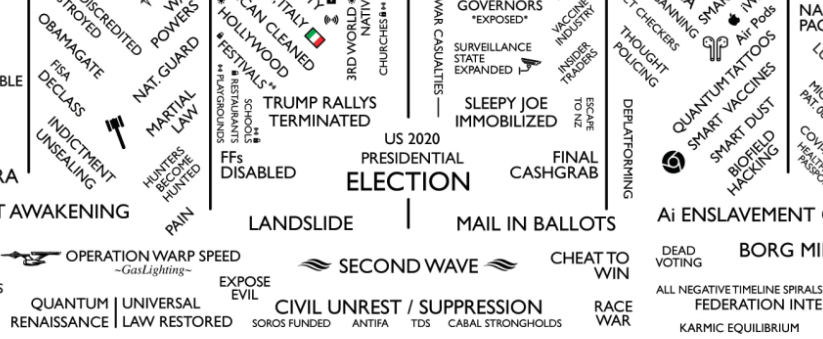

I’m quoted today in an excellent article by Jose Del Real in the Washington Post. The article addresses the ongoing challenges we are likely to face as a nation as we cope with the aftermath of a president and an administration actively at war with the truth. It is unlikely that alternate reality conspiracy theories like QAnon will evaporate simply because Trump has lost an election – indeed, the power of the “stop the steal” narrative to drive attacks on the Capitol should give us pause about the dangerous forces unleashed when large numbers of public figures embrace narratives that are simply not true.

Jose’s an excellent reporter and does WAY more work than the minimum you’d need to publish a piece like this. What that means is that hours of conversations turn into a quote or two in an article. But in this case, I happen to have an email that I sent, responding to Jose’s question about how people can be prevented from falling into disinformation bubbles like QAnon. Here’s what I wrote in response. (I’ve added hyperlinks for the blog post that were not in the email.)

Jose, that’s a massive question that no one has found an adequate solution to.

It’s worth noting that it’s not an internet question so much as it is a media and education question. There was a horrific wave of disinformation that led to the English Civil War in the mid-1640s – historians now point to Charles I losing control of the presses in London. A wave of anti-Catholic pamphlets rife with misinformation led eventually to Charles’ execution, his son’s exile and the rule of England under Cromwell and Parliament. In the long run, it also led to the establishment of the Royal Society, whose motto “Nullus in Verba” translates roughly as “Take no one’s word for it”, an explicit warning against the dangers of disinformation. This is not a new problem.

We know that it’s possible to recover from waves of disinformation because we’ve done it before. One thing that helps is when media and political authorities stop amplifying misinformation and support the consensus reality. Erick Trickey wrote a good piece in WaPo yesterday arguing that the paranoid and conspiracy-mongering John Birch Society (which led Hofstader to write “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”!) was dethroned by William Buckley’s fierce attacks on them in the National Review and Reagan’s refusal to accept their support.

The parallel here: if Fox News and major republican leaders stopped supporting conspiracy theories, perhaps we could reduce their spread and decenter them from the heart of the Republican party. Reagan and Buckley didn’t attack the media systems that were spreading Bircher propaganda (much of which moved through the mail, through magazines and through word of mouth) – they renounced the politics from the positions of power in their respective institutions.

There have been countless fact-checking and other efforts designed to rid social media of misinformation. They’re not going to work until the party and the major ideological amplifiers start explicitly renouncing these points of view. The signs are not good – while Fox News was willing to declare that Joe Biden had won the election, they are still providing platforms for people denying the facts of the victory. And a majority of Republican representatives voted to overturn a democratic election. Until there are consequences for perpetuating those falsehoods, don’t count on changes to the media to solve this problem.

It was those last two sentences Jose chose to close the piece, and I’m glad he did. I am increasingly convinced that we’re looking in the wrong places to solve our problems of information disorder. I’m less convinced that this is a problem of information systems and increasingly convinced that this is a problem of power and responsibility.

Obviously, I believe that information is important: that’s why I became a communications scholar comparatively late in life. I am grateful for the work of brilliant colleagues – Joan Donovan, Renee DiResta, Kate Starbird, Claire Wardle, Julia Ebner and so many others – who are working to document and understand the spread of mis and disinformation from distant corners of the internet into mainstream media dialog. Thus far, I’ve found the model that Yochai Benkler and his collaborators outline in Network Propaganda the best frame for understanding how disinformation gets normalized, but I worry that it places too much blame on media organizations like CNN and the New York Times and not enough on those in positions of political power who benefit from disinformation.

Blaming social media is too easy an explanation for the terrible situation we collectively find ourselves in as a nation. According to polling this week, 7 in 10 Republicans believe Biden was not legitimately elected. For many Republican politicians, there is little incentive to challenge this false narrative: due to gerrymandering, winning their primary is equivalent to winning re-election, and no one wants to alienate 70% of their voters. Whether we “fix” Facebook or YouTube, whether or not we deplatform more QAnon folk or drive militia members into encrypted chat spaces, two more years of elected leaders repeating disinformation is going to hurt us as a society.

It is not clear that Trump’s departure from the White House will be a departure from the political stage. So long as he threatens a run in 2024, media outlets will feel compelled to report on his words and thoughts. Ignoring a former president is hard for news outlets to do – ignoring a candidate for president in 2024 is virtually impossible. One of the many fears I am nursing at the moment is that no one will emerge to tell Republicans that they need to abandon the obvious mistruths around Trump’s defeat and become full partners in governing a nation that’s going through a very rough patch.

In other words, I think we’re trying to fix social media in part because it’s too hard and too scary to fix our political system. The problem is that even if we build better, more thoughtful, more careful media systems – as I thoroughly believe we should do – they may not be able to help us through a moment where many of our leaders embrace a demonstrably false narrative. This creates an impossible dillema for news media: report on what Republican leaders say and amplify disinformation, or agree not to report on some substantial percentage of our elected representatives.

I do not mean to minimize the problem of political disinformation. I think there are serious vulnerabilities with existing media systems, including the tendency to amplify the most angry and passionate voices over those seeking common ground and concilliation. I worry thought that our fascination with shiny new problems – deep fakes, QAnon, social media echo chambers and algorithmic influence – is pulling us away from basic and fundamental political problems that we are a long way from solving.

Ethan,

We have a number of acquaintances in common. Darshan Goux at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences as been a colleague of mine since the early 90s. Your fellow Democracy Commission members Dee Davis and Carolyn Lukensmeyer are friends and fellow collaborators. I’m launching a WikiWisdom Forum to celebrate Danielle Allen’s Kluge Prize on Thursday.

I’m working quietly with a US Senate office on linking the disinformation consumption fee idea I outlined last summer in the San Jose Mercury with a new national civics effort.

Would you be willing to talk sometime after the Inauguration about this and a few other ideas I’m working on?

Thanks

Tom Cosgrove

Co-Creator of the film Divided We Fall: Unity Without Tragedy

Boulder, CO

617-529-1170

Isn’t the solution to the impossible dilemma to report on what Republicans say while framing and explaining that their words are disinformation?

I have thought for along time that the willingness to lie to get votes ect… is the main problem. When people in power are more afraid of losing power then of being honest, we have a serious problem. I do think Mitt Romney said it best . The best way to solve this problem is to tell the truth to your voters! It would go along way to tamping down on these conspiracy problems.

Pingback: “In other words, I think we’re trying to fix social media in part because it’s too hard and too scary to fix our political system” – “Fixing disinformation won’t save us” by @EthanZ – dropsafe

Pingback: Even when social media may remove disinformation, it will not repair the issue | Boing Boing - Zbout

Pingback: New Fixing disinformation won’t save us – Stephen's Lighthouse

Just seeing this now and wanting to say that I totally agree. You’ve squared a circle for me. Because we have had serious disinformation problems many times before we had new media (though Colin Powell did use Powerpoint in his infamous presentation to the Security Council), and when political leaders choose to lie and try to change reality to suit their agenda, that’s the deeper problem.

That said, I also worry that the way political and civic action gets funded today distorts what problems get attended to. A great deal of the work underway now on what you refer to as the “shiny new problems – deep fakes, QAnon, social media echo chambers and algorithmic influence” is work that foundations and other c3 oriented donors can fund. Whereas challenging a political party that has embraced misinformation as a core principle isn’t something foundations can tackle.

This is spot on in noting that disinformation is not new with the internet, much less the web. But it is a huge leap to say that the waves of disinformation in the 1600s _led to_ the English Civil War. The relationship was much more complex, but also points to the limitations of attempting to control technology through regulation and underscores the main point of the article that regulation of technology will not just fix disinformation or its relation to society. It is true that pamphleting blossomed during the few years that licensing was not in force during the 17th century, but the interrelation of Stationers’ Company registration and state licensing was complex and both were very unevenly enforced when they were in place, often intentionally. Disinformation, novel technology, and attempts to control it through both regulation and proprietary policy were a large part of what was taking place, but it is very misleading to make such simple assertions about the causal relations and directions.

Comments are closed.