Why do you live where you live?

If you’re like most Americans, your family may have chosen where you live. The typical American lives 18 miles from their mother. (This varies widely, from the mountain west, where distances are 44 miles on average, to the Mississippi delta, where the figure is only 6 miles). While pundits have predicted that Americans are moving to be near our ideological peers (See Bill Bishop’s The Big Sort) our default is not mobility, but stasis.

More to the point, Americans move a lot, but lots of those moves are local. In a given year, 87% of Americans are in the same house as last year. 9.9% have moved in the same state. 2.4% have moved from one state to another. (Calculations based on US Census Bureau State to State Migration Flows, 2021)

Cross-state mobility is a privilege of wealth. If you’re poor, you’re more likely to depend on networks of family and friends, and the social cost of moving to another city or state is much higher than for someone moving from Boston to Austin to take a high wage job. (You are more likely to move often than the wealthy, but often within the same city or neighborhood due to eviction, leases expiring, etc.)

In a powerful example of the relationship between wealth and mobility, consider Texarkana, the pair of cities that straddle the Texas/Arkansas border. With the advent of “Obamacare”, residents on the Arkansas side of the border had access to subsidized healthcare, while those in Texas did not. Despite the fiscal incentives, very few Texarkanas moved… despite the fact that the cities literally interconnect, and moving from one state to another simply means crossing a street, State Line Avenue. So few people moved to obtain Obamacare that social scientists used the example to disprove the “welfare magnet” hypothesis, the idea that people will migrate from low-benefit to high benefit states. Turns out the people who would benefit most from moving have the fewest means to move, and would risk disrupting their support systems if they did.

If wealth and family outline the boundaries of American mobility – other major factors include military service, which rotates service members throughout posts, or higher education, which sends many young people out of their home towns – there is another major pattern we must consider. Since the 1950s, a deep societal shift has changed where Americans live: Americans have migrated from the Rustbelt to the Sunbelt.

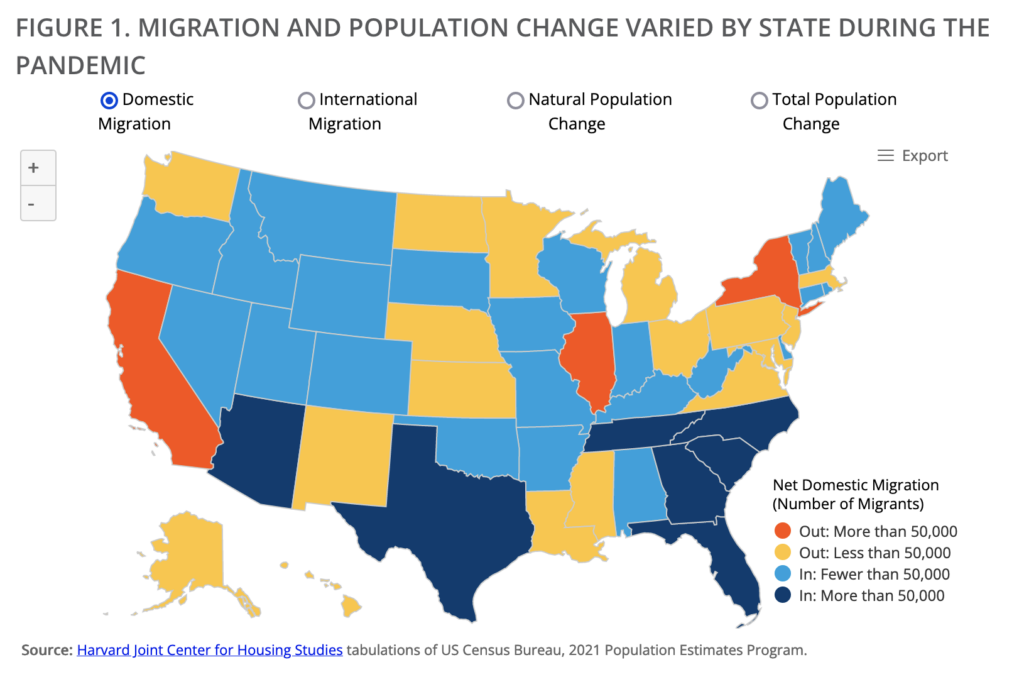

Migration during COVID, from Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies

(These are both controversial terms, though in slightly different ways. “Sunbelt” was coined by a Republican strategist, who saw migration to the new suburbs of the South and Southwest as an opportunity to establish a permanent Republican majority. The Rustbelt is a sometimes derogatory term for the industrial cities of the Great Lakes region, who dominated US manufacturing in the first half of the 20th century. Neither term is exact – is Arkansas sunbelt, or merely southern? Are former New England milltowns rustbelt? – but both are widespread.)

This shift is long, dramatic and still ongoing. In 1950, 55% of Americans lived in the Northeast and the Midwest. Now 38% do. (Calculations based on US Census data.) Cities like Detroit and Cleveland have now roughly one third of the populations at their peak, while cities like Houston and Phoenix have emerged as major metropolises. And the shift continues – the majority of the fastest growing cities in the US between 2010 and 2020 are in the sunbelt, primarily in Texas and Florida.

Most of us have lived our lives entirely during this migratory wave, so the impetus to move south and west feels more like natural law than sociological phenomenon. Who would’t want to trade snowy winters for beaches and golf courses? Once air conditioning and automobiles were widespread and cheap, who wouldn’t move to Florida?

In truth, the story is much more complicated, and has less to do with personal preferences and more to do with economic and political forces. Southern cities, led by Barry Goldwater in Phoenix, carried out a sustained campaign for a new economic model: the “high growth” city, where low taxes, lax zoning, low regulation and anti-union policies attracted Northern manufacturers and allowed for cheap housing to be built. (I’m borrowing here from Elizabeth Tandy Shermer’s excellent “Sunbelt Capitalism: Phoenix and the Transformation of American Politics”.) Economists who’ve sorted through the different factors believe that economic incentives – good jobs and low cost of living – were a more significant factor in population shift than the “amenities” of warm winters and outdoor recreation. (See Glaeser and Tobio, 2007, The Rise of the Sunbelt.)

Yet the factors behind the migration are changing over time. Housing is no longer cheap in much of the Sun Belt – the counties that built the most housing units between 2010-2020 had an average median home price of almost $500,000, while median homes in Detroit and Cleveland sold for about $200,000. (Smaller rustbelt cities are even cheaper – median home price in Utica, NY, perhaps my favorite post-industrial city, is $162,000.) (Data from Redfin, 2022 median home prices for relevant counties.)

But beyond the prices, there are excellent reasons to buy in the rustbelt rather than the sunbelt in 2023.

Climate risk has become an inescapable reality across the US – it was already inescapable for those on the frontlines of wildfires or hurricanes. But 2023, between sustained heat waves and wildfire smoke from Canadian fires, made clear that everyone is going to be affected by climate change, though it’s going to be adaptable for some and devastating for others. Insurers are starting to refuse to cover some parts of the US most likely to experience severe climate change. Yet, these price signals haven’t yet changed behavior – Americans are still flocking to cities most likely to experience serious effects from climate change.

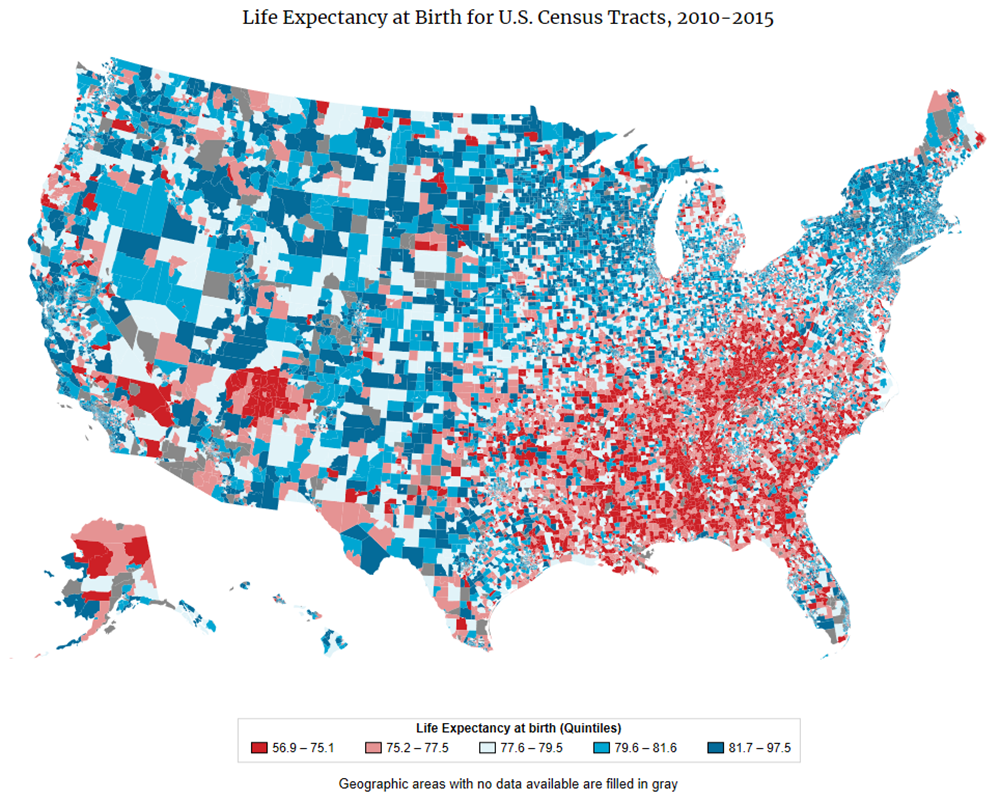

Life expectancy at birth for US census tracts, 2010-2015. From https://www.cdc.gov/surveillance/blogs-stories/life-expectancy.html

These patterns preceded COVID but have gotten more dramatic since the pandemic.

There’s another risk associated with the moves south and west. Life expectancy is shrinking in the US – not uniformly, but particularly in regions of the country that have most aggressively embraced the “high growth” model. One hypothesis argues that Southern states invest less in schools and hospitals, and are much less likely to regulate dangerous behaviors than states with a stronger social welfare system. These factors don’t explain all the disparity between the counties with the lowest life expectancies in the US and those with the longest – the deadliest counties in the US are all ones containing reservation lands, and Native Americans have seen the greatest decrease in life expectancy. But they help explain why moving from a county in the southeast to one in the northeast – even at age 65! – correlates to living longer.

(Discussions of where we live are emotional, and I’ve seen an enormous amount of skepticism around the connection between geography, governance and mortality. The most convincing paper I’ve found on this topic is Place-Based Drivers of Mortality: Evidence from Migration, Finkelstein, Gentzkow and Williams (2021)

Using Medicaid data, the authors study the relationship between place and mortality for a set of people over 65. Researchers create a natural experiment by selecting those who migrate during the period from one metro area (census zone) to another and compare to those who remain. They find that moving from a low life expectancy area (10th percentile) to a high life expectancy area (90th percentile) correlates to a 1.1 change in lifespan. They see similar effects in moving from 25th to 75th percentiles, though less dramatic.)

So, we have something of a paradox. People used to move from the rustbelt to the sunbelt, seeking cheap housing and plentiful jobs. But now, housing in rustbelt cities is cheaper than in many sunbelt cities, and with unemployment low, jobs are available across regions of the US. Cities like Phoenix, Dallas and St. Augustine – which are attracting massive influxes of population – counterbalance immediate quality of life with long-term risk, risk of losing your home to climate-related disasters, or of shortening your life though living in places with more dangerous behaviors (car accidents, gun violence) and fewer health resources.

In other words, we keep moving from Cleveland to Phoenix, when it might well be time to move from Phoenix to Cleveland.

“Wait one second, Ethan – you’re a scholar of internet communities. What does this have to do with the issues you work on?”

It doesn’t, at least at first glance. But it’s a set of questions I’ve become increasingly obsessed with over the past decades.

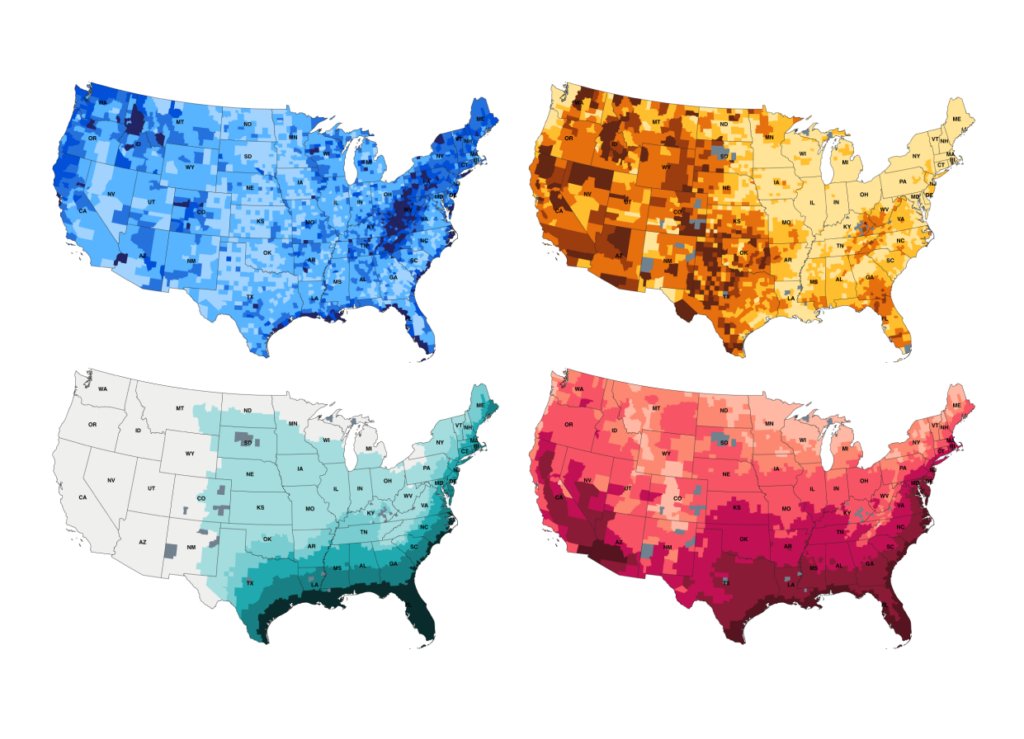

Four maps of climate risk from First Street Foundation – Upper left is flood risk. Upper Right is fire risk. Lower left is wind risk. Lower right is heat risk.

I have lived in Western Massachusetts, in a small town just outside the small city of Pittsfield, MA for the past three decades. I moved here as a college student and stayed. (I live 47 miles from my parents, for those checking, though for the record, they moved to be closer to me and my sister. And my sister helps balance out my statistical anomaly by living only a mile from my parents.) Where we live is beautiful, reasonably affordable (cheaper than the vast majority of New England, though more expensive than the Great Lakes region), filled with museums, outdoor activities, and has low unemployment. We are largely insulated from the most dramatic effects of climate change – climate risk models developed by First Street Foundation give Pittsfield moderate risk of flooding and wind damage, minor risk of wildfire and extreme heat, a much lower level of risk than not just Sunbelt cities, but also “superstar” cities like Boston and New York City.

Yet our community keeps shrinking – Pittsfield has lost about 5% of its population per decade for the past fifty years. My wife Amy, moving from Houston (where the house across the street routinely flooded, but where the population is always growing), worried about the wisdom of owning property in a shrinking part of the country. I’ve started feeling a strong sense of solidarity with communities who’ve seen their populations shrink, and have been visiting these cities to understand what sorts of problems come with a decreasing tax base, as well as what opportunities exist to transform these places.

This past autumn, I gave a talk about legacy cities at the PopTech conference, reporting on a road trip Amy and I took to Detroit via Utica, Rochester, Buffalo, Cleveland and other post-industrial cities. Friends who were surprised to find me talking about urban geography, rather than social media, observed that I seem more passionate at the moment about the possibilities of revitalizing Syracuse, NY than I do about the chances of rescuing Twitter from its insane owner. I’m choosing to lean into the passion I feel for these cities, using it as impetus to learn about American economic history, public health, climate resiliency, and a dozen other topics I have no formal training in. (In my defense, I have no formal training in internet studies, communications, public policy or any of the other fields I teach classes in :-)

Here are two hypotheses I am experimenting with.

H1) The migration from the rustbelt to the sunbelt is driven at least partially by narrative: stories about American opportunity, independence, frontier spirit as well as memories and myths of pollution and decay in northern cities. A migration from Phoenix to Cleveland requires addressing these stories and writing new ones, as well as arguments based on facts and figures.

H2) The legacy cities I’ve grown to love are becoming “gateway cities” (Michelle Wilde Anderson, “The Fight to Save the Town”, 2022), places where immigrants and particularly refugees get their footings in a new country. Cities that welcome refugees (Utica, NY – see Susan Hartman, “City of Refugees”, 2022) are especially well positioned for this shift, as we’re about to see wave of climate refugees, first from vulnerable developing nations, and eventually from vulnerable parts of the US.

As I try to figure out what to do with this new research interest, I’m hoping to write more here, on this blog, a place I used to figure out my first book, Rewire. There are some intimidatingly smart books coming up about the US and climate change – I am hugely looking forward to Abrahm Lustgarden’s forthcoming “On the Move: The Overheating Earth and the Uprooting of America” – but I also think there’s room for some hope.

The next few decades are going to be very rough ones for our planet and everyone who lives on it. Humans adapt – it’s what we do. Adaptation in the coming decades is going to involve thinking very seriously about where we live and why, and I’m hoping that rethinking our cities is part of responding to the forthcoming changes with an eye towards possible, better futures instead of mourning our current, soon to be past.