This story is cross-posted on FOLD.cm, where it’s got more links, images and a layout that lets you see what’s behind the links while you read the story. Check it out there, and try FOLD to publish your own stories.

I became a Anthony Bourdain fan when he moved from the printed page to the television screen. I’d enjoyed his snarky, insider view of the NY restaurant scene, but I identified more with his mix of wide-eyed wonder and frustration as he began traveling the world in search of inspiring food and the people and cultures behind it. As his traveling circus has moved from network to network, he and his crew have gotten braver, focusing less on strange food and more on the politics of the places they’re visiting. In his show on Myanmar, the first interview is in one of Yangon’s ubiquitous tea shops. But the interview is with a leading opposition journalist, not a chef or food writer. Bourdain still eats well, but his viewers leave with an impression of a city’s character and politics, not just its flavor profile.

When Bourdain and “Parts Unknown” came to Massachusetts last winter, I was excited. Everyone comes to Boston, but very few TV crews make it out west past 495, the conceptual dividing line between Boston’s suburbs and the rest of the state. One of the promotional shots for the show featured The People’s Pint, one of my favorite bars, in Greenfield MA. So Rachel and I sat down to watch the show a few days before last Christmas, fingers crossed that our friends with restaurants in western MA would be showcased in front of an international audience. And then discovered that the show wasn’t about food, but about heroin.

Bourdain learned to cook in the clam shacks of Provincetown, MA, and the show follows him through the streets of the charming seaport, as he remembers his wild youth and his introduction to drugs, and eventually to heroin. To examine what heroin is doing today, Bourdain visits Franklin County, MA, a corner of western MA that’s wrestling with an opioid epidemic. As Bourdain interviews a former heroin dealer while sitting on a log in the woods, my hopes for seeing favorite restaurants like Hope and Olive featured turned into a fervent prayer that I wouldn’t see anyone I recognized.

Western MA and southern Vermont have become major transit points for heroin moving north from New York City along I-87, I-89 and I-91. Some of it heads to Boston, Portland and Montreal, but enough sticks around to saturate small towns. Some heroin users have never used another illegal drug previously – they got hooked on pharmaceutical opioids prescribed by doctors treating pain and turned to heroin when pharmacies became more careful about releasing Oxycontin and other prescription medications. Others are kids bored with small town life, long winters and collapsing economies. Towns like Bennington, VT – featured by the New York Times in a story about the rural “heroin scourge” – have small police departments that are desperately trying to catch up with the reality of a local drug trade.

There’s a possible upside to the opioid epidemic, if it’s possible to say such a thing about a tragedy that’s destroying families and killing people. A rural, white drug epidemic might be what finally ends the US’s racist, failed war on drugs.

A recent New York Times article featured Leonard Campanello, the police chief of Gloucester, MA, a beach town north of Boston, praising his approach to heroin, which keeps addicts out of prison and steers them into treatment programs, locally and nationally. His program, which has inspired dozens of others around the country, is laudable, as are efforts by Vermont governor Peter Shumlin, who spent the entirety of his 2014 State of the State message talking about opioids, seeking to reframe the conversation about heroin as one about public health, not about crime. Police officers in our area carry Naloxone, a drug that can often reverse heroin overdoses. Some police departments have unofficial policies that heroin users won’t be arrested, particularly if they are bringing in another user who is overdosing.

In other words, in our corner of New England, we’re starting to see a sane, rational, humane approach by law enforcement to drug addiction. We’re starting to see people realize that drug addiction is a health issue, that prosecuting end users is counterproductive, that treatment is vastly less expensive than incarceration.

It’s about time. And all it took was for our neighbors to become addicts.

The war on drugs has disproportionately been a war on black people. African Americans are 12% of the population of US drug users, but represent 38% of those arrested for drug offenses and 59% of those in prison for drug offenses. These numbers didn’t happen by accident – the war on drugs is one of the clearest illustrations of structural racism in action. Mandatory minimum sentences initially prescribed sentences for crack cocaine (disproportionately used by African Americans) at 100 times the severity of sentences for powdered cocaine (disproportionately used by white Americans) – 10 grams of crack led to the same sentence as 1kg of powder, despite the fact that the two are pharmacologically identical. Sentencing reform dropped this disparity to 18 to 1 in 2010, but harsh sentences aren’t the only reason for disparities in prison populations. Overpolicing of communities of color is another reason. Lots of cops on the street lead to lots of arrests for petty drug crimes, which means more people have previous offenses, which means future arrests for minor drug crimes lead to serious time.

So when white police officers suddenly realize that the war on drugs isn’t working because white people are dying, it’s easy to understand why people of color might find these displays of compassion somewhat frustrating.

It’s astounding how easy it is for law enforcement to have compassion for white drug addicts. https://t.co/slrssP6Sfp

— Lydia Polgreen (@lpolgreen) January 24, 2016

My guess is that the shift in law enforcement attitudes isn’t purely racial, but also tribal. The communities where these policy changes are taking place are often small towns where police officers are literally arresting neighbors and their kids. Mayors and police chiefs in these towns talk about how difficult it was to arrest their kid’s childhood friend or classmate. My guess is that the realization that your child could be next – a realization that comes from seeing a problem as one that affects your tribe – goes a long way towards building compassion.

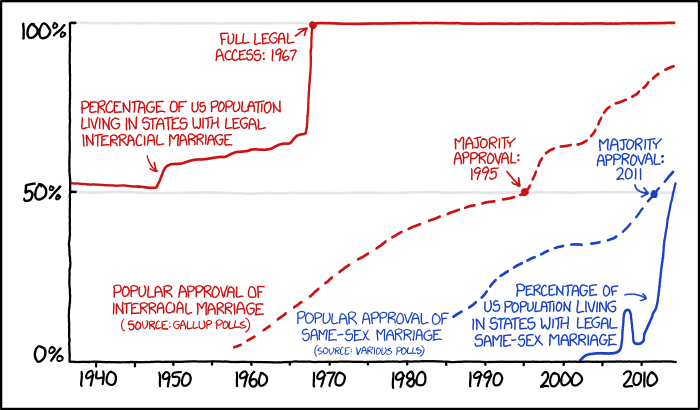

In this sense, we may be seeing a moment with drug abuse in the US that’s not unlike a national shift around equal marriage for gay and lesbian couples. For civil rights advocates, the incredible speed at which a majority of Americans accepted equal marriage stands in sharp contrast to the centuries-long struggle for the legalization of interracial marriage. One theory that has been offered for the difference in pace is that gays and lesbians appear to be evenly distributed throughout the US population, which means that most families – even Dick Cheney’s – have a homosexual somewhere in their family tree, while interracial marriage in a majority white country is disproportionately common in communities of color. Perhaps the discovery that drug addiction affects white and black, rural and urban is what we need to finally turn our national discourse on drugs from one about crime into one about health.

My hope for this moment in time is that families who’ve gone through the trauma of losing a loved one to opioid overdose will see themselves as part of a national movement to reform our nation’s broken drug policies. My hope is that the police chiefs and political leaders who are helping Vermont and Massachusetts cope with heroin abuse will help colleagues throughout the country realize that the drug war is a destructive and broken strategy. And my hope is that the sense of “we’re in this together” that communities are manifesting in response to the opioid epidemic is one that could extend beyond rural white communities and represent a new approach to tackling not just drug addiction but problems of poverty, health, and structural racism.

Hope alone won’t make change. But hope, in tandem with anger at the unfairness of a drug war that has decimated communities and ruined lives, might be enough to finally end the war on drug users and build a compassionate response to addiction.

Much progress has been made, as you’ve noted, in helping people who are addicted to opiate drugs get the help they need to put an end to their drug use. Even those who are high-functioning addicts have a need for treatment for their health issue.

Comments are closed.