I’d been warned that my laptop could be searched when I entered Zimbabwe. I correspond with a few folks in Zimbabwe regularly and had a few documents on the laptop – previous blogposts, primarily – that reference the nation. So I spent half an hour or so in the Johannesburg airport, putting potentially sensitive files into innocuously named folders: “Fred”, “family photos”, gzipping them into archives and encrypting the archives to myself with GPG. I renamed and refiled the encrypted files to look like they were part of system libraries, hid the USB key in a corner of the lining of one of my checked bags and concluded that this would probably protect me and my correspondents even if the laptop was seized, copied and inspected at leisure of Zimbabwean customs officials.

But then I started to worry about the newspapers I had with me. The Mail and Guardian – South Africa’s excellent newsweekly had a story about Chinese military advisors training the Zimbabwean military. Would that be seized? How about my copy of The Economist? (After all, this is a publication that once ran a story that began, more or less: “Robert Mugabe is a snappy dresser and an enthusiastic fan of cricket. That previous sentence is the only sentence in this article on Zimbabwe which could be published in that nation.”)

No one looked at my luggage as I entered Zimbabwe from South Africa. The procedure to obtain a visa didn’t involve a single form – just passing $30 USD across the desk to an official who entered my name and passport number into a notebook and handed me back a shining new Zim visa. (The immigration form does include two unusual questions – an inquiry about precisely how much cash I was carrying, and a query whether I or anyone in my family had ever been charged with a crime…) No security forces demanding my root password so they could copy my hard drive or wielding black markers to sanitize my newspapers. It was oddly disappointing.

(This is not to say that people aren’t searched when entering Zimbabwe, just that I’m not one of them. I suspect that if I were a known Zimbabwean activist, my movements would be followed more closely and my luggage checked more carefully.)

I was amazed to discover that both the Economist and the Mail and Guardian are available in Zimbabwean newsagents. However, they’re so expensive that they’re not read by the vast majority of Zimbabweans. This characterizes much of the situation regarding the press in Zimbabwe – it’s free for people who can afford it, and is little more than naked propoganda for those who can’t.

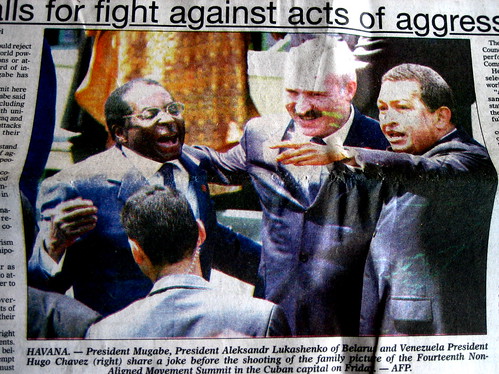

Broadcast television in Zimbabwe consists of a single channel, which alternates reruns of “The Golden Girls” with locally produced programs that include such hard-hitting programming as “Media Watch”, which consists of a gentleman in a suit reading headlines from government-owned newspapers. (One of my favorite headlines: “Mugabe blasts ‘Stupid Democracy'”. The accompanying photo features Mugabe, Lukashenko and Chavez sharing a laugh at the summit of non-aligned nations. Oh, to be a fly on the wall at that gathering.) You can see other programming in Zimbabwe via Multichoice DSTV (Digital Satellive TV, based in South Africa) – the Multichoice bundle includes CNN and BBC, both of which feature critical coverage of Zimbabwe. But it costs roughly $55 a month – paid in foreign currency – a huge sum for most Zimbabweans, and as a result, only a fraction more than 1% of Zimbabweans have access to this type of programming.

(That said, Multichoice can turn up in surprising places. Rashweat Mukundu, national director of MISA (Media Institute of Southern Africa) tells me that rural bars sometimes subscribe to Multichoice so they can broadcast football games. Because they’ve paid for the whole service, this sometimes means they’re watching CNN or SABC in the middle of the day…)

One reason Zimbabwe permits a small number of citizens to receive programming from Multichoice is that the operator pays the Zimbabwe Broadcast Holdings for the right to broadcast their programming to the rest of the continent – critically, these payments are in hard currency.

The situation with radio is a bit more complex. The Zimbabwean government has made it virtually impossible for private companies to enter the radio market. A group called “Capital Radio” applied for a broadcast license in 1999 and had their application denied – they appealed to the supreme court and won, but still not allowed to begin broadcasting. Since then, the regulations regarding media licensing have gotten yet more complex – foreign investment in media is controlled almost to the point of prohibition; owners of media companies can’t have more than 10% of the shares of the business, forcing companies to build large consortia of investors. And no independent stations have yet been licensed. (TVRadioWorld has an excellent list of radio stations in Zimbabwe. You’ll note that all the stations that actually broadcast are part of the national broadcaster, ZBC.)

The organizers of Capital Radio moved to London and reorganized as Shortwave Radio Africa, broadcasting into Zimbabwe from outside the nation. Unfortunately, they don’t have many correspondents in Zimbabwe, and shortwave radios are scarce, limiting their listener base. Reaching a wider audience is Studio 7, a US-government funded radio program produced by Voice of America. Broadcast from the US, via a repeater in Botswana, the program is available for two hours in the evening, and boasts a listenership of over a million. Friends involved with the project are proud that the station offers a range of voices, including individuals affiliated with the ruling ZANU-PF party as well as opposition figures. But they acknowledge that two hours a day isn’t enough to balance the 24 hour coverage on government stations.

The government evidently thinks that two hours of Studio 7 is plenty. There are many reports that the station is periodically jammed, allegedly with Chinese assistance. (Censorship is the sincerest form of flattery.)

A third alternative radio voice is the subject of an ongoing court battle. Voice of the People Radio has been producing radio content in Zimbabwe and sending it to the Netherlands, where it is transmitted via satellite to listeners throughout the southern hemisphere. Despite the fact that no transmission is taking place in Zimbabwe, the government has taken the founders of Voice of the People to court, alleging that they are illegally operating a radio station. My friend Isabella Matambanadzo is one of the ten defendants – she points out that the media ownership laws are designed to guarantee that a large set of people are required to take a risk to start a media venture, and that since those people are Zimbabwean, they are vulnerable to the sorts of charges she and her colleagues are now facing. Should they be convicted later this week, they’ll each face two years in prison for their alleged transgression.

The effect of suits like the case against VOP is to scare the heck out of anyone who might be tempted to engage in media broadcasting. But innovators are still testing boundaries. Unable to get a license for a community radio station, Radio Dialogue in Bulawayo is creating programming and disseminating it on cassette tapes, which they hand out to the drivers of minibuses. The bus drivers play the tapes on their runs, “narrowcasting” to their passengers and avoiding most reasonable definitions of broadcasting. Still, the reach is small and Radio Dialog like others would prefer to reach the airwaves, not just the highways; as their site puts it, “Radio Dialogue is a non-profit making community radio station aspiring to broadcast to the community of Bulawayo and surrounding areas.”

Zimbabwe’s most diverse media is the print media. This diversity reflects the history of media evolution in the state. Prior to Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, Zimbabwe’s broadcast media was controlled by the Rhodesian Front, and later the Rhodesian state. When Rhodesia became Zimbabwe, the state owned broadcaster moved from one state owner to another without becoming a public broadcaster.

But there had been competitive newspapers in Zimbabwe since the early 1900s, and that situation continued after independence. The new government received a six million dollar investment from Nigeria to allow the purchase of several newspapers and the regional affiliate of the Africa News Agency, but numerous other papers competed with those state-owned outlets. In early 1990s, publications like the Daily Gazette and the monthly magazine, Horizon, challenged official accounts of events, especially those of The Herald, the main government paper. In 1998, the Daily News – founded by the independent firm Associationed Newspapers of Zimbabwe – started challenging the Herald head on.

But the media environment in the late 1990s became increasingly difficult for independent papers. A proximate cause was Zimbabwe’s involvement in the DRCongo’s civil war – roughly 11,000 Zimbabwean soliders backed Laurent Kabila’s forces against the rebels supported by Uganda and Rwanda. The war was extremely unpopular in Zimbabwe – as one friend told me, “It was our Vietnam. We’ve got no cultural ties with DRC – we speak English, they speak French. We were colonized by different people. No one had any idea what we were doing there.”

What they were doing there had a great deal to do with financial deals between Kabila and Mugabe to reward certain Zimbabwean businesses with gold and diamond deals for the support during the war. Reporters covering these stories discovered that their efforts were often blocked by the Law and Order Maintenance Act, a 1960 law from pre-independence Rhodesia, which provides for the prosecution of journalists making statements which might cause “fear, alarm or despondency” in the country.

The irony of using a law passed by Ian Smith’s supporters to prevent ZANU-PF from accessing the press was not lost on Mugabe – ZANU-PF eventually replaced the law with a very similar bill, titled the Public Order and Security Bill. But no matter what the name, LOMA/POSB was a strong tool against independent journalism. In 1998, Ibbo Mandaza and Grace Kwinjeh of the Mirror were charged under LOMA for writing a story about a Zimbabwean solider, killed in the DRC, whose head was returned home without his body. The editor of the Standard, Mark Chavunduka and reporter Ray Choto were arrested and allegedly tortured for a story about an attempted military coup.

Attacks directly on papers discouraged independent journalists as well. The Daily News offices were firebombed four times in 2002 – the paper eventually retreated to South Africa. This has become a popular strategy for many figures in the Zimbabwean press – The Zimbabwean is written by authors in South Africa and the UK, printed in London and distributed in Zimbabwe, Botswana and South Africa. At least 10,000 copies a week come into Zimbabwe – because the paper is produced outside the nation, it would require a modification of trade regulations to prohibit its distribution.

Other “independent” weekly papers exist, though their degree of independence can be debated. The Financial Gazette, once one of the more critical papers, is now controlled by Gideon Gono, governor of Zimbabwe’s central bank. (Depending on who you ask, it may also be controlled by the CIO, Zimbabwe’s clandestine intelligence services.) But there’s no alternative daily paper, and with government control of the print, radio and TV, there’s little opportunity for the opposition to counter official accounts of events.

An example is the protest by the Zimbabwe Council of Trade Unions on September 13th. According to most media accounts in Zimbabwe, a small group of trade unionists were assembling for an illegal protest, and were dispersed by government forces – the official word implied that the protests were small, disorganized and evidence of the disarray of the ZCTU and the opposition MDC party. Foreign news reports focused on the mass arrests of participants and the brutal treatment of the organizers while in custody. Walking around Harare, rumors were spreading that the protests had been massive and succesful, closing off much of the south side of the city.

Who’s right? I don’t know. The foreign stories tend to skew towards painting the government as brutal and irresponsible; the domestic stories have factual gaps and sometimes don’t cover events at all; the rumors are rumors. Without the presence of outside journalists on the ground, it’s very hard for any events in Zimbabwe to avoid turning into Rashomon.

(A note – one of the most interesting and critical comments about the rally and the arrests comes from Mavis Makuni in the Financial Gazette. When my friend Dumisani Nyoni argues that there’s an independent press in Zimbabwe, these are the sorts of voices he’s pointing to.)

Many of the journalists who used to write from within Zimbabwe continue to write from outside the country on websites designed to report events from a critical perspective – New Zimbabwe and ZimDaily are two of the most prominent. These sites are accessible from within Zimbabwe – at least when the net’s turned on. But it’s only a limited set of Zimbabweans who can afford to access this information.

My activist friends in Zimbabwe are unanimous in their diagnosis of the media situation: Zimbabwe needs an independent daily newspaper and a radio station so that the general populus can get information critical of the government. They’re experimenting with alternatives – community newsletters printed on A4 paper, distributed in “high density suburbs” (townships) from person to person; news programs and activist songs distributed on CD and cassette.

But if they were suddenly given a license to broadcast or publish a paper, there would still be obstacles. The Zimbabwean economy is so fragile that there’s very little advertising support for papers. The history of harrassment, imprisonment and torture of journalists makes many writers fearful to report certain stories. Criminal libel law means that libel can carry jail time as well as fines, which helps prevent attacks on public figures. And the fact that journalists must be licensed and must renew their accreditation every two years helps keep pens down as well.

What’s really going on in Zimbabwe? I don’t know. Neither do you. And neither do most Zimbabweans, whether they live at home or abroad. Reading the BBC or CNN won’t help – they’re not on the ground here either. And like every other situation in Zimbabwe, it’s both better and worse than you’ve heard.

“Dancing Out of Tune”, a history of the media in Zimbabwe, written in 1999 by Richard Saunders as the companion to a film by Edwina Spicer is indispensible as background on the current press situation in Zimbabwe – unfortunately, it doesn’t seem to be available online. MISA Zimbabwe is an amazing resource for anyone interested in the Zimbabwean media. So is the Weekly Media Update produced by the Media Monitoring Project Zimbabwe – unfortunately, this resource is a bit hard to access at present due to the bandwidth restrictions the country is facing.

Mark Glaser from Mediashift has an excellent interview with independent Zimbabwean journalist Frank Chikowore, who I was lucky enough to meet with while in Harare – for media outside of Zimbabwe looking for a brave and smart correspondent in the country, Frank’s a great guy to start with.

Unsurprisingly, some of the best voices in Zimbabwe are the ones you can access online. Kubatana is a great place to start for news on the NGO community and general news on freedom of expression. Sokwanele and their blog This Is Zimbabwe provide a critical view of events on the ground. Zimpundit, who covers the country for Global Voices as well as maintaining her own site, is a must read. Eddie Cross is more than a little controversial, but is also very much worth reading.

This post is part of the Holiday in Harare series.

need more information on how the colonial governents in RHODESIA used control the media.

Comments are closed.