Florida is preparing for Hurricane Milton, the second significant storm in two weeks to impact the southern US. Hurricane Helene killed at least 220 people and caused horrific damage in North Carolina, many miles from the coast, where massive rainfalls triggered widespread flooding.

These storms are likely part of a new normal, in which warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico evaporate more, supercharging storms with more wind energy and greater rainfall. A chart in the New York Times shows just how warm this season has been compared to the already warm past decade – surface temperatures for much of the Gulf is 90F (32C), and this excess heat was predicted to lead to a terrifying hurricane season for 2024. Those predictions seem to be coming true.

In late August, 99% Invisible, the wonderful podcast from Roman Mars and crew on design and urbanism, ran a six-part series produced by Emmett FitzGerald called “Not Built for This”. Examining the surprising brittleness of American infrastructure in the face of climate change, the series is a portrait of a country that’s being transformed and doesn’t realize it yet.

The series takes on some of my favorite topics including managed retreat (offering incentives to move people from the most vulnerable neighborhoods to safer places), the perverse incentives that surround the insurance industry and its regulators, and the idea that there may be biological maximum temperatures that species – including humans – cannot adapt to.

The series does what good climate coverage must do: pair scientific fact with great storytelling, giving us the voices of people who are being forced to make major life changes. Some of those life changes include moving – one of the most powerful stories is of a woman pressured out of her neighborhood in Lake Charles, Louisiana by a buyout, giving her money for a house that would likely be unsellable otherwise. While the funds allow her to move to a less flood-prone neighborhood, it takes her from a tight-knit Black community and puts her in suburbia, and she wonders why the city couldn’t have invested instead in making her neighborhood more resilient.

The message of the series is in the title: our infrastructures were simply not built to survive the sorts of extreme weather that is rapidly becoming routine. There are some ironies to this: Lake Charles is a city built to serve the oil and gas industry, and it’s been one of the most profoundly affected by climate change, with rising sea levels, risk of storms and serious heat risk. (Risk Factor from FirstStreet.org lists heat and wind risks for Lake Charles as Extreme, its highest category, and flood risk as moderate, rising to major for its roads and infrastructure.) Tampa, squarely in the sights of Hurricane Milton, is similarly understood as a high risk location with major flood risk, and extreme wind and heat risk.

But you don’t have to be on the Gulf Coast to be at high risk from climate change. The New York Times ran a story titled “Climate Havens Don’t Exist”, noting that many people had moved from coastal North Carolina to the mountains surrounding Asheville, only to face the wrath of hurricane Helene. The dangers of the Asheville area were known to people who model climate change – while Asheville itself was known to have major flood risk (the fourth of six levels in FirstStreet’s models), Chimney Rock Village, NC, which has sustained some of the most significant damage, was known to have severe flood risk.

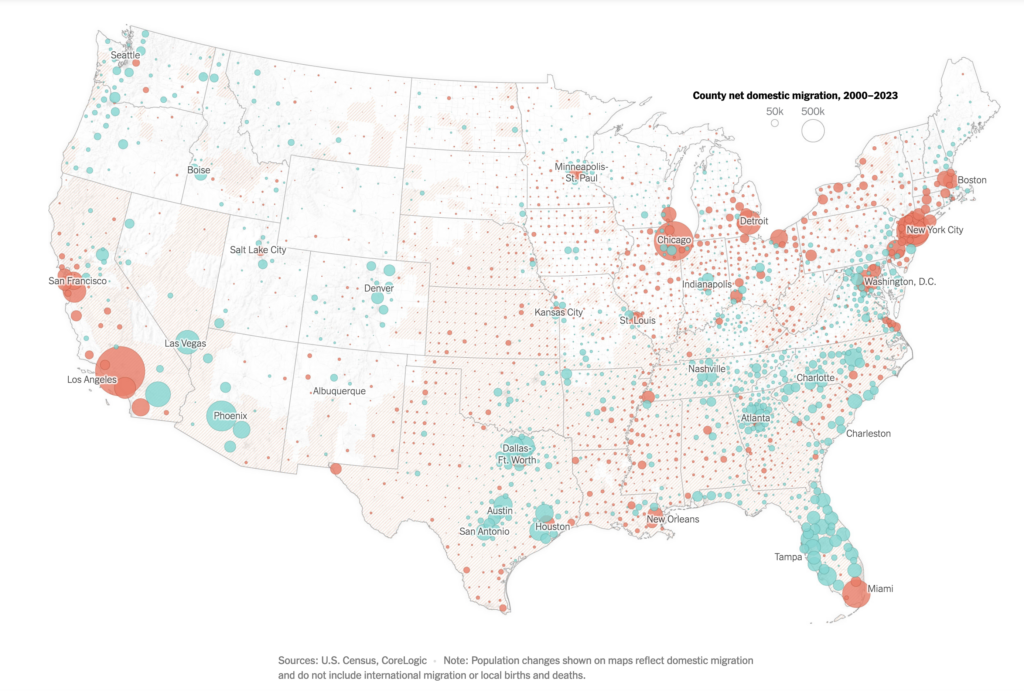

The Times headline is probably provocative but wrong – there are climate safe havens, but moving from the shore to the mountains may not be the reduction of risk you’d hope it would be. Many of the safer locations to mitigate climate risk are in the Great Lakes region, an area that’s been losing population for decades. Indeed, over the past decades, Americans have continued fleeing safer locations and moving towards more brittle and vulnerable ones in the south and west.

Americans have migrated from north to south in great numbers, increasing the population in cities vulernable to wind, flood and heat risk that increases with climate change.

Abrahm Lustgarden, a climate reporter for ProPublica, wrote an excellent book called On the Move about climate-based migration, in the US and globally. Lustgarden’s personal decisionmaking informs the story: he lives in a wildfire-prone part of California, keeps a “go bag” packed at all times in case his family needs to flee, and intersperses his own questions about whether it’s time to migrate with his interviews throughout the book. In the wake of Helene, he notes that we might finally be seeing evidence that at-risk communities might lose population in the near future. The evidence is subtle and complex: it doesn’t mean we’re seeing the abandonment of cities like Tampa, but that growth in the most vulnerable areas may be 2-7% below where it would have been if these communities were not experiencing significant climate risk. But it can be really hard to see those patterns against a 70 year pattern of Americans moving from the Northeast and Midwest to the South and West and a more recent pattern of moving from central cities to suburbs and exurbs in search of more affordable housing.

If we do see cities like Tampa start to lose population – at first by growing more slowly – Lustgarden predicts we’ll see the wealthiest and most flexible move first, with the poor and elderly left behind. This could lead to a “death spiral” for cities, with fewer taxpayers left to fund essential infrastructures and services. So not only are our infrastructures not built for this, but we may be facing cities that aren’t built to fund this.

I found the fifth episode of Not Built For This to be the most powerful and memorable. It was, I suspect, meant to be the “good news” episode – it’s the story of how Hamilton City, CA, a small community of Latino farmworkers located outside of Chico, finally got a levee to protect their homes. And while it’s a moving story with funny elements – a local fundraising event that became famous for its homemade tamales is a recurring theme of the episode – it’s basically a twenty year story of government bureaucracy failing to protect vulnerable people, until it finally did. My takeaway: if it requires twenty years of tamale-fueled fundraisers to get sufficient money for a poor community to build a levee, we’re all screwed. Not only is our country not built for this, but its processes are too slow and onerous to react to an interlocking set of crises that are unfolding faster than we expected.

Hurricane Helene has already become highly politicized, thanks in part to a wave of disinformation from right-leaning news sources anxious to shift blame for slow hurricane recovery to the favorite target of undocumented immigrants. (The conspiracy theory holds that FEMA is running out of money to help flood victims because they’ve overspent on resettling undocumented immigrants in the hopes of securing democratic votes. It’s not true – while FEMA has been helping resettle immigrants, in part because of stunts by red state governors bussing migrants to blue states, FEMA is not out of money.) Milton seems likely to affect Florida (with a vocal pro-Trump governor) and the swing states of Georgia and North Carolina, and how these states recover from hurricane damage may affect the 2024 election. But once that smoke clears, we need – as a nation – to have a broader conversation about where and how we live.

we won’t do much to help people get out of bad situations, you can see how we have abandoned so many people in dying rural towns (as with everything else made worse by climate change) with no easy/viable exit available and the feds and market-makers/corporations no longer need them in those areas. Their schools and hospitals are doomed, grocery stores leaving, churches closing, and there is no help coming….