “filter bubbles” – the internet is too big to understand as a whole, so we get a picture of it’s that’s similar to what our friends see. If our friends are Brazilian, or know some Brazilians, perhaps we got the joke about Cala Boca Galvao very quickly – if not, we miss it. The wider world is a click away, but whether we mean to or not, we’re usually filtering it out.

This wasn’t how it was supposed to work.

In 1995, Nicholas Negroponte, then the director of MIT’s Media Lab, began his book “Being Digital” with a story of how atoms are different than bits. He’s attending a meeting on the future of the US technology industry, and he can’t get his head around the idea that the water on the table in Florida is from Evian, France – someone’s gone through great trouble to move these heavy glass bottles filled with heavy French water all the way to the US. The future isn’t about moving, selling and trading these heavy atoms – it’s about the movement of weightless, speedy bits.

On this point, it turns out that Negroponte was wrong. In 2010, it’s frequently the case that atoms are more mobile than bits.

Fiji Water is now challenging Evian for leadership in the American “imported bottled water” category – and I’ll spare you the rant about the absurdity of that particular category – and simply mention that you’re a hell of a lot more likely to encounter water from Fiji on any given day in the US than you are to encounter news from Fiji, never mind film or music from Fiji, despite acute political injustice taking place in the country.

The infrastructures of a globalized world lead us to believe that we’re living in a flat, Friedmanesque world. From London, Bangalore’s just one hop away, and Suva’s just a hop further.

Once we stop looking at the infrastructure – the roads, the air routes, the shipping lanes, the cables – and start looking at the flows of traffic, it becomes very clear that some parts of the world are far more connected than others. Globalization is unequally distributed. London and New York are a whole lot closer than Johannesburg and Rio.

I’ve spent much of the last decade studying how news media pays attention to the world, because there’s a phenomenon I find deeply unsettling.

When I was growing up in the US the 1970s, 35-40% of an average nightly newscast focused on international stories. The percentage of international news in an average newscast now 12-15%.

As Alisa Miller, the president of Public Radio International, pointed out in a TED talk in 2008, this can lead to a rather distorted picture of the world. The image her talk centers on is a cartogram – it’s a map that’s been distorted to display a variable, scaling a nation in terms of the media attention it’s received.The attention to the US, and to a very small set of other nations, creates a few bulges of interest and vast areas of no coverage at all.

Before you dismiss this as being merely a problem of American television news – which I agree is dreadful – let me tell you that I’m seeing the same phenomenon in top quality American newspapers like the New York Times, which pays far closer attention to wealthy nations than to poor ones, which means that you’re more than 8 times as likely to find a story on Japan in the Times as you are one on Nigeria, despite the fact that the countries have comparable populations

Most media I’ve mapped show this GDP bias. The BBC shows a different bias – the coverage of poor countries that used to be part of the British Empire is excellent, while the coverage of those that weren’t formerly pink on the map tends to be weak.

My hope was that the rise of the internet and digital media would mean we’d see a wider picture of the world because it’s so much easier to report from overseas than it was three decades ago – instead of shipping film footage from a war zone to the UK to have it developed and then broadcast, you can post video to youtube.

There are notable exceptions – bloggers paid very close attention to the green movement in Iran, for example – but my research suggests that the most popular bloggers are at least as tighly focused on these wealthy, high attention countries as mainstream media. There’s lots of bloggers from the developing world online – infrastructure – but very little attention – flow – going to their sites.

And the media we’re collectively creating on sites like Wikipedia shows these sorts of biases as well – this is a study done by Mark Graham at the Oxford Internet Institute down the road, showing articles on wikipedia that have geocoding information. It gives a sense for some of the geographic biases we see on wikipedia as a whole, and the strength and weakness of the project in covering different parts of the world, though it’s not the same as a map of all articles by geography in Wikipedia and may overstate the disparities I’m trying to point out here.

The promise of the internet – the idea that everything is just a click a way – is that, here in Britain I can read newspapers from Australia, India, Nigeria, Ghana, Canada, at no cost and end up with a wider view of the world. The truth is that – on average – I won’t. I analyzed data from Doubleclick Ad Planner, looking at the top 50 news sites in each of thirty countries – in the UK, over 95% of traffic to the most popular news sites is to domestic sites. It’s one of those rare cases where the US can accuse the UK of being more parochial than we are – we like the BBC, the Telegraph, the Guardian, and as much as 6% of our news readership is of British media. But it’s not just the US or the UK – you’ll see that 94% of news read by Indian internet users – who are on average a lot wealthier, worldlier and English-literate than the average Indian citizen – spend 94% of their time on domestic news sites.

It’s data like this that’s leading me to conclude that the internet isn’t flattening the world the way Nicholas Negroponte thought it would. Instead, my fear is that it’s making us “imaginary cosmopolitans”. We think we’re getting a broad view of the world because it’s possible that our television, newspapers and internet could be giving us a vastly wider picture than was available for our parents or grandparents. When we look at what’s actually happening, our worldview might actually be narrowing.

Having this wider picture of the world is critical for global survival. In the course of four days at TED, we’re going to hear about problems like global warming, pandemic, collective security that can’t be solved by individuals or by nations acting alone – they’re global problems and they’re going to require global solutions. And because the theme of the conference is “The Good News”, it’s worth pointing out that the most exciting opportunities – to make a difference, to make something beautiful or to make a profit – are global in scale. We need to build solutions based on massive, transnational cooperation, which needs to begin with dialog that crosses linguistic, social, national lines

So here’s the good news – we’ve got the tools we need to do this, the infrastructure that could make the world a wider place. And we’re starting to figure out what we’d need to do to build connections around the world that are real, not theoretical.

For the last six years, one of the central joys of my life has been being part of the Global Voices community. This group of bloggers from around the world has been focused on reforming the world’s media by amplifying voices we don’t hear very often – the voices of people in the developing world who are expressing themselves online. You’ll be surprised, I’m sure, to learn that we haven’t yet reformed all of global media – it’s going to take a few more years, I suspect. But what we’ve learned is that there’s a couple of techniques that are critically important if you want to get a picture of a wider world – and more importantly, if you want to build tools, systems and institutions that help people experience a wider world – these turn out to be helpful tools

Cast a wider net: Raising Voices

First, it’s worth remembering that the world wide web is hardly worldwide. This composite picture of the earth at night is now a decade old, but it still serves as a pretty good portrait of the 1.8 billion people who are online and the 4.8 billion who aren’t. (This image, by the way, appears to be a mandatory part of each TED conference – I just hope I’ll be the first to show it this year…)

Those dark spots on the map aren’t silent – they just tend not to be well represented in the world’s media. Through Global Voices, I have a lot of friends in Madagascar, and I can tell you that one of the central annoyances in their lives is being better known for the Dreamworks film than for the natural wonders of their nation

Foko Club didn’t start as a project to change international perceptions of Madagascar – it began as a club for high school students to learn English. That turned into a club for people interested in the internet, which became a blogger’s club, which spread nationwide.

Foko became something else in early 2009, when Malagasy politics descended into chaos as the mayor of the largest city, Antananarivo, overthrew the president with the backing of the military. The new government silenced most independent media, the online space was one of the few places where people could report on the demonstrations and suddenly the high school students associated with Foko were reporting breaking news with their blogs and cellphone cameras. If we want a wider world, we’d find ways to raise voices in places we don’t often hear from, like Madagascar

Translation: Distributed, human, transparent, default

Here’s the trick – you probably don’t speak Malagasy. Even if you do, the internet is becoming a profoundly polyglot space, which means that, while there’s more content online every day, there’s a smaller percent of the internet that each of us, personally, has access to because more is in languages we don’t speak.

When we encounter words we don’t understand – either in the real world or the online world – we tend to ignore them. And the internet is wired to ignore them as well – search Google for “apple” and you might get Spanish language pages with the word “apple” in them, but you won’t get ones with the word “manzana” or “ringo”.

In their new web browser, Chrome, Google did something very smart and subtle – they detect the language of the page you’re looking at and offer to translate it for you. You can set the browser so that it always translates Chinese for you… which means that if you follow a link to a Chinese-language site, you don’t automatically hit the back button as soon as you see incomprehensible characters

The problem is that Google’s using machine translation, which is pretty impressive between English and French, and pretty painful between English and Chinese. What I want is a button that lets me request a human translation of a page I’m interested in and either pay someone via Mechanical Turk to publish that translation, or let a volunteer know that there’s someone who wants to read that page in translation.

It turns out that volunteers are capable of translating far more than you might imagine. This is Zhang Lei, who was living in the US during the run up to the Beijing olympics, when there was a lot of US media scrutiny focused on China’s human rights record in Tibet. Lei felt like the language barrier between Chinese and English speakers was leading to a lot of conflicts that were unnecessary, so he started organizing friends to take on the task of translating influential English-language media into English

Yeeyan’s got 150,000 registered volunteers, and they publish 50-100 articles each day, featuring content from The New York Times and sites like Read Write Web. Before they were briefly shut down by the Chinese government, they had a partnership with the Guardian to provide the official edition of that newspaper. So here’s my question: where’s the English-language version that’s giving us insights into what’s being said in Chinese media? If we want a wider world, we’ll take translation seriously, and work to make it routine, transparent and by default

Filter failure: How curators overcome the flock

So we can imagine a future where projects like Foko help us hear voices from all corners of the world, and where Yeeyan translates into languages we understand. How do we decide what to read?

The world’s far too big for any of us to experience personally, and the internet’s at least as overwhelming. YouTube recently announced that people are posting 24 hours of video each minute of each day – if you wanted to watch a day’s worth of videos, it would take you almost four years, and that’s without stopping to sleep, use the bathroom or get the psychotherapy you’d desperately need. We need filters so we can cope with all this information.

We tend to use two types of filters to manage the internet – search, which is great at telling us what we want to know, and social, which promises to tell us things that we don’t know we want to know. There’s a lot of people trying to engineer serendipity by taking advantage of the fact that not only are you on the internet, your friends are also on the internet. And if your friends – or just someone with similar interests – finds something that’s interesting, it might be a serendipitous discovery for you as well.

There’s just one problem with this method. Human beings are herd animals. Like birds of a feather, we flock together. And so what you see on a site like Reddit or Digg – or what links you get from your friends on Facebook or Twitter – is what the flock is seeing. The flock might help you find something that’s unexpected and helpful, but it’s not likely to find you something from halfway around the world.

Meet Amira Al-Hussaini. She’s the editor for the Middle East and North Africa for Global Voices, and she’s got one of the hardest jobs I know of, which is helping distill the chaos that is the middle eastern blogosphere into a couple stories we publish on the site. Oh, and she’s got to do it a way that makes the people she’s representing – Israelis and Palestinians, Syrians and Iraqis – feel represented fairly. But her toughest challenge is finding the story that’s going to capture your attention, either because it’s funny, or surreal, or moving or just beautifully told.

Helping you find things that are fascinating, but outside of your normal orbit is what a good DJ does, or a museum curator, or an editor. The people who are good at it are experts – they’ve got a deep understanding of what you know, what you don’t know and what you might like to know. It’s hard to automate – I think it might actually be impossible to automate – and that’s okay – the internet can superempower curators, letting them help much larger audiences stumble on serendipity. For a wider web, we need this third form of filtering – we need search, social, but we also need these shepherds to help us break out of our flocks and find different voices.

Putting it into context: Bridge figures

When we hear voices from undercovered parts of the world, when we’re able to read voices in other languages, when skilled curators push us outside our comfort zones, we find can find ourselves in some unfamiliar territory.

This image is from of one of the internet’s best technology blogs, Afrigadget. The blog features a wide range of hackers on the African continent, from software developers to blacksmiths. The message of the blog isn’t to teach us how to make a cold chisel out of the drive shaft of a land rover – it’s to teach us something about how reuse can lead to creativity and how people innovate from constraint.

To get that sort of message, we need context for an image like this one. And for context, we need a guide.

Erik Hersman is the founder of the Afrigadget blog. He’s an American geek, who’s the COO of an award-winning and influential software company. He’s also an African. He was born in Southern Sudan, went to high school in Kenya, speaks fluent Swahili. He’s a guy who’s got one foot in each of two worlds, and he’s passionate about explaining each of those worlds to the other. Erik is a bridge figure, and he’s the rare individual who can get American geeks interested in Kenyan blacksmiths and vice versa, because he understands both worlds and can build links between the two.

If we want a wider world, we need to celebrate, recognize and amplify the influence of these bridge figures.

And we need people to walk across these bridges.

If I played linebacker in the NFL, I think I’d probably spend my offseason nursing my wounds and spending my money. Dhani Jones spends his time traveling to different countries and finding different athletes to train with and learn from. He’s got a show on the Travel Channel that’s pretty remarkable – not just because it’s fascinating to watch a professional athlete learn the skills required to play water polo or fight muy thai. It’s fascinating because Dhani is somehow able to project a sense of openness, good humor and approachability that lets people connect with him in whatever country he’s visiting.

Dhani’s a xenophile – a person who puts in the hard work needed to cross bridges and interact with a wider world. I watch him because he’s an inspiration as well as a teacher as I learn how to experience the world in all its diversity and complexity.

My challenge to you in this room isn’t just to be a xenophile or to be a bridge – most of you already are, or you wouldn’t be at a conference focused on ideas from around the globe. My challenge is this – help me figure out how we build the new tools, reform the educational systems, immigration systems and government as a whole so that we empower the people who want to make the world wider. How do we cultivate xenophiles, celebrate bridge builders and rewire the media so we’re experiencing a wide world and not just our flock? That’s what I’m working on and I’d love your help.

Wonderful and inspiring. Thanks for this.

~Firuzeh (GV author Puerto Rico)

Pingback: links for 2010-07-14 « Communications for Development

Pingback: Putting people first » Internet’s vision ‘not realised’

Pingback: SJ’s Longest Now » Blog Archive » Zuck Strikes Back at Systemic Bias

Pingback: Get Out of the Echo Chamber to Improve Innovation « Innovation Leadership Network

Pingback: Doc Searls Weblog · The Mall Wide Web

Thanks for the mention and the great insight!

It is also important to point out that it is the entire Global Voices team covering the Middle East and North Africa who allow us to do what we do, in good times and bad times, in health and sickness …

It really is a blessing to be working alongside the best of the best!

Pingback: Ethan Zuckerman on Global Media | test title

Hi Ethan,

Great presentation, as has come to be expected. One question–how can we find new ways to value time on sites which can generate income for those creating the sites? Open source is wonderful AND everyone needs to eat, content creators, students, shoppers,lawyers, blacksmiths, TED presenters, etc.

Glboal Voices is amazing,too. Global passports anyone? Is the UN reading/listening?

Sher

Pingback: FutureEmergency.com

Only right if this post was translated so the french translation is here:

http://www.madagascar-usa.com/2010/07/un-monde-plus-vaste-un-web-plus-vaste.html

Read your notes one day and have seen your presentation the next! What a thrill that is. I thought you did brilliantly. Lots of information and room for thought. Hope you received positive response from the audience and fellow TEDsters.

a good level of self-containment and elitism is nothing new for the net, actually was widely discussed and experienced since late 80s-early 90s in the US (compuserve, newsgroup or even on the WELL) and it’s still quite evident today in many “walled garden” communities/places, facebook included

more recently cass sunstein, among other scholars, talked/wrote about the “media that reinforce their own views and citizens that carefully filter out opposing or alternative viewpoints to create an ideologically exclusive ‘Daily Me'”

and the self-congratulatory, tightened-loops or pseudo open discourses of most national blogospheres are also well known issue

so let’s not forget that those traits have a (relatively) long history and some common roots, even beyond the old-fashioned white western middle-class geeks — and sometime it’s not that easy to notice and overcome such burden that even some “new globalism projects” still carry on one way or another…

and even if we personally try to be persons-bridges, and even if it’s true that GV is a good tool for that, it is still crucial to have an inside-out & on-going process to identify these old burdens and try to get rid of them as a collective rite of passage — which sometimes i feel it’s not happening, not even within GV right now, at least not with the awareness and strength and passion necessary to actually “empower the people who want to make the world wider”…

Thanks for this great talk. The visualizations on the adjacent conversation bubbles on Twitter and the flight patterns to the Southern Hemisphere stuck with me. Why aren’t there flights from South America to Africa, anyway?

It prompted some soul searching, too. Why don’t I read anything more foreign than the Guardian? or once in a moon Al-Jazeera? Why don’t I have more truly cosmopolitan friends? Hell, why don’t I have more conservative friends?

In a global world, I am still a local- my life happens right here and the direct impact of local things means more day to day. The planetary interconnections are beyond my scale- Brazilian Favelas and coffee plantation slaves are just an idea, until I have a direct sensory experience, they won’t stay in my consciousness when I am buying that latte.

Do you notice this phenomenon: if I have physically been in another place (such as Istanbul or Teheran), It awakens an ongoing presumbalu ego-fed interest in those locations, those people. From that Tehran visit forward, I will read news articles on Iran with some imaginary pipe and scholarly gaze, as if I knew or cared what was going on there- thinking of the people I met and the dusty streets and the smell. But it is not the same with the abstraction of a place I haven’t physically connected to. That was one of the pushes behind the Peace Corps, and so many youth exchange programs.

Also, even when I do get to go somewhere, talk to locals, try to understand- I often find my cultural biases so strong in some areas, that it would not matter if the news feed or the local viewpoint was a correct and balanced translation, some things are so alien to absorb (for example- women’s rights from dress to physical restrictions in the Islam practiced in Saudi Arabia).

Anyway, love the bridge building talk, and will try to reach beyond my solipsistic conversations and media channels in the coming weeks, and maybe even get on a plane and see something new that makes me uncomfortable.

Geekcorps created many bridges. Thank you for that Ethan.

Pingback: vps free hosting » Zuckerman on Xenophilia and bridging

Pingback: Jillian C. York » Is Vaseline’s Skin-Lightening App Racist?

Pingback: “A wider wolrd, a wider web” « Run, Motherfucker, run

Juan Cole provides the service you describe to some extent at Informed Comment

http://www.juancole.com/

It’s selective, but I think he’s tried to meet the need you describe.

Pingback: “Cala Boca, Galvão” derrubando as fronteiras globais | Nando Pax

Great presentation and great message,

it’s became one of my favourite talk!

your TED talk, it’s already available in spanish!

Vero

Pingback: Under-depreciated… | The Building 5 Chronicles

Pingback: Cala Boca Galvão no TED Talk 2010 | NerdsKamikaze

Pingback: Save Galvão Birds Campaign (CALA BOCA GALVÃO) | NerdsKamikaze

Pingback: “The immaterial global village”: debunking myths of the internet

Pingback: Summer Reading | The CamBlog

Pingback: Campanha Cala Boca Galvão - Fernando Motolese

Pingback: Cala Boca Galvão Videocase - Fernando Motolese

Comments are closed.