I’m just back from my summer roadtrip with my sweetie, visiting some of the great legacy cities of the Great Lakes region. Our destinations – Utica, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, Detroit, Toledo, Cleveland, Erie – either sound like the punch line of a joke about unlikely vacation destinations, or a comprehensive tour of transformed and transforming industrial cities. We had a sense of humor about the trip – we played Randy Newman’s “Burn On” more than once as we navigated our way through Cleveland – but there was nothing ironic about our itinerary, and it was one of the most satisfying and fascinating trips I’ve ever taken, home or abroad.

Even as I approach fifty, I sometimes deceive myself about who I am. For a week deep in this past winter, I fantasized about a roadtrip in a camper van, waking up to dazzling sunrises in a wide array of National Parks. I began researching the (significant!) costs of renting a van and considering what parks we might want to hike in. I shared a possible itinerary with Amy, who reminded me that she considers camping grounds for divorce, and pointed out that I rarely hike, despite living in the midst of lovely, gentle mountains. Who was I fooling imagining that renting a van would turn me into a mountain man?

(This is why people who’ve known you for decades are so important.)

And so I lay awake one night thinking about what Amy and I actually do on vacation when left to our own devices. It’s pretty simple: we explore museums; we buy weird crap in junk stores; I photograph decaying buildings; we eat cheap ethnic food. Turns out you don’t need a camper van to do any of those things. What you do need are legacy cities.

Factory, Rochester, NY

“Legacy city” is a term coined by The American Assembly, a non-profit organization associated with Columbia University. It’s meant as an alternative for the more fraught terms like “rustbelt” or “post-industrial” cities, and emphasizes two valuable meanings of the term

“legacy”. On the one hand, the architecture, institutions and history of these cities are valuable legacies, from the stunning buildings of Detroit’s downtown to the treasures in the Cleveland Museum of Art. On the other hand, legacy invokes “legacy systems”, architectures that have outlived their usefulness and need modernization or replacement.

Generally speaking, legacy cities have shrunk, or are still shrinking, sometimes dramatically. Detroit’s population is down almost two thirds from it’s 1950s peak, shrinking from 1.85 million to 640,000. Cleveland peaked in 1930 at 900,000 and is now at 370,000. Buffalo peaked at 580,000 in 1950 and is now at 278,000. As we moved through unfamiliar cities, we began looking at certain key factors to understand what sort of landscape we were moving through: How much had this city shrunk? What was its peak decade? How sharp is residential segregation? It is a refugee city?

Nepali Flag mural on the side of a junk store, Erie, PA

This last detail was especially fascinating to us, as one of our major goals of the trip was eating excellent and unfamiliar food. Many legacy cities have welcomed refugee populations to take advantage of inexpensive housing stock. As a result, there’s Bhutanese butter tea and Nepali food in Erie, PA, Bosnian markets in Utica and an astoundingly good South Sudanese restaurant in Buffalo. These refugee cities are different from immigrant cities in that the people who’ve resettled them are often fleeing persecution – we realized this as we wandered a Burmese grocery in Utica and discovered many of the customers in hijab. (Myanmar is majority Buddhist and Rohingya muslims have been subject to ethnic cleansing.)

How does a city shrink? How does it rebound?

We live just outside Pittsfield, MA, a city whose population peaked in the 1960s at 58,000 and continues to shrink, now below 44,000. As with most of the cities we visited, the story of Pittsfield is one of deindustrialization. General Electric centered research and production of electric transformers in the city, providing great jobs of thousands of residents, but also PCB contamination of water and soil. (PCBs help keep oil from evaporating, making them useful cooling fluids for electric transformers. Unfortunately, they are also potent and persistent carcinogens.) Pittsfield is revitalizing as a cultural center, leveraging its position near music, dance and theater festivals in the Berkshires, and historical buildings like the Colonial Theater. But the contraction of industry leaves a major hole, and Pittsfield has been shrinking: the city’s ten Catholic churches have reorganized into four remaining congregations; the town’s mayors have encouraged development downtown, allowing neighborhood commercial centers to close down.

Part of the Detroit skyline

But understanding the basic dynamics of a shrinking city doesn’t make experiencing the shrinkage of a city like Detroit any less dramatic. Downtown Detroit looks like Manhattan, with streets as dark canyons between enormous buildings. But five minutes drive from the central city, you’ll find neighborhoods filled with vacant lots and decaying houses. The vacant lots are by design – they’re the product of an aggressive and succesful program to remove blighted buildings. From the 1970s through the 2000s, Detroit suffered from a particularly dark local tradition – Devil’s night – in which abandoned buildings were set on fire on the night of October 30th. In 1984, more than 800 fires “covered the entire city in an eerie, smoky haze on Halloween morning.” One of the best ways to prevent arson – and the possibility of death that comes with it – is to ensure there are no decrepit structures to burn.

According to Mike Evans, an expert on Detroit’s efforts to combat blight and creator of Motor City Mapping (a project to document land use and blight in the city), the city government took down more than 25,000 buildings between 1995 and 2014. Still, there’s visual evidence of the city’s shrinkage everywhere you go. We began thinking of blocks as having “missing teeth”, “rotten teeth” or “loose teeth”, a visual shorthand for their level of occupancy and upkeep. Hamtramck? Good teeth. Conant Gardens, where we went to look for J. Dilla’s childhood home? Loose, rotten and missing teeth.

Detail of ceiling of Dotty House, Heidelberg Project, Detroit, MI

In Detroit, loose teeth sometimes turn into something marvelous. The Heidelberg Project was artist Tyree Guyton’s response to the decay of his childhood neighborhood – with the help of his wife, grandfather, and eventually a group of international artists, he build a public art piece that was both protest and transformation. Houses on the street have been painted with polkadots and clock faces, and piles of discarded televisions, shopping carts, stuffed animals and other artifacts fill empty lots. While the project has been celebrated as a leading example of art for urban revitalization, it’s also been subject to “clearances” by Detroit authorities and through dozens of acts of arson. Guyton has stated his intention to disassemble the project, but it’s still drawing tourists like us to a neighborhood we likely would not have otherwise visited.

Part of Olayami Dabls’s African Bead Museum

For me, the most encouraging loose tooth transformation in Detroit is Olayami Dabls’s African Bead Museum in Petosky-Otsego. Since 1983, Dabls has been buying beads from traders who’ve come back from African trips, developing a remarkable collection of work from across the continent, with a particularly strong collection of West African beads. Dabls tells me that he began decorating his building and surrounding buildings with murals and fragments of mirrored glass as a way to attract attention to his project. The museum is now a bead shop whose proceeds fund Dabls’s art and the eventual construction of the museum building.

What’s most enticing to me about Detroit – and other legacy cities – is the ability to move from contemporary creativity to historic creativity. It’s a ten minute drive from the African Bead Museum to the Detroit Institute of Arts, one of the few museums where a Van Gogh self-portrait gets upstaged by the mural in the adjacent room. The mural is Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry, and it’s almost indescribable. It’s both an awestruck portrait of the industrial might of Detroit’s auto industry in the 1930s, and a howl of communist rage at the juxtaposition of worker solidarity and capitalist greed. Black, brown and white workers put sculpted shoulders to the wheel as frowning, suit-clad bosses monitor their every move. The two largest panels depict Ford’s then-non-union River Rouge plant, and it’s apparent that Rivera was following the march of unemployed workers to the factory gates, where six were killed by Ford’s notorious “service department”, a private army of gang members, ex-cops and ex-cons.

Five minutes drive from Rivera’s mural and you’re at the Piquette Avenue plant, where Ford Motors designed and hand-built the Model T. The Piquette was a static assembly plant – teams built the frame for the car on wooden sawhorses, and the engine – built by the Dodge Brothers in a nearby factory – was dropped into the chassis. These Model Ts were hand-painted and came in colors other than black; Ford’s famous quip about consumer choice came only after the company was producing millions of units a year, and evidently, black paint dried faster than all other colors. Understanding the transformation from hand-assembling a vehicle and driving it out of the factory to repeating the same task hundreds of times a day on an assembly line is critical context for Rivera’s mural.

High Falls, Rochester, NY. Photo from the roof of the Genesee Brew House.

These juxtapositions happened again and again on our trip. Rochester, the city we found most livable of the dozen cities we spent time in, featured both the history of photography embedded within George Eastman’s house, and the emergence of computer gaming in the remarkable Strong National Museum of Play, down the street from RIT’s acclaimed game design program. It’s not hard to find a line from the image on a glass plate to the image on an LED monitor, and it’s possible to see Rochester’s comparative recovery (down from 332,000 in the 1950s to 211,000 in 2020, up slightly from the previous decade) in that legacy of science and technology that is the city’s heritage.

Drinking a (non-alcoholic) Genesee beer on the roof of their brewhouse, overlooking the High Falls on the Genesee River, Amy and I found ourselves asking each other, “Why is this not the next Austin?” At a moment where climate change is making coastal cities vulnerable to flooding, southern cities swelter under extreme heat and western cities face persistent drought, the cities around the Great Lakes look pretty damned livable in the long term.

And yet, that’s not what’s happening. The fastest growing American cities are in waterlogged Florida, steamy Texas and rapidly drying Utah, while the cities we visited continue to shrink, or have recently bottomed out. Amy is from Houston, and she’s been looking into selling her condo, which has survived the last several hurricanes, but is across the street from properties that routinely flood. Miami routinely floods, filling streets with salt water and sewage, even on days when it doesn’t rain. (Predicted flooding from storm surges is much worse.) The Great Salt Lake is drying up, leading to toxic dust in Utah’s fast growing cities.

Factory, east side, Cleveland, OH

In the legacy cities of the Great Lakes, people are watching and waiting. In a haunting film – Freshwater – showing at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, dream hampton imagines Detroit filled with climate refugees from the rest of the country, coming north to return to the fresh waters of Lake Erie. But they’re not coming yet.

Somewhere between Detroit and Toledo, I started thinking about the question differently. Instead of wondering why legacy cities empty out while bidding wars have doubled housing prices in Austin in the past decade, I started to think about different worlds where different cities make sense. Between and just after the World Wars, Detroit, Cleveland and Buffalo looked like the good life to people around the country and around the world. Whether you were fleeing the Jim Crow South or looking for security outside of the turbulence in Europe, these cities promised you a steady job, your own house, a neighborhood surrounded by people who shared your culture, religion and language.

It was a vision of the good life that changed as the Cuyahoga caught fire, as Love Canal made parts of Niagara Falls uninhabitable, as steel mills and auto jobs moved south and overseas.

100th Street, Love Canal, Niagara Falls, NY

(We spent part of an afternoon walking around the Love Canal neighborhood of Niagara Falls. It was hard to know what was most disturbing: That there’s still half a dozen homes occupied within blocks of the dump site, an area where the ERA advises no one to live? That the toxic waste that seeped up into basements and street grates still exists, under a plastic sheet and a layer of topsoil? That the folks who have moved in just north of the contaminated neighborhood are the folks forced to the least expensive land – the local mosque in Niagara Falls is a block north of the contaminated area.)

The good life now celebrates software, biotech and finance. It unfolds in cities where universities produce startups and where venture capital supports ideas that become new industries. The employers who hire tens of thousands are in healthcare and insurance, not manufacturing. And these cities are no longer organized around factories. Instead, good life cities are warm year ’round (and often hot enough that they are uninhabitable without air conditioning.) Often they have walkable centers, but enough space that people have detached homes and cars for a half hour commute to work.

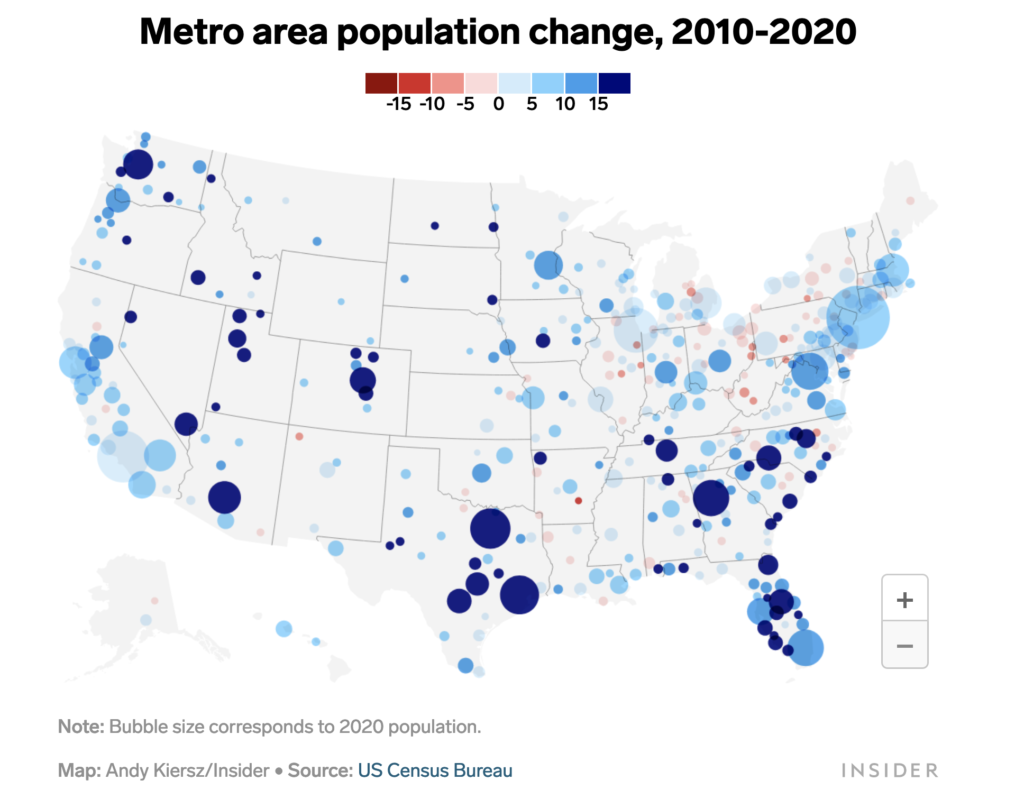

Map of expanding and contracting cities in the US, from Business Insider

But the good life is always changing. The pandemic sent many people to work from home, leading at least some people out of cities towards small towns and rural areas. At some point, rising interest rates will make it impossible for people to participate in housing bubbles, and shrinking cities might start gaining bargain hunters who can work remotely. Perhaps the California fires and Gulf Coast floods are the Love Canal of the age of climate change. More likely, they are just one of the dozen times the Cuyahoga caught fire, before the flaming river captured public imagination and outrage.

I truly believe that in a few decades we will see the shift of the American population south and west into deserts and flood zones as a sort of collective madness. But I’m self-aware enough to know that my love of the rural Northeast allows me to be smug about the environmental sustainability where I live, even as property values stagnate and my car gets stuck in snowbanks. East of Toledo, I find myself wondering whether we’ll visit Houston and Phoenix years in the future, marveling at wonders and destruction in turn.

Eve’s European Sweets, Syracuse, NY

In the meantime, the legacy cities of the Great Lakes are waiting. They’ve got room to grow, and space for the craziest of ideas. They already represent a better life for people from around the world, and they may once again house the good life of our collective future. They are as much our collective legacy as the National Parks and they’ve got vastly better food. And you don’t even need a camper van to come visit.

A lot of the software companies could be moved to Detroit and Cleveland and Pittsfield. They don’t *need* to be in SF or Austin!

(For that matter, I suspect a fair number of people would move, if they had the money to do so, and a guaranteed place to live.)

Great article! I took a 22K mile trip around the country in 2017 ( running away from DC and DJT.). Visited many of the cities you mention. As someone who grew up in Cleveland (wrong side of the tracks in Shaker Heights) it is especially poignant. Hope you are well.

Hi Ethan, Leetha Filderman from PopTech. It’s been a long time. I love your piece on Legacy Cities and I’m wondering if we might get you to venture to Washington, Dc for PopTech 2022 in October. I’d love to hear from you. Thank you for dropping me a note.

Ethan what a great synthesis of your travels! I often think that I don’t get enough time in my life to travel to all parts of this nation and I am most deficient in my exploration of the Great Lakes Region.

Thanks

Thank you for this. I’ve started thinking about where I might semi-retire to, since Nora can keep working from home regardless. I was looking at many of these cities, though I didn’t know that term. My only concern is the winter/snow. I have a colleague who retired early and moved high up in the Appalachian Mountains, so it’s never too hot, but never too cold.

I have a cousin in Syracuse whose mother-in-law runs a Polish bakery and restaurant that I think might be the one in the last photo. (I haven’t been, but all the aunts and uncles on my dad’s side of the family say it’s great.)

Anyway, as a lifelong Not-The-City New Yorker, I like seeing Syracuse and Rochester get some love.

Perhaps a readon so many are moving to Texas or Florida is to escape the decade uopn decades of over taxation and regulations of a hundred years of Democratic mayors and Govenors mismanaging socialistic experiments?

If you look at the areas hit hardest by the end of manufacturing, they were all in what was called the “trunk”, an area defined by the railroads and bankers who drove American industrialization. It was all run out of NYC, and, if it helps, think of it as an extended NYC colony or hinterland that ran west along what are now I-90 and I-80 and following the Great Lakes out to the land of winter wheat. A variety of forces ended it, but a big chunk of it was the interstate highway system that let one send goods of any type anywhere for the price of a truck and driver. The railroads set tariffs to enforce their vision of industrial America, but when their control ended, so ended a way of life. (I’ll suggest Nature’s Metropolis to get a feel for the development of the area much as an account of ancient Greek colonization of Sicily.)

Rochester is not surprising. It always had an educated work force. It wasn’t just Kodak. There were a number of high tech companies there including the largest manufacturer of traffic lights in the country. A friend of mine in college grew up in Rochester and said that they always had the most advanced traffic lights before they were available elsewhere. Rochester had the schools and training to match, so there was an educated work force. As weird as it sounds, universities have long kept cities alive in hard times. Look at what is now Ball State keeping Muncie alive through the Great Depression or Lehigh helping Bethlehem recover after losing the steel industry.

So many of the cities relied on a relatively uneducated work force. Factories needed strong bodies, not great minds. The technical talent needed was limited and it could be brought in from elsewhere. Maybe there is something like Jane Jacob’s theory of import replacement for an educated work force. A city with a suitable work force can develop and attract new industries and those industries can attract more people to the work force, but it is hard to build that kind of attractive center without an initial educated core.

Pingback: Vestigios obreros en la ciudad postindustrial – Socied@d Reticular

Pingback: Legacy Cities: an extended remix of my talk at PopTech 2022 - Ethan Zuckerman

Thank you & welcome home, Ethan, I’ve been reading your blog for many years. Born in Cleveland, grew up in Toledo, Pittsburgh & Buffalo, but drifted off from Illinois/Iowa to the southwest for ten years; now I’m back (in Galesburg). I’m glad to see the trees are still here, but the Mississippi is dry. Those who stayed have a strong spirit and will prevail. Meanwhile the southwest (we were in NM) is REALLY dry, to the point of being unsustainable. In the farm belt the problem is pesticides – when we figure out how destructive they are to our children, we’ll be horrified.

ðŸ‘ðŸ¼ðŸ‘ðŸ¼ðŸ‘🼠Hope you’re well Ethan and paths cross again one day! R

Excellent essay, and a memorable journey. Thanks for including the photos, too.

As a resident of the upper Midwest, I have to say I’d much rather live in a place where there’s snow (and lots to do outdoors in it so long as you wear warm clothes) than in a place where it’s too hot to be outdoors. That’s apart from the madness of moving to a place where climate change is trending toward uninhabitability and the political power is tightly gripped by people who don’t care.

Pingback: There’s no such thing as bad weather. There’s only bad gear. – Ramsay Inc.

Comments are closed.