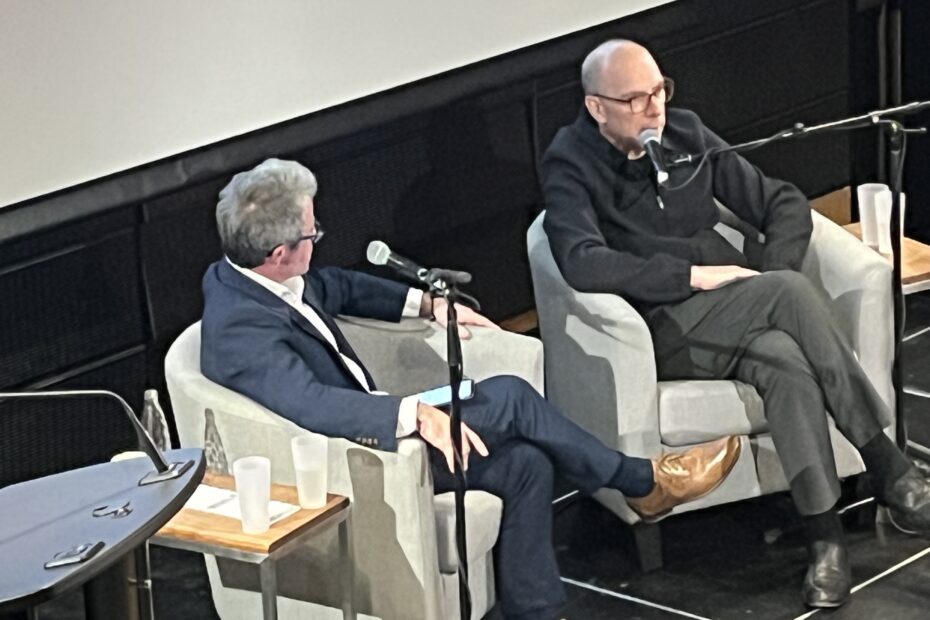

Jay Rosen and Taylor Owen close out the first day of “Attention: Freedom, Interrupted”, in a live taping of a podcast (Machines Like Us) for the Globe and Mail. The topic is the evolution and collapse of journalism in democratic societies… and it would hard to imagine a better pair of conversants for this topic. Jay teaches at NYU and writes a legendary blog called Press Think, and Taylor is a wonderfully talented media scholar who leads one of the best labs studying online spaces.

Taylor’s intro talks about the collapsing trust in the media in Canada and the US, the closure of many local news outlets, and the shift of trust from journalists to influencers, like Joe Rogan. He asks, “How do we make our way out of this strange post-truth moment?”

Asked to describe the problem journalism is facing, Jay quips, “The problem is there’s so many problems.” We’ve lost enormous headcount within journalism, as much as 77% of spending in US newsrooms. Journalism is much weaker than it was, and the business model problems of journalism have not been solved. While there are exceptions like the New York Times, journalism has been shrinking for thirty years.

Another problem has to do with the authority of the press. The press remains attached to “things there are basically… over.” When you’re producing the world every 24 hours it’s very hard to step back and reset the company, Jay explains. Journalists based their work on a model of politics in which the US had two major parties, which competed every four years, did business similar ways, looked and acted the same way but believed different things. That allowed the press to stand apart from both and provide a balance between the two.

Now that the Republican Party has gone “off the rails in a direction we can call anti-democratic”, it created an asymmetry. The Democratic Party is still a recognizable political party, but the Republicans are not. The press still has not adjusted to this shift. Owen suggests we need to start further back than 2016 to examine the collapse of journalism and the transformation of American politics – Trump is the middle of the story, not the beginning.

Jay got interested in “the savvy style of political journalism” some years ago – it’s a focus on who’s ahead, who are the winners and the losers. Who are the spin doctors and what tactics have them come up with? This journalism appealed to many people in Washington DC, NY and in many state capitols… but it’s enormously alienating to folks who are not interested in politics as a game.

This style is easy, Jay says, and portable – you can take it with you from one election to another. It creates relationships between reporters, spin doctors and campaign staff. Every four years, everyone goes and lives in Iowa together for the primary. The savvy style works for those interested in inside views of politics, but it tears viewers away from their fellow citizens, who have much weaker connections to political processes. The political world covered by the savvy style is so much smaller than what journalists should actually be covering.

Taylor asks Jay about another term he often uses: the view from nowhere. This is a way journalists advertise that they have no alliances, no ideology, and that they are “politically innocent”. You should believe us because we are nothing more than observers of the world. Jay thinks there’s something missing in this view: the ability to connect with the audience. Journalists generate authority with the view from nowhere, but they end up above and disconnected from the needs of their readers. We can understand the principles that led to the view from nowhere, but we can also see how it makes a form of journalism that’s hard for readers to relate to or believe in.

Owen notes that there’s now a feeling that journalism is too subjective. Is part of the solution to move back to the view from nowhere? Jay notes that problems with objectivity are unlikely to be solved by an excess of subjectivity. Instead, journalists should tell us where they’re coming from: that they have values, interests, histories, commitments, like everyone else. This is, in part, what influencers do – they tell us how they look at the world. Journalists still need to commit to high standards of verification, something that influencers don’t need to do. But verification does not mandate the view from nowhere – we don’t need to be robots or gods, we can be embodied individuals with histories, and with high standards for transparency and truth-telling.

How does savvy journalism lead to the Trump moment? Jay suggests we consider “verification in reverse”. Verification gives us confidence in a journalist. But when you take something that’s been verified and raise doubt about it, you raise confusion, argument and attention. That release of energy can power political movements… and that’s how Trump powered his rise to politics, through doubt over Obama’s birth certificate. It didn’t matter to Trump that journalists had verified the certificate by going to the government office in Hawaii – reversing the process of verification generated energy, doubt and attention, the forces that gave his campaign momentum. Owen wonders “Is this the first time we saw reality breaking” the way that Trump so regularly breaks it?

Rosen explains that journalists have no good answer for verification in reverse, without abandoning their commitment to verification. Journalists should have been able to admit to themselves and the public that something new, something we haven’t seen before, was unfolding with Trump. But journalists and the newspapers they were embedded within had strong incentives to hold onto the view from nowhere and the savvy style.

It took the US press four or five years, Jay says, to say that Trump was lying. It shouldn’t have taken that long. In 1976, Gerald Ford was running against Jimmy Carter and said something odd: he said that eastern Bloc countries were not captives of the Soviet Union. People reacted with disbelief – are you denying Soviet influence? Ford tried to explain that he was making a point about the resilience of people in those countries, but the controversy haunted his campaign and may have contributed to his loss. When Trump lost the first time, the fact checker at the Washington Post said that Trump had 30,000 lies and misstatements during his presidency. We’re dealing with a different animal here – Ford made a strange comment, and the whole press system jumped on him for clarification and comment; Trump overwhelmed the system to the point where the regular rules could no longer apply.

Why wasn’t the press able to face Trump for the 2024 campaign, Taylor asks Jay. Reporters needed to become pro-democracy, Jay tell us. But when he told this to newsrooms, reporters said, “You’re asking us to be pro-Biden.” Jay explains that what he meant was that we need some sort of new rule book for this new moment in politics. The danger, if we don’t, is that we lose something more than an audience or an industry – we might lose democracy itself.

The Trump re-election is a repudiation of journalism… but it’s a repudiation of expertise of all sorts: the intelligence community, universities, the civil service, experts of all sorts. “Trump ran against the authority of knowledge itself.” What Americans call “the big lie” – that Trump won the 2020 election – has created a litmus test in which anyone who works with him has to accept this false parallel reality. Those who decide to work with him come up with reasons why they believe the election was stolen. Like in a criminal enterprise where loyalties are reinforced by shared criminality, people connect because they’re implicated in believing a shared lie.

Jay’s dissertation, years back, was about the “public” and the idea of journalism that informs the public. Owen wonders if we’ve lost a public. Jay says, rather, it’s impossible to believe that there is a public.

No one worries that affluent and powerful people won’t have journalism that informants and empowers them – lobbyists who make the healthcare industry run will pay $1000 a month for sophisticated news reporting. The question is whether everyone else is going to be able to have meaningful, verified information – and the current answer is “definitely not”. This takes us from a public to a mass, a de-evolution in who we think the press is serving.

The disparity between information spheres feels like a trap we can’t escape, Taylor observes. When we try to talk about these problems, Jay notes that we end up with terrible abstract terms like “post truth” and “parallel realities”. These are hopelessly elite terms that are also devoid of hope – if we are post-truth, what are we doing talking about a future of journalism or of citizenship?

After Trump’s re-election, Jay decided to take three months off because he realized he didn’t understand how to write and talk about the current situation. This interview is his return to the public sphere, and he admits he still doesn’t know what to do. He’s dropped Twitter, leaving behind 315k followers. He’s now on BlueSky, and trying to figure out a new way of writing. “I don’t want to keep saying what I’ve been saying for forty years.” Blogging was a different way of writing, Jay observes, and social media was a new form of writing as well. We’ve had to learn how to write for new media multiple times.

Taylor notes that Canada is arguing about whether to continue having a public broadcaster. Jay notes that there’s significant research that shows that countries with a public broadcaster do much better at preserving democracy because there’s a common set of facts for citizens to rely on. “Anybody with a public broadcaster that big and influential should feel very fortunate… I think you’re lucky and you would be crazy to ditch it.”

”Institutions like a public broadcaster are large and hard to turn around,” Taylor notes. “And they’re harder to revive,” notes Jay. One of the problems the Democratic Party has in the US is the need to defend institutions, many of which are broken… but you’re not going to fix flawed institutions by burning them down. Trump’s MAGA movement is powered by burning down institutions… “once you realize that, it seems more realistic to have pro-democracy journalism.”

Journalism is a social practice – reporting the news – and Jay believes it will never die, because it’s necessary to modern civilization. But the media and the news business may or may not continue to exist… which is a problem because the media controls flows of attention. The practice of journalism is fundamentally human and will persist, but we need to discover, again and again, how to support it.

Taylor asks whether we should see journalism as a solution to the problem of failing democracy. Jay suggests that we need much, much more for modern democracies to work. Lippmann, in Public Opinion, notes that we can’t expect the press to tell us what’s going on if we don’t have a government that tells us what’s going on. Without basic information, it’s impossible to tell whether the government is doing what it should be. In response to Lippmann, governments created institutions that document labor statistics, other key measures of governmental success… and those statistics are now being destroyed by Trump to bring us back to a world where it was impossible to verify what the government was doing. “In his dinosaur brain, he knows that anything that connects him to accountability has to go.”

Pingback: Destroying Autocracy – 13 March 2025 – Battalion

Pingback: "Post-post-truth", or how the SignalGate story is forking reality - Ethan Zuckerman