Yesterday was election day here in the US, and was interesting to see how much like a holiday my colleagues (and I) are treating it. Roughly one third of my colleagues wore Obama shirts – there’s a surprising absence of McCain/Palin gear.

We celebrated our non-holiday (because, oddly enough, election day isn’t a day off for most people, even if polling places are experiencing multiple-hour waits) with a lunch talk by Professor Sunshine Hillygus, political science professor at Harvard and author of “The Persuadable Voter“. Her talk, “Divisive Technology: The Impact of Information Technology on Presidential Campaigning”, focused on the ways in which politicians are using technology to “microtarget” voters and deliver specific messages to specific voters… and what this might mean for (American, mostly) democracy. A timely subject, to say the least.

Professor Hillygus argues that the new information environment – a world of 24 hour news cycles, electronic communication and database marketing – has changed who politicians talk to and what they’re willing to say. The change isn’t just about style – it’s also about substance. These changes go beyond what we’ve expected to see with the rise of blogs – an increased engagement in political debate for those who are already interested and widening gaps in political knowledge for those who aren’t.

Hillygus argues that the ability to microtarget voters, selecting small subsets from databases via questions asked in polling and by cross-checking lists against databases of magazine subscriptions, changes political speech. Candidates are willing and able to take many more stances on issues than they’d take in broadcast media like television. Her research saw major-party presidential candidates in 2004 taking positions on 75 discrete issues in direct mail and email, vastly more issues than either addressed in television ads, speeches or interviews.

The goal of microtargetting, she argues, is not reaching undecided voters. Those guys are unpredictable and unlikely to vote anyway. The goal is to reach persuadable voters. These are voters who may not be aligned with your party, but may align with your candidate on a key issue: a persuadable partisan. This might be a Republican who’s pro-choice. If you can convince that person that an election is about abortion, s/he might be willing to cross party lines and support your candidate. “The goal is to build a coalition between the base and persuadable voters.”

You’re looking “to create cleavages in the opposition”. This can be done by narrowcasting messages to individual voters on issues you think will cause them to break away from their party, which they usually align with based on economic issues. You’re looking for a wedge issue, like gay marriage or abortion. Of the candidate-paid direct mail Hillygus analyzed, 30% focused on wedge issues, and 9% on “moral wedge issues”, as compared to 0% in

television ads.

This targeted campaigning is so effective because it allows the candidate to speak to an audience in terms they’ll understand, but which might not play well on a broader stag. “It’s dog-whsitle politics – you’re sending messages to those you intend without letting anyone else know.” These messages are heavily targeted to active voters in competitive states – this reflects the need to intelligently allocate resources, to people likely to vote and likely to have their vote matter.

She sees this trend as being potentially very damaging to our political life. People may be being “peeled away” based on trivial issues, like which candidate is more pro-snowmobile. (Oddly, this was pretty easy to figure out in the 2008 election.) It’s being used because it works – people are more likely to disagree on social issues than economic ones, she argues. But it’s not clear whether this pattern will hold as clearly in the 2008 elections, in part because Obama is taking a very different approach, targetting people who don’t have a high history of voting participation and attempting to create new voters, instead of persuading existing ones.

I found myself trying to digest Hillygus’s talk in the wake of Bill Bishop’s The Big Sort. I finished reading the book a couple of weeks ago, and I’ve been carrying it around with me, trying to figure out whether to review it or not. There’s much in the book to like – a smart, insightful analysis of American political and social history and a provocative thesis. And there’s much not to like – a thesis that’s supported more via anecdote and history than data, and which ultimately paints an extremely stark picture of American political life.

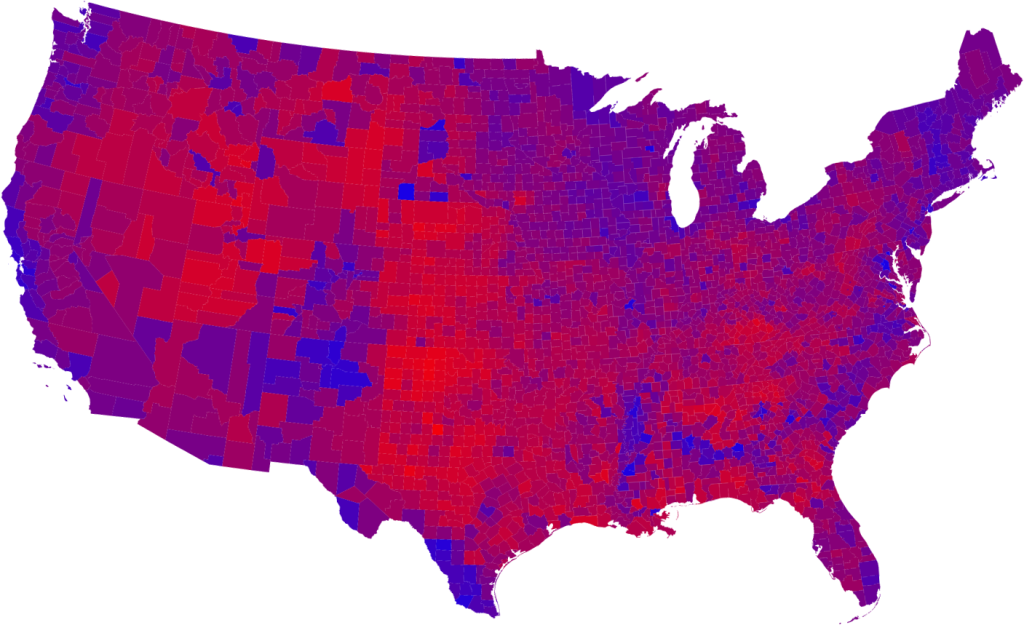

Bishop argues that Americans are creating ideologically homogenous communities by physically relocating, sorting ourselves into churches and neighborhoods that minimize our contact with the “other” and maximize interaction with those we’ve got ideological and demographic common ground with. He offers a statistical argument based on the rise of “landslide counties”, counties where a presidential candidate wins by more than 20% – he sees a sharp rise in the number of these counties between 1976 and now, and argues that the distribution can’t be explained by gerrymandering.

He offers an explanation of our polarization based on a split of the church into a more liberal branch focused on social issues and a more conservative branch focused on personal salvation. And he traces the rise of megachurches and their use of recruitment techniques which sort new converts into small groups where they interact with people who are very close in age and background. This comfort of the group, writ large, is what we’re looking for when we move… and as Americans are very, very mobile, we’re rapidly sorting ourselves into a red and blue nation.

Okay, so some of this rings true. I’m doing a lot of reading on homophily, and there’s certainly strong evidence that humans will sort themselves into homogenous groups around the smallest differences. It makes sense that we’d gravitate towards people “like” us. And I remember, four years ago, bemoaning the fact that I literally didn’t know anyone who was planning on voting for Bush, and therefore was blindsided by election results. I certainly live in an area that’s politically segregated.

But the red/blue dichotomy proposed by Bishop seems a little too simple to me. Are union steelworkers in Pittsburgh – reliably democratic – the same group as my college professor and dairy farmer neighbors (also both reliably democratic, though probably a mistake to put them in the same category, either)? Professor James Gimpel’s patchwork nation theory seems a lot more nuanced and closer to the reality I’ve observed on the ground.

The patchwork nation – the idea that the US is more complex than red and blue, and likely is better explained by roughly a dozen more complex demographic categories – leaves a bit more room for Hillygus’s theories as well. If we’ve sorted ourselves into red and blue, and we’re looking to our neighbors for cues as how to vote, how persuadable are we really? On the other hand, if we’re living in an “immigration nation” community, it’s possible that we might be pushed to the right with a strong wedge appeal on abortion, or to the left with a strong appeal for immigration reform.

I’d been hoping that Obama would win so decisively that I could simply dismiss Bishop with evidence that there’s democratic support virtually everywhere. But, of course, a “landslide” in American politics means getting 53% of the vote, not 60% or greater. And there’s no doubt that there are communities where people voted very heavily for one candidate or another.

Map by Mark Newman, licensed under creative commons. I.e., spread it around…

But there’s a lot of purple on this map as well. Perhaps this is because we’re not as well sorted as we will be in a few more years, when we simply can’t speak to each other at all. Or maybe we’re more persuadable and less fixed than Bishop thinks we are.

I’d like to think this last conclusion is the case. Like many Democrats, I’ve taken heart at the stories I’ve heard of long-time Republicans crossing party lines to vote for Obama, either from a desire to be “on the right side of history”, to punish Bush, or for fear that the McCain of 2008 wasn’t the principled maverick of the McCain of 2000. But reality forces me to admit that Obama’s victory has more to do with the turnout of Latino and Black voters, and of some new, younger voters, not hundreds of thousands of voters crossing party lines.

Is Bishop right? I hope not. He’s got very little hope for a post-partisan nation. And the most exciting thing about the Obama victory for me was the fact that he ran a 50-state campaign and shows a genuine commitment to try to lead the whole country, not just the blue states.

Is Hillygus right? It’s hard for me to say, at least in the 2008 election. Ultimately, wedge issues may have mattered less than the simple economic truths that faced Americans after eight years of unsuccessful policies. The passage of Proposition 8 – illegalizing gay marriage in deeply Democratic California – is a reminder that economic and social policy don’t always go hand in hand.

What I do know is that I’m deeply proud that Americans – white and black, red and blue – managed to elect someone who has a vision of America that’s less about subdivision and microtargetting and more about common ground. Yep, I’m realistic – I understand that “Barack Obama does not fart cinnamon-scented rainbows. He is not trailed by angels and unicorns.” I expect to be disappointed more than once, and to disagree with Obama’s compromises in more than a few cases. But I’m thrilled, not just that we’ve demonstrated that a nation stained by the history slavery can elect a man of color to the highest office in the land… but that he’s committed to a style of government that tries to represent all of us, not just those of us who moved to blue neighborhoods to support him.

Pingback: cyrusfarivar.com » Blog Archive » » We’re more purple than we think

Comments are closed.