My great aunt Jean carried a huge plastic tote bag as her purse. On each side of the bag were photos of eight of her grandchildren, surrounding a photo of a bottle of dish soap on one side, and of laundry detergent on the other side. “See?” she’d say, “They’re my pride and joy!” (Get it? Jean would check to be sure you got it.)

This cheap, plastic sword is one of my most prized possessions. It has five signatures on it, the five students I’ve awarded PhDs to for their work at Center for Civic Media at the MIT Media Lab.

It’s part of a tradition that I started as a joke. As Nathan Matias was preparing for his PhD defense, I saw a photo of Finnish PhD students being awarded top hats and swords to recognize their achievement as defenders of the truth. I decided it would be nice to have a similar tradition at MIT, but felt that perhaps students would need to earn those swords. So I appeared at Nathan’s PhD defense with two plastic swords. When the committee met to evaluate his dissertation defense, I asked all committee members to sign the sword. I then presented him with it and attacked him with my own sword… to his great surprise!

He defeated me in single combat and started the Center for Civic Media tradition that a PhD defense should be a literal defense. Erhardt Graeff took the tradition to the next level, scripting a battle with me ala The Princess Bride, in which we both began our sparring match left-handed and switched to our dominant hands. Jia Zhang opted out of the tradition in a distinctive way. Upon being presented with her sword, she simply stabbed me in the ribs with it, ending the match.

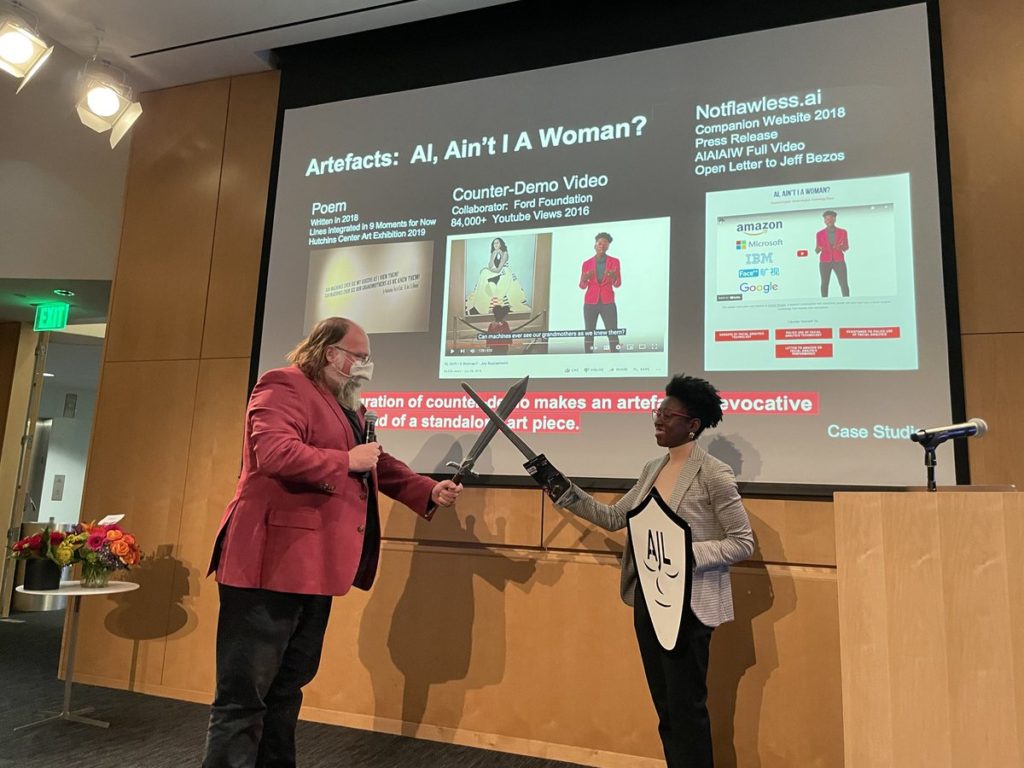

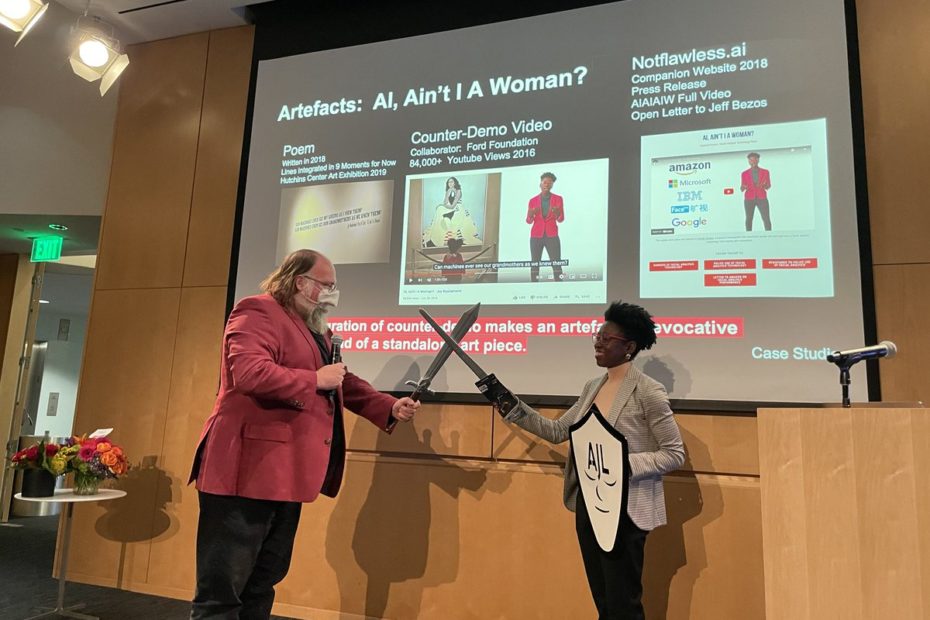

After I left MIT in 2020, it wasn’t clear what we should do with the tradition. Joy Buolamwini and Alexis Hope, both defending this season, suggested that the tradition might need to alter to recognize the fact that A) we are in a different stage of our work as a lab, and B) it’s not necessarily fun to have a 300 pound man charge at you with a plastic sword in front of friends and family on one of the most stressful days of your life. We’ve now adapted the ritual for a post-MIT context. The defending student is presented with her sword, she and I bow to one another, cross swords, tap each other on the shoulder, and hug. That’s what Dr. Joy Buolamwini did last night at the end of her brilliant defense.

Joy’s work has gotten a great deal of attention through extensive news coverage and a documentary, The Coded Gaze, that builds on her research on algorithmic bias in computer vision systems to examine the broader space of ways in which biases can be built into algorithmic systems. It would have been pretty easy for Joy to have built a dissertation purely around that work begun while she was a Master’s student, but is still generating new research papers, congressional hearings, and numerous follow on audit studies. Instead, she did something different and very brave. Her dissertation examined the idea of an evocative audit.

An evocative audit is designed to complement an algorithmic audit. An algorithmic audit is conducted scientifically, dispassionately, and carefully, and evaluates the ways in which an algorithmic system succeeds or fails in different test cases. Joy’s work with Timnit Gebru, analyzing computer vision systems to demonstrate that they failed disproportionately often on black women’s faces is a classic algorithmic audit, and algorithmic auditing has now become an important and growing field as we seek to understand the power of algorithms in our lives and hold them responsible.

But the reason Joy’s algorithmic audit is so well known is the evocative audit she paired it with. Joy’s most famous demonstration, a counter demo that she calls it, is one in which she sits in front of a computer vision system that sees a lighter skin woman’s face perfectly, but fails to recognize her face. When Joy puts on a featureless, white mask, the system recognizes her immediately. This failure and the emotions it generates is the heart of the evocative audit. Unlike the algorithmic audit, it is not dispassionate or scientific. It has an N of one, making it hard to generalize from, but that one is an individual who is affected by the system in profound and emotional ways.

The evocative audit draws on traditions of black, feminist scholarship to challenge the idea that dispassionate rationality is the only way to interrogate these powerful systems. In Joy’s work, the dispassionate, rational algorithmic audit is strengthened and complimented by an artistic intervention that shows why the systems are so important and so powerful. Joy would already have been heading off to a brilliant career as an activist (and I dare to hope, at some point, as an academic) based on her algorithm and auditing work, but the self-reflection she carries out in her dissertation work is truly extraordinary. I think it’s going give us a new set of categories for understanding the work that has to be done publicly to understand why audits matter so much to individuals and how the numbers and statistics behind these audits can be connected to real human lives.

Joy’s defense comes a few weeks after another brilliant defense coming out of Center for Civic Media. Alexis Hope’s work also began during her Master’s student years. Along with Catherine D’Ignazio and a large and passionate set of collaborators, she organized the “Make the Breast Pump Not Suck” Hackathon, bringing the visibility of the MIT Media Lab to a set of techno-social issues that rarely get considered in a technological context. Alexis’s work built from a personal narrative much as Joy’s built from the personal narrative of her invisibility in the face of machine vision systems. Alexis traces her interest in the breast pump to a conversation with Catherine D’Ignazio where Catherine talked about the frustrating and dehumanizing experience of using a machine that is fundamentally unchanged in its designed since it came out of the barn for milking cows. Alexis helped organize and lead four hackathons over the course of her academic career at MIT focused on different aspects of maternal and women’s health.

As she moved through the process of designing these interventions, her project of self-reflection and criticality stands as an example for anyone who hopes to innovate towards more just futures. Alexis reflected on the first breast pump hackathon, which was enormously successful in attracting press and sponsor attention, and concluded that it had failed in one critical way. The breast pumps designed at the hackathon move to the market as products, but those products cost between $500 and a thousand dollars, putting them out of reach of the people who most desperately needed a redesigned breast pump, low income workers who did not have parental leave and who had to return to work soon after giving birth. Alexis and her team recognized that the team they had assembled, while more gender diverse than most hackathon teams, was neither racially nor socio-economically diverse.

As Alexis went through the hard work of building a team to hack breast pumps for low-income mothers, she found herself confronting the reality that she and her colleagues had to do a great deal of work around anti-racism training and understanding their own biases before creating spaces that were open to participants of different backgrounds. Much as Joy’s dissertation reflected on the lessons learned in communicating these audits through personal experience, Alexis’s dissertation reflected on the intense and hard work necessary to create accessible and inclusive spaces to make real collaboration between people from different backgrounds.

The work of these two remarkable women has given me my own chance for self-reflection at an odd inflection point in my career. During the pandemic, I have left one institution for another and found myself welcomed as someone experienced and established in my field, which comes as something of a surprise to me. I have always thought of myself as an enfant terrible, an untrained scholar coming from the outside to disrupt existing systems. But I’m nearing 50 now. The beard I grew over the pandemic has come in bushy and gray. I have helped five students within the Center for Civic Media earn their doctorates and shepherded others through the process. There are six assistant professors at elite universities across the Northeast who’ve come out of my lab, and proudly, two of them are tenure track academics who like me, have not completed their terminal degrees. Somehow over the course of the pandemic, I have woken up and discovered that I have become a senior scholar, and I love it.

My aunt Jean had her pride and joy. These two remarkable young women are my Hope and Joy. I don’t know exactly how they will change the world going forward, but I have every confidence that their impact will be massive and positive. I do have a clearer sense for how their work will impact me. I understand now that my work is to help a next generation of thinkers understand that they have the power to transform the technological world for the better. My work at UMass centers on two key ideas. One is that we cannot limit ourselves to critiquing and then fixing broken technological systems. Instead, we must go further and imagine better systems that we could build in their place.

This is not a naked celebration of innovation for innovation’s sake, an embrace of disruption as a way of being. Instead, it is a recognition that begins from critique, looking carefully at the limitation and harms of technological systems, but daring to imagine not just tinkering with those systems and making them less harmful, but designing and building systems designed with entirely different intents: with the goal of making us better and stronger citizens and neighbors, with the goal of building technologies that do not calcify existing social injustices, but work to upend them. This project will certainly fail. But coming from a place of critique, it will be better positioned than existing technological systems to examine and wrestle with its own failures.

Second, I’m ready to dedicate this phase of my career to help and bring more people like Alexis and Joy through the academy and out into the world. UMass is making a bold investment in the field of public interest technology, a new field that seeks to help technologists have a positive impact on their communities by matching technological expertise with careful thinking about social change, to criticize, improve, and overturn unjust systems.

When I explain public interest technology to audiences, I fall back on the example of my friend, Sherrilyn Ifill, who runs the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund, the nation’s leading civil rights law firm. Sherilyn brought her team to the Media Lab to visit with Joy, me and my student Chelsea Barabas. She came to hear to about bias in facial detection systems – Joy’s work – the problems of carceral technology – Chelsea’s work – and to have a broader conversation about the role of algorithms and racial justice. I asked Sherrilyn why it was worth her time to bring her entire team for a day to an academic laboratory when such pressing work around civil rights issues lay in front of them.

Sherilyn explained that if the NAACP LDF had been able to stop red-lining in the 1950s, she believed the racial wealth gap between black and white Americans would be almost non-existent as opposed to the eight to one gap that it is today. “The next red-lining is going to happen via algorithm,” Sherilyn told me confidently, “and we need to understand those algorithms.” Sherilyn’s right, she usually is.

Public interest technologists are people who understand technology deeply enough that they can work within an organization like the NAACP LDF and help those fierce and effective lawyers understand the technology well enough to change the battlefield around discriminatory algorithms. Inspiring and amazing women like Joy Buolamwini and Alexis Hope are the sort of public interest technologists I hope to help bring into the world. Specifically, the work both of these women have done is so inspiring, it’s calling hundreds of other people to this subject. We now have the interesting challenge of trying to figure out how to educate these students so that they can follow in the paths established by my Hope and Joy.

I thought it was sweet and somewhat cheesy whenever Aunt Jean would show me her totebag. I’m beginning to understand the sort of pride one can have for people whose futures you’ve helped to influence, but whose trajectory and success is theirs alone. Congratulations, Joy. Congratulations, Alexis. And congratulations to anyone inspired by their example to follow in their footsteps.

Thank you so much for understanding this issues of cyber warfare perpetrated via facial recognition and fake algorithms which attacks women’s rights and aids systemic racism.

This connection was why received a Nobel nomination in 2005.

I have the issue of intellectual property since being a coder in the 80’s.

Not only are you seeing millions of versions of myself, I have no control over the intellectual property it creates.

A huge issue for us entertainers, as deep fakes are absconding with everything we create and no legal protection for the actual real talent.

Now the very brands like Oil of Olay who have profited for decades off this practice have adopted for their own with hashtags “#decodethebias†to divert any remaining income and visibility to their new marketing.

In other words, my complaint that “beautiful skin†basically apprises of millions of versions of myself is now being aimed back at me.

Let’s see the whole scenario for what it is…

Rebranding via plagiarism to save their unethical practice.

Ms Joy went straight down the rabbit hole with oil of olay’s campaign utilizing my social media banners, images and tweets to style their endorsement campaign.

This relentless practice has denied the voice of the 99.99% including the Sahawrian refugees living in the inhospitable outreaches of the Western Sahara I visited over 20 years ago.

#IPAintFree whether your #MIT or not!

Comments are closed.