I’m in Paris this week – spring break for UMass – visiting my second-favorite university, SciencesPo. I’ve taken on a new responsibility with SciencesPo, with a new initiative – l’institut libre des transformations numériques de Sciences Po – where I am leading a board of stakeholders advising the project. To spend some time with my colleagues – and to enjoy somewhere slightly warmer than western Massachusetts – I’m spending the week at SciencesPo, enjoying both planned and chance encounters.

One of those encounters is with Pablo Boczkowski, a brilliant media scholar normally based at Northwestern University. Boczkowski has written extensively about how news is produced and consumed in a digital age. I had not realized that media theory is a second profession for Boczkowski – he trained and practiced as a psychologist in Buenos Aires before becoming a media scholar. That helps make this talk make more sense. Titled “Digital Freud: The Refiguration of Inequality, Society and Personhood in Clinical Practice”, it’s an overview of his new book, based on ethnography of mental health professionals in the city of his youth, Buenos Aires. Citing Gabriel Garcia-Marquez, he promises “A strictly accurate account that sometimes ventures into fantasy.”

The focus is on the adoption of digital technology by psychologists and psychiatrists, and focuses on Buenos Aires because it is – arguably – “the world capital of mental health workers”, if not of mental health. Boczkowski reports that there are eight times as many mental healthcare professionals, per capita, in Argentina than in the US. That concentration is particularly high in Buenos Aires, possibly three times of what might be found in smaller cities. Pablo argues that the rise of telehealth, the routinization of digital technologies and the widespread adoption of the mobile phone represents “the first major socio-material transformation in the profession in more than a century.”

Why focus on the mental health field? Already, one out of eight people worldwide report problems with mental health. After COVID, as many as 1.5 billion people may be experiencing mental health problems. Boczkowski’s argument is not that tech is causing these problems (he refers to that as the Jonathan Haidt’s position) but that the changes brought about within the mental health field may help us understand some broader transformations around technology, civics and society as a whole.

Two stories run through Boczkowski’s talk – one is his personal story of return, visiting the hospital where he first practiced. The second is the tragic death of Jorge Marcheggiano, a seventy-year old patient of a state mental hospital who was killed by a pack of wild dogs when walking in a courtyard at his hospital. The failures of technology to protect Marcheggiano, the overwhelmed systems that failed him help motivate Boczkowski’s exploration of these questions.

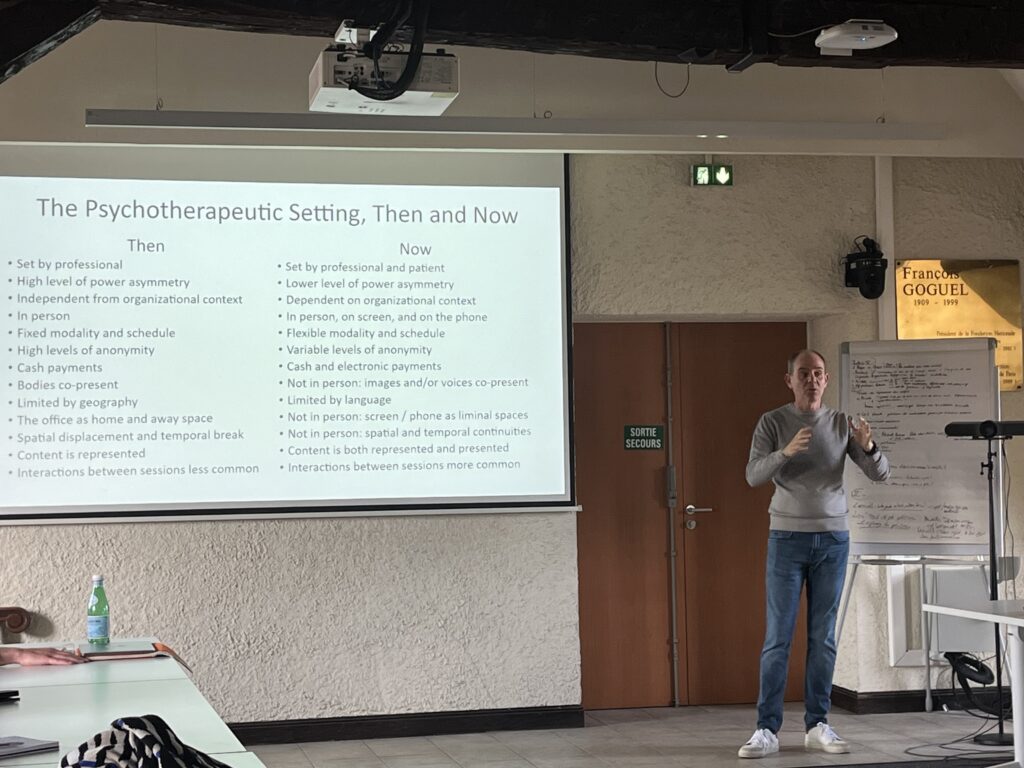

In many ways, the environment of the mental health office is unchanged – treatment rooms with bare walls and two chairs still dominate the setting. But actually the setting has changed radically, particularly during COVID. The 19th century model of psychology, where the therapeutic setting is set by the professional, where he or she has the “home court advantage”, was utterly upset by the new rules of a digital, post-pandemic world.

Adapting to the pandemic meant that one therapist reported doing a couple’s session with the woman in a car, the man in the house and the therapist in a third location, something that she would never have allowed to happen before this digital shifting of time and space. Patients no longer have a travel to the doctor’s office to think about what to say, or a return to process what’s been said and heard. Instead, you move from real life into a session seamlessly. And even when mental health professionals try to maintain distance from their patients, anonymity is much less possible. The Zoom window is an insight into a patient’s home, circumstances, class, situation… and vice versa.

The therapist used to be a fairly anonymous figure. Now, if you are even modestly active on social media, your life is wholly visible to your clients. They know what your kids are into, and when your birthday was… and they may expect you to keep up with them in a similar fashion.

The changes from the rise of the digital are not just incidental. The professionals Boczkowski interviews report that their patients now come to sessions with “evidence” – text messages that show the dynamics of a relationship, recordings of a family dinner that show a family member’s behavior.

The phone can be a space for bonding and connecting with young patients in particular – some of Boczkowski’s interview subjects document trading memes with their patients, or having conversations with patients about whether the “stickers” they use in text messages are lame or up to date.

The most profound changes are around time: psychiatrists, in particular, report being deluged with requests for prescriptions – and not just mental health medications – at any time if they’ve shared their mobile phone numbers with patients. (Psychologists report less concern about contact between sessions, and more about distraction during sessions with phones and social media. This may be because psychiatrists face a massive caseload – 300-400 patients contacting you for prescriptions could be overwhelming, while a psychologist might have 50-100.)

(I’m extrapolating slightly from Boczkowski’s remarks here and might be getting it wrong. He references class as another factor in the boundaries between professional and private life. Many psychologists work 30/hrs a week for state hospitals or other institutions, making very little money, and then work with individual clients in private practice. I get the sense that sharing one’s mobile number started with private clients, and may be less common sharing with patients at the public hospitals.)

While there’s a temptation to reinstitute the strict boundaries between work life and private life, there’s good reasons for some permeability. An interview subject tells Boczkowski about caring for a patient experiencing domestic violence who had to reach out 3-4 times a week. While this might be seen as a major demand on a therapist’s time, it was also what this woman needed during crisis, and her therapist was able to help her leave her home and get to a safe place. The strictness of separation between the personal and the professional has always been more for the professional than the patient. (Boczkowski points out that Freud’s couch was instituted not for therapeutic reasons, but because Freud hated being stared at by patients for hours a day.)

There’s a dark note throughout the talk, with both the story of the patient killed by wild dogs, and

the rise of depression. One interview subject observes that by 2050, the WHO has estimated that depression will be the main cause of morbidity on the planet. Why? As the interviewee puts it, “We have utterly failed to design a world in which we can all live.”

Mental health professionals deal with the failure of our world with three techniques: reification, justification, and sometimes, reparation. Reification accepts the troubled state of the world as a self-evident given. Justification attempts to explain away the status quo as the function of different schemes of work, an understanding of unfairness and inequality through effort or skill. Some therapists find themselves attempting to repair, donating services like Wifi plans or cellphone service to patients, trying to supplement the state’s deficiencies, in part so they can continue helping their clients. These interventions are pragmatic, not ideological.

In the final minutes of the talk, Boczkowski makes a number of leaps that I find fascinating, but worth interrogating closely. He suggests that the situation we’re experiencing with the transformation of mental health work in Argentina exemplifies a broader state of “demand rules”, a situation in which the individual prevails over the institutional system. These institutions fail to satisfy a demand that, in many ways, is impossible to satisfy – this demand to be heard, to be healed, not just personally, but a healing of the world. When this demand cannot be satisfied, it is no wonder depression is on the rise.

We are experiencing new ways of being in the world, which Boczkowski refers to as “deregulating personhood”. We are always available, always on, we are exhibitionists as mediated by social media. This world rewards flexibility, pragmatism and improvisation. It demands limited balance and boundaries between work and personal life.

Associated with this shift, Boczkowski – and those he interviews – see a desire for immediate gratification and low tolerance for frustration, anxiety and loneliness. When people encounter these feeling they have low tolerance for, they can react with intolerance, extreme views and polarization. We are therefore experiencing the re-regulation of the political as well as the personal, seeing a rise in extreme ideologies and the rise of individuals who embody this intolerance and extremism, like Javier Millei (or, I suspect Boczkowski might agree, Donald Trump.)

I questioned Boczkowski about causality: do we see these changes in society as caused by the sorts of digital shifts this research documents, or do we see those shift accompanying a rise in both anxiety and depression from the collapsing environment, democracy under threat and the inequities of our current economic system? Boczkowski emphasizes that he doesn’t see the cause as technological, but is looking at a deeper pattern. He notes that distrust in democracy in Argentina is at an all time high, perhaps in part due to the persistence of marginalization for many communities. He suggests we see his work as bridging between the larger story of social transformation and the transformation of what it means to have a psychological consultation. “This book is not a causal story, but it is the experience of those trying to alleviate the suffering.”

Boczkowski notes, “The perfect storm is real – people are suffering and those treating them are also overwhelmed.”

I’m looking forward to the book, and particularly to hearing more of the argument around “demand rules” and how this might explain the broader global political moment. More than anything, I’m enjoying watching a scholar I’ve long admired pivot from familiar topics to the less familiar, in a way where he’s clearly energized by the new work.