I spoke this afternoon at the Trust and Safety Research conference at Stanford University. This is a new talk for me, and as is my habit, I wrote it out to make sure it held together. So this is what I meant to say, which may or may not resemble what I actually said on stage.

I want to share with you a story of the very early days of the trust and safety profession. In 1994, I dropped out of graduate school to work with one of the web’s first user generated content companies.

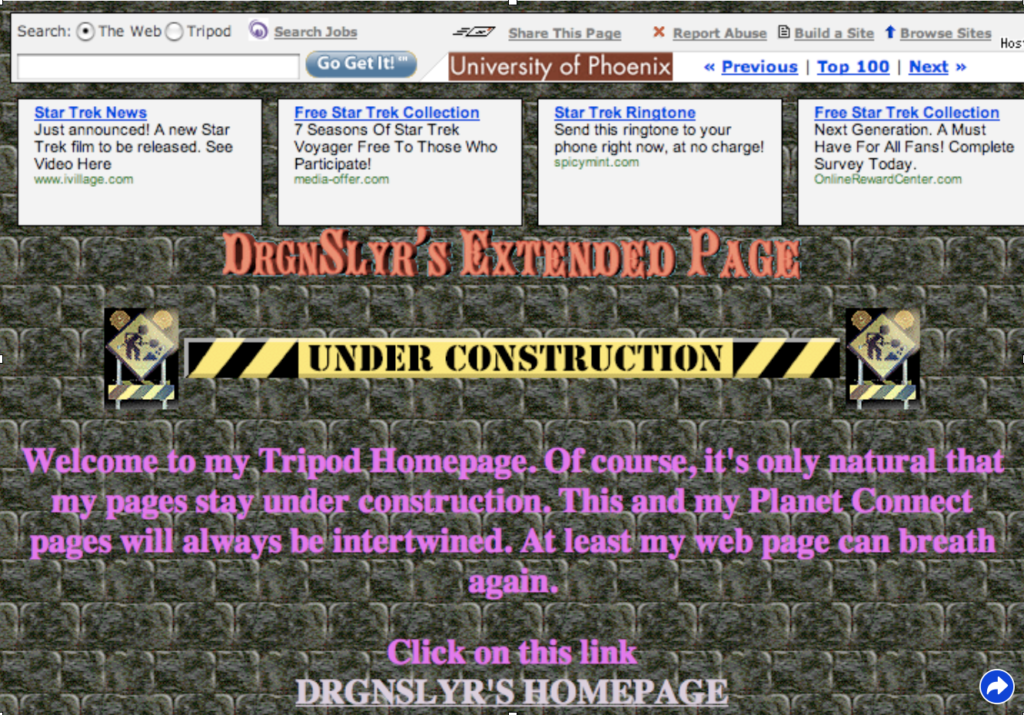

We were called Tripod, we were based in Williamstown MA, and for a little while in the late 1990s, we were the #8 website in the world in terms of traffic. Our main competitor was a better known site called Geocities – they ranked #3 – and both of our companies allowed users to do something very simple: using a web form, you could build a personal homepage without having to learn how to code and upload HTML.

Tripod got into this business literally by accident. We thought we were building a lifestyle magazine for recent college graduates, subsidized by the mutual fund companies who wanted to recruit young customers. Late one night, one of my programmers modified a tool we’d created to let you write and post a resume online and turned it into a simple homepage builder. We added it to the collection of web tools we hosted online and forgot about it, until I got a call from my internet service provider, telling me that our monthly bandwidth charges had increased tenfold. No one was interested in our thoughtfully snarky articles about life as a GenX 20-something – what they were interested in was what they had to say. We became a user-generated content business before the term actually existed, and that meant we had to build a trust and safety department.

Those terms didn’t exist either. When we started hosting webpages, it was before any significant legislation or legal decisions about platform moderation, which meant that when one of our users decided to upload copies of Photoshop and the Software Publishers Association came after us, it wasn’t at all clear whether we were criminally responsible for copyright infringement. We began hiring customer service representatives, building tools to let them rapidly review user pages and delete users who violated our terms of service with a keystroke. I wrote the terms of service, by the way – it probably would have made sense to hire a lawyer but hey, it was 1996. I was 23. Lawyers were expensive, and a little intimidating.

Over time, we ended up with a subset of customer service reps – the abuse team – who specialized in making hard calls about whether content should stay or go… or whether it should be escalated, including to law enforcement. You will be unsurprised to learn that child sexual abuse imagery was a problem for us as early as 1995.

The first time we reported CSAM (child sexual abuse material) to our local FBI office in Boston, it sparked an investigation into whether we’d violated federal law by sending imagery to the FBI over the internet. As a workaround we ended up copying evidence of CSAM to stacks of floppy disks and driving them three hours to the FBI field office every few weeks.

I tell you these stories not to make the point that I am old: my students at UMass make that point to me regularly. It’s more to give you an insight into how some of these questions we wrestle with today came to be. If what’s happening in online spaces is harming individuals, or society as a whole, how should we deal with it? What I want to impress upon you is simply how adhoc, how built on the fly many of the infrastructures of the participatory web were… and are.

Not just at Tripod, but across the early internet, we took the path of least resistance, building systems that worked well enough, which became embedded into norms, code and policy over time until they simply became the way things were done. We chose to handle content that violated our terms of service using a customer service model because it seemed like the easiest model to emulate.

What’s strange, in retrospect, is that lots of the people who built Tripod grew up on the academic internet, where things worked very differently. I and many of my colleagues were veterans of MOOs and MUDs, basically text-based, online, multiplayer virtual worlds, where violations of the community’s rules and norms could turn into complex community discussions and debates. One of those debates was immortalized by author Julian Dibbel in a piece called “A Rape in Cyberspace” about sexual harassment on a platform called LambdaMOO. The administrator who ultimately banned the abusive user, after robust community debate, had the terminal next to mine at the Williams College computer lab. We came from a tradition on which users of computer systems were treated as responsible adults (even if we weren’t), who should be responsible for governance of our own online spaces. But when it came to building the consumer web, it’s like we forgot our own past, our own best instincts for how online spaces should work.

I have many regrets about my work building a company that helped pave the way for Friendster, MySpace and ultimately Facebook and Twitter. I’ve spoken before about my regrets about creating the pop-up ad, and if you find me after this talk, I will tell you the story of how our tools to keep pornography off Tripod cost our investors at least a billion dollars.

But my biggest regret is that we unquestioningly adopted a model in which we provided a free service to users, monetized their attention with ads and moderated content as efficiently and cheaply as possible. We didn’t treat our users as customers: had they paid for their services, we probably wouldn’t have been as quick with the delete key. And we certainly didn’t treat our users as citizens.

Here’s why this matters: since the mid-1990s, the internet has become the world’s digital public sphere. It is the space in which we learn what’s going on in the world, where we discuss and debate how we think the world should work, and, increasingly, where we take actions to try and change the world. There is no democracy without a public sphere – without a way to form public opinion, there’s no ways to hold elected officials responsible, and no way to make meaningful choices about who should lead us. This is why Thomas Jefferson in 1787 told a friend that he would prefer a republic with newspapers and no government over a government without newspapers.

There is a litany of woes about our contemporary public sphere. The market-based system that produced high quality journalism for the twentieth century may be fatally crippled by a shift of advertising revenue from print to the internet. We have legitimate worries that social media spaces may be harming individuals, undermining people’s body image and self esteem, pushing vulnerable people towards extremist ideologies. We worry that the internet is increasing political polarization, locking us into ideological echo chambers, misleading us with mis- and disinformation.

How valid are these concerns? It’s complicated, and not just because social science is complicated, but because it’s incredibly difficult for independent researchers to study what’s happening on social media platforms. We know significantly more about some platforms than others – Twitter became the Drosophila of social media scholarship by making communications public by default and giving academics access to APIs useful for scholarship – but a study colleagues and I conducted in 2020 and 2021 of social media scholars found that none of us believed we had access to the data we would need to answer key questions about social media’s effects on individuals and society. This included researchers who were designing academic/industry collaborations like Social Science One.

This is why I’ve joined scholars like Renee Di Resta, Brendan Nyhan and Laura Edelson in calling on platforms to release vastly more data about moderation decisions, about how they redirect traffic across the internet, about the effectiveness of techniques used to reduce information disorder. It’s why I’ve worked with activists like Brandon Silverman – the founder of Crowdtangle – on legislation like the Platform Accountability and Transparency Act, designed to ensure that information about what information and misinformation is spreading on platforms like Facebook can be reviewed in real-time by scholars and policymakers alike. But I am increasingly convinced that we cannot just work to make existing social networks better – we need to reconsider the roles of social networks in our public sphere, and build networks that actively help us become better neighbors and better citizens.

My dear friend Rebecca MacKinnon published a wonderful analysis of tech platforms about a decade ago, titled Consent of the Networked. She argued that platforms like Facebook behaved as if they were monarchs and their users were subjects. At best, we might hope for a more benevolent monarch, one that would recognize that their subjects had basic rights, as England had done with the Magna Carta.

An interesting thing happens when you treat people like subjects: they don’t gain experience in being citizens. Two decades ago, Robert Putnam published Bowling Alone, his influential argument that Americans were losing connective social capital as we abandoned real world interactions in spaces like bowling leagues. Worried about the implications of Putnam’s work, Scott Heifferman started Meetup to try and build real-world social ties between people who met up online.

It turns out that social media may have counterbalanced some of the worries Putnam had about losing weak ties. Tools like Twitter and Facebook are actually amazing at helping us maintain lightweight connections to people we might otherwise have lost. But there’s another prediction that Putnam offered that’s got important implications. Participation in public life, even in serving as treasurer of your bowling league, trains us in the practical skills of making a democracy function. Whether at the PTA or the Elks Lodge, civic participation trains us how to run a meeting, how to take turns and make sure the voices in a room are heard, and critically, how to have a constructive disagreement.

What happens when we move from the physical spaces that we – as citizens – are collectively responsible for moderating into digital spaces moderated by people half a world away? What happens when decisions about what is allowable speech are made by people half a world away, guided by the judgments of opaque algorithms, following rules written in three ring binders? Our public sphere is no longer helping us become citizens – it’s training us to be subjects, and specifically the subjects of large internet companies.

There is a different way to moderate online spaces. The first step is to get rid of the word “moderation” and take seriously what we’re actually doing, and that is “governance”. In most online spaces, governance comes from a powerful and distant authority, whose decisions we have no power to challenge. It’s a form of serfdom, inasmuch as the lords provide the digital land and take a share of our crops – attention – in exchange for our continued right to exist.

It doesn’t have to be this way. We can take the lead from online spaces that have embraced governance as an alternative to serfdom. Reddit has taken a significant step in the right direction, giving moderators the ability to set their own community standards for their online spaces, allowing them to become digital dictators or democrats on a small scale. Nate Matias at Cornell has been working with communities on Reddit and elsewhere to conduct experiments in making online communities more resistant to mis and disinformation and more welcoming to new users. The best online communities don’t just govern themselves – they actively seek ways to become better self-governed spaces.

I’ve been working on a book with my colleague Chand Rajendra Nicolucci called An Illustrated Field Guide to Social Media – it’s an exploration of just how diverse and different social networks can be. Some of the most inspiring communities we’ve learned from are communities built by digital emigrés. These are spaces built by users who left platforms that they had no hand in governing for ones where they could help shape the rules of the road. Casey Fiesler at UC Boulder has helped us learn about An Archive of One’s Own, an amazing community built by fanfiction authors who went through an intense founding process to create a space that they designed, built and run, specifically for the needs of authors. AO3 serves more than five million users a month, and has given rise to an activist organization that advocates for fair use, and an academic journal that studies fan community and creativity.

My own work is on small social networks for civic purposes. We’ve built a social network called Smalltown that communities can use to run carefully moderated conversations about local civic issues, increasing the number of people that are able to participate. We lovingly refer to it as the world’s most boring social network, because the conversations are respectful, civil and about such hot topics as parallel versus back in angled parking. We’re in the early stages of building a music discovery network called Disco, trying to create a space outside of the shadows of Amazon and Spotify that puts control back into the hands of music fans. Our goal is for these communities to be carefully moderated, and to put as much governance as possible into the hands of the most committed users.

These projects are part of a larger effort to build a flourishing ecosystem of smaller social media platforms. This requires not only software to build and manage those communities, but technical and policy changes as well. For example, we are working on a project called Gobo, a social media client that is loyal to you, the user, rather than to the social media platform. Gobo gives you control over what you’re seeing on different social networks: you can choose the algorithms that sort the various posts competing for your attention, and test those algorithms to see how they work. This work is technically possible, but it requires a very different regulatory environment than the one we currently have, one that mandates interoperability and protects adversarial interoperability, the ability to build a product that announces “I’m going to be compatible with you whether you like it or not.â€

The ecosystem my friends and I are building includes both large and small social networks. I don’t just want you to have control over Smalltown – I want to give you control over Facebook, as well, using the tools you choose to determine what content you see. And I hope that, in some cases, you may be sufficiently invested in these communities to help govern them.

But in a room full of people who study trust and safety, there’s an obvious problem, which is that people are terrible. Left to their own devices, people create Stormfront. They create Kiwi Farms. They create 8chan. Very quickly, groups of people online are capable of degenerating into some of the most toxic, hostile, and destructive communities we’ve ever seen.

I have two responses. The first is a hopeful one. I firmly believe that there are more people who want to create supportive, positive, democratically-governed communities than those who want to create spaces for toxicity and hatred. And I believe that if we design for the worst humans have to offer, we will inevitably build communities where humans are at their worst.

But second, I believe there are lessons we can learn, including from the large platforms that have been combating toxicity on their platforms since their advent. To create the sort of social network universe I’m talking about, we need tools like the remarkable fingerprint database of child sexual abuse material that Facebook and others have constructed and used to prevent CSAM on their platforms. We need to find a way to make resources like this and databases of extreme and violent content both accessible to people who are building these new social networks and auditable, so that we can be sure that these tools are not being used to silence legitimate speech.

We are also learning techniques that are proving helpful when people use our tools to create communities in conflict with our values. When Gab.ai started using the core code of the Mastodon social network, Mastodon’s developers were faced with a dilemma. As an open source project, they couldn’t legally prevent Gab from using their tools. Instead, they tried something simpler. They do not federate with Gab, which is to say they do not exchange traffic between their communities and Gab’s community. When extremists use our tools we should work to make their audience as small as possible, and make it difficult for them to operate. But we cannot allow the existence of Nazis to prevent us from building better platforms for social media.

In 2022, it feels like American democracy itself is under threat. I think many of us in this room have an intuitive sense that social media has at least something to do with that threat. But let’s be clear, we’ve gotten the public sphere that we have paid for. We paid nothing, and in exchange, we got a public sphere that puts us under perpetual surveillance, and in many cases, seems to amp up our worst tendencies for how we treat one another.

It was naive to believe that we would get something beneficial for nothing. In the same way that we are discovering that if we want quality journalism, we must pay for it either with a subscription or through public media, we are discovering that we need to make real investments in the spaces in which we interact with each other online. Once you let go of the idea that social media is a space in which we can make gajillions of dollars and think instead about the challenges of making a more robust and functional democracy, all sorts of exciting new models open up.

If you open yourself to the idea that democracy cannot exist without a healthy public sphere, possibilities open up like the idea that public media outlets might get involved with building this next generation of the healthy digital public sphere. Indeed, this is already happening. I work closely with a group in the Netherlands called Public Spaces, a coalition of public broadcasters and cultural institutions who are hard at work helping their institutions lessen their dependence on surveillant software and trying to build tools that are more consistent with their community values.

Imagining social media as something that could help us become better citizens and better neighbors is the first step in reclaiming and repairing our digital public sphere. This work is not easy, but it is possible, but only if we believe it’s possible. The first step in believing it’s possible is understanding that our task is not only to fix what’s broken with existing social networks, but to take on the harder but rewarding work of building social media that could be good for us as individuals and as a society.

Pingback: Building Tech “Trust and Safety†for a Digital Public Sphere - IDN InDepthNews | Analysis That Matters -

Pingback: Building Tech “Trust and Safety†for a Digital Public Sphere - IDN InDepthNews | Analysis That Matters - Usa News Quickies

> so that we can be sure that these tools are not being used to silence legitimate speech.

So all you want is more effective censorship by leftists, who are given carte blanche to decide what counts as “illegitimate speech.”

I’ll take the unaccountable money-grubbing corporations over evil zealots, thanks.

Pingback: I was the head of trust and safety at Twitter. This is what could become of It. - Rifnote

If you look at platforms like HIVE or Whaleshares, blockchain blogging platforms, you’ll see community governance at work. Users basically upvote and downvote content they see. If there are too many downvotes, the content is hidden. The more upvotes, the more prominently the content is featured in some parts of the sites.

Of course, there are sometimes downvote wars, as is the nature of people. And harassing users, copyright infringers, etc. It all gets encountered and additionally you have the complications where money is involved and people try to game the system for personal gain.

What I’ve seen being in a number of these community, even creating onboarding materials for some, is that they all fail to successfully create spaces that are both non-hostile for everyone there and fair in the distribution of attention and funds.

Ultimately it seems that Republics are better than Democracies. We need things like the moderation board Musk has promised to bring to Twitter, but with transparency and user input. We need to be able to elect our moderation board members, so that the people who think ‘the vaccine prevents the spread of c19’ and those who think ‘the vaccine only decreases the severity of infection with c19’ both get to have representatives deciding which of those statements (both? neither? just one?) get to be shown, and how prominently.

How many sexes are there? Is a Nigerian white or black? These are all questions with a diversity of answers among honest, intelligent people. Just as we get to choose who represents us in government offline, deciding whether the right to life or the right to bodily choice should take precedence in law, we need representatives in online governance too.

Pingback: Opinion | What’s Twitter’s Future? The Former Head of Trust And Safety Weighs In – The New York Times – NewsX

Pingback: The birth of a new crypto threat to government - POLITICO

Comments are closed.