Pop!Tech 2006, the tenth anniversary of the conference, is titled “Dangerous Ideas”. I suspect you can characterize many of the ideas that come up at a conference like Pop!Tech as “dangerous”, if only because you can spend far too much time in contemplation of the topics that get covered here. You can participate in the danger as well – the conference is being streamed live, and you’re able to post questions online as well.

Brian Eno – musician, philosopher, perfumer, futurist and producer – leads the conference by taking on one of the most dangerous ideas – Darwinian evolution – quoting Daniel Dennett’s book title, “Darwin’s Dangerous Idea”. It’s so dangerous, he suggests, that it has not yet been assimilated into global consciousness. (He apologizes – this isn’t meant as an anti-American comment, which gets some laughs.)

The dangerous idea of Darwin’s is that simple things can give rise to the very complex. We tend to believe that humans – very complex things indeed – design things that are slightly simpler, like 747s and cathedrals. But evolution teaches us that it’s not an intelligence that dictates a reality, but a reality that creates intelligence.

This worldview leads us to realize that we’re no longer the privleged species in the web of life. As we understand the magnitude of the universe, we realize how small we actually are. As Hildegard van Bingham wrote, we are “a feather on the breath of god”. The magnitude of the universe should introduce some humility.

Understanding a fact like “a hundred trillion stars” is a complex act. You can grasp it intellectually, but that’s different from having a feeling about it. Humans act from intellectual constructions and from feelings. These feelings are not neccesarily articulated – often, they’re too complicated to articulate.

Eno offers climate change as an idea that’s hard to express in emotional form. We live in a beautiful world, utterly unique, as far as we know. just in the last 20-30 years, we’re starting to sense preciousness and ephemerality of the world we live in. This is very different from what the Victorians thought – the earth started on a date, is likely to finish on another date, probably very soon.

He offers a somewhat cryptic explanation of culture: “Culture is the way we look at ourselves, a place we create within which we can surrender.” Religion, he suggests, can do this as well – creating deliberately safe, nonthreatening spaces where we can try out other ways of being and feeling.

As an example, Eno offers Steve Reich’s piece of music, “It’s Gonna Rain”. The piece is a tape loop of an American preacher saying “It’s gonna rain”, over and over. THe piece involves two tape loops, played out of phase, intersecting in interesting ways. Eno remarks that it’s a piece made possible from the rise of multitrack recording, which was used by bands like Emerson, Lake and Palmer to layer countless instruments over one another. But Eno found this simple, elegant piece much more meaningful. It taught him that you don’t need much material and you don’t need much composing to make complex and beautiful music.

The art, Eno suggests, is actually going on in your head. “Cultural objects, art objects are things made by artists to give you the opportunity of creating something”

Displaying on the screen behind him is a piece of work titled “77 million paintings by Brian Eno.” The paintings are two images layered over one another, combined from source material in a way that will produce 77 million different paintings. Eno knows the ingredients and the algorithm, but not what it will actually produce. It’s “a piece of art that continues to make itself in your absence.”

Eno finishes by talking about a visit to the Exloratorium in 1978. (He offers an aside: much of the creativity of Silicon Valley comes from people visiting the Exploratorium and realizing how much they love science.) He mentions that John Conway’s “Game of Life” changed his thinking in a radical way. “Having watched it, you will never trust your intuition again.” Again, from very simple states and rules, amazing complexity results, in ways that’s hard for humans to understand.

Will Wright, designer of marvelous games like SimCity and the Sims, acknowledges the Game of Life as a seminal event for himself as well. He notes that Life is an amazing example of compression – a few bytes for pattern and rules make it possible to create amazingly complex simulations and animations. He runs us through some amazing Life examples – a computer based in Life, beautiful fluid patterns, etc.

Wright mentions that we’re the children of industrial mass production. We’re used to standardized artifacts, housing and media: some guys in a back room make a movie, and we consume it. But as children, we’re all creators – we all have design aspirations. Ask young children if they can dance, draw or sing and they’ll all tell you yes. Ask college students the same thing, they’ll all say no. “Education is teaching children what they can’t do.”

But some of us look for other ways to express ourselves – car customization, grafitti, computer customization. Even our artifacts are customized, with faceplates on mobile phones. But where we really have the opportunity to create and customize is online – he tells us that players in The Sims have created 100,000 pieces of furniture that individuals can download and add to their houses. There’s a wide quality range – lots of crap, some great stuff – but within that diversity, there’s some exciting creativity coming from users.

The trend in computer games is to build bigger and bigger systems with more programmers and content creators. Sim City was created with four programmers, one who worked on content, three on code. Now games involve a hundred developers, over half working on content. He offers logarithmic extrapolation – by 2050, it will take 2.5 million people to make a game and cost $500 million. So it makes sense that we need to find better ways for players to build the games with us.

To do this well, we need to understand how models work in games. We model the universe of our games by creating equations – in Sim City, crime = population density squared minus land value, minus police effect. Users play the games by making their own mental models of those rules. As we become better designers, we watch what users do and our games build models of those users, finding better ways to challenge and reward the users based on their behavior.

Wright’s new game, Spore, is based on the idea that users are creators and that we can populate universes with the creativity of different users. The goal, Wright says, is not to make the gamer Luke Skywalker, but to make her George Lucas, in control not only of the story, but of the universe as well.

As Steven Johnson described in a preview of the game, it’s inspired in part by Charles and Ray Eames “Power of Tens” films. It’s also sponsored by the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence and Drake’s equation – N = R fs fp ne fl fi fc L – an equation that predicts how many worlds in the universe might be populated.

Spore takes place in a universe which ranges from the very large to the very small and from the distant past to the distant future. Depending on where you are in the game, you experience it as a cell, an organism, a tribe, a city, or a civilization.

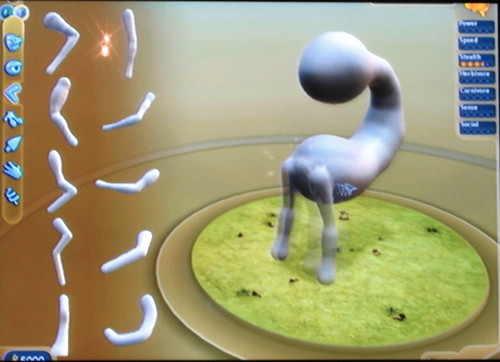

He walks us through the editors, which are the core of the game. We quickly create a creature shaped like a “C”, with a mouth at the bottom and eyes on the top. In about 20 mouseclicks, we get a creature which can walk around, do backflips, yell and spawn. As the creature starts walking around the world, it encounters other creates, all created by other players and loaded onto a main server. As Wright tries to forage for food, we die, prompting him to exclaim, “Life is hard.” We mate with another creature, lay eggs and defend them against scavengers – as they hatch, we gain evolution points, which give us a chance to buy improvements to our creature – faster feet, crueler claws.

As the game goes on, the creatures evolve towards intelligence and start building huts and then cities – again, all designed by players. As we reach interstellar intelligence, we build a spaceship that can roam our planet, collecting samples via the “abduction beam”. We can then bring these to other words and drop them off, where they can populate “empty” worlds or get killed by the indigenous species. In some cases, we can terraform the planets to make it more possible for species to survive.

In this stage of the game, part of the fun is collecting other species, which Spore treats as “trading cards”. You can bookmark the creator of those creatures and choose to bring her creations into your world.

Wright ends by showing us a “first-contact” scenario – we fly our spaceship over an alien planet and launch a fireworks show. The natives are impressed, and begin to worship us as gods. We abduct one of them – a trading card – and they open fire on us with lasers… As we pull out, we see ourselves in a small corner of the Milky Way, looking at trillions of stars, some computer created, some built by other players, in a way that brings the talk full circle.

Commenting on their interlocking talks, Wright and Eno offer a wide range of lovely soundbites. Eno distinguishes the creativity of pop music from “high art” by talking about creators and evolvers. A symphony has a single author, a whole vision, that gets articulated. Pop music, he argues, is the product of millions of people making incremental changes. That’s why “we don’t have the equivalent of cubism in pop music.”

Eno believes that there are sometimes whole groups of people who are engaging in creativity. He mentions that there were lots of contemporaries of Kandinsky making art almost as good as he did. He theorizes a brilliance of scenes – sceneius…

Wright talks about how hard it is to build a game that’s both an effective simulation and fun to play, admitting that Sim Earth was a terrible game. “We had all these options – for the player, it was like being put into the cockpit of a 747 in a nosedive.”

I get the sense that these guys could talk to each other for about a month, and I could listen to both for at least as long.

Pingback: PopTech streaming live « Scobleizer - Tech Geek Blogger

Pingback: The Marketing Excellence blog by Eric Kintz

Does anyone know of a place online to perhaps view the recording of this presentation?

I’d suggest watching the PopTech website to see when they put video of the presentations live…

Pingback: ADSENSERUSH - The last rush for adsensers. » Pop!Tech Presentation

Pingback: Open the Future

Comments are closed.