I’ve just spent eight days completely offline. I realize that’s not a very impressive figure – as I’m often reminding people, more than five billion people spend every day offline. But I’m not very good at taking vacations and even worse at taking vacations from the Internet, and that’s the longest I’ve been offline since 1998, when Rachel and I took a two-week honeymoon.

Driving back from Maine on Saturday night, I was listening to old episodes of This American Life. In an episode titled “Promised Land”, David Rakoff takes a 14-day liquids-only fast, hoping it will lead him to some sort of transcendent, religious experience – he’s disappointed when he discovers that he feels great, but hasn’t achieved transcendence.

My thoughts exactly. My expectations for a week offline weren’t as ambitious as Rakoff’s, but I’d hoped that freeing my mind from digital information might magically allow me to see my work from a different perspective, providing the clarity I lack on a day to day basis. Nope. But it felt great to break out of a routine for a week, to feel like I could start a day without email triage and the ritual removal of spam from the blog…

I spent a good part of the week enjoying old media. One of my favorite places in Maine is the Big Chicken Barn, an antique store housed in, you guessed it, a big chicken barn. The barn has an amazingly comprehensive collection of old American magazines, including near-complete runs of Time, Life, the Saturday Evening Post and others. I worked my way through piles of Time, looking for old airline ads, and found myself travelling through time through a wonderfully tangible, dust-smelling Wayback Machine.

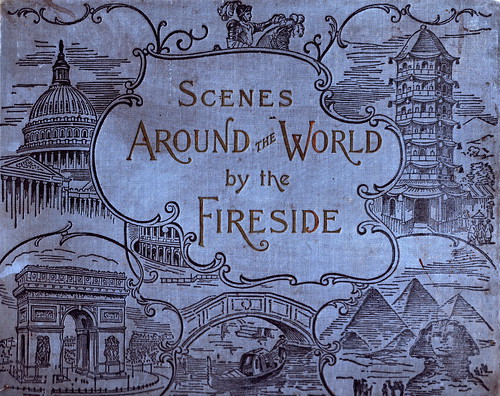

My best find of the week wasn’t at the chicken barn, but at a roadside tag sale somewhere west of Belfast. It’s a gem from 1892, a coffee table book given as a gift by E.W. Berry, a menswear store in Rockland, ME, to their customers. It’s a collection of photographs from around the world, famous buildings liberally augmented with portraits of European leaders, pictures of people in traditional dress and the occasional inexplicable collage of babies.

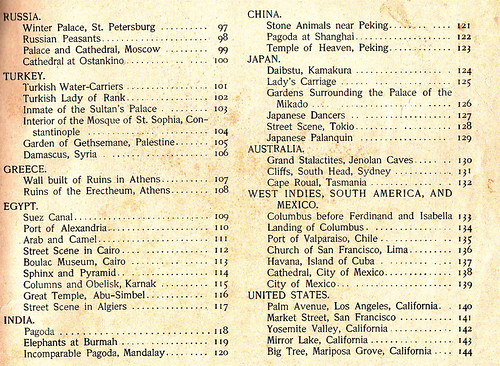

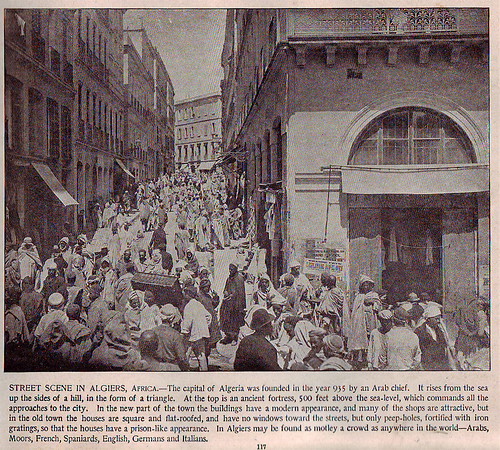

You’ll be unsurprised to discover that I was fascinated by the table of contents, trying to figure out the geographic distribution of the photos in the collection. There’s a heavy focus on Western Europe and North America, with nothing farther south on the African continent than Egypt. Some countries, like Turkey and Japan, feature multiple plates portraying the costumes of ordinary people and the wealthy – others feature nothing more than street scenes.

Rachel was fascinated by language in the preface of the book, which went to some lengths to defend the legitimacy of photography as a way of providing insight into the rest of the world:

The photographer’s camera makes no mistakes; it takes exact likeness. By the photo-type process, which has recently become very popular, the photo is transferred to copper plates and then printed. The beautiful views which render this volume a vast and charming picture-gallery are, therefore, exact reproductions of the famous originals. The eye looks at the object exacrly as it looked to the unerring camera.

No such accuracy could be obtained by engraving on wood or steel. From the whole grant outline down to the minutest details the reproduction is perfect, without any additions or omissions by the artist or engraver. The value of such copies must be apparent to every intelligent person.

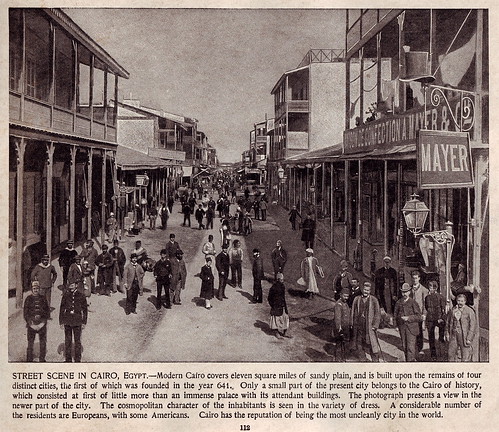

The occasional photo makes one wonder about the dedication to accuracy. My friend Daniel – who manipulates images for a living – points out that it’s hard to believe that all the figures in this Cairo “street scene” all happened to be facing the camera at the same time. A little work with a magnifying glass makes it very clear that most of the figures were pasted into the picture, and in a few cases, that faces were pasted onto bodies, using “the Photoshop of the times”. It’s pretty impressive work, nevertheless, given that each pasted figure needed its own handdrawn shadow as well…

It’s hard to imagine families gathering around an album of scenes from around the world and staring with fascination and wonder… though that’s precisely what my family did for almost an hour when I brought the book home. We spent a good deal of time wondering who the audience for the book was – educated people who hadn’t had the chance to travel to Europe, but felt like their education demanded a knowledge of the Continent? Working people who’d likely never travel beyond their home states, giving them a chance to see more of the world than they’d otherwise ever see.

With four of us crowded around the kitchen table of the house we’d rented in Maine, we’d collectively seen roughly half the places depicted in the book – with the exception of myself, my family isn’t unusually well-travelled. It’s just become vastly easier – and vastly more common – for the average American to see the Alhambra or the Pyramids at Giza than it was for the book’s owner 115 years ago.

I wonder sometimes if the possibility of travel, and the ability to “visit” places through much richer media than black and white photographs limits our interest in seeing those places. In the 1980s and 90s, Rick Smolan and collaborators created a series of books that documented daily life in America, the Soviet Union, and then eventually different corners of the world, including the wonderfully dated “24 Hours in Cyberspace“, assembled in 1996.

A decade after Smolan’s cyber-project, you can see photos from Ghana or television from Thailand with a mouse click. But it’s hard to believe that looking into another country or another culture would have the same appeal that staring at these prints 115 years ago might have had for a small-town boy in Maine.

I am glad you are back on line. I can see you had good time. I guess I am college student now–wondering in the beautiful Brandeis campus.

It is very amazing how real world and College are different. I still can understand why human created this great system where people go to learn about them self. I think they call it College?

Comments are closed.