Day two of TED closes with the TED Prize, the conference’s annual effort to honor the work of innovators and make it possible for them to expand their impact. Chris Anderson says, “It’s a prize that looks forward and looks backwards.” Winners are allowed to wish for whatever they want, to think big, be creative and not reveal their wishes until this night.

Amy Novogratz, the TED prize director,walks us through some of the past TED Prize winners and their wishes. Ed Burtynsky, who won a prize in 2005, wished for different ways to talk to people about environmental issues. We see the trailer for his new children’s website, “Meet the Greens”, which is designed to get kids to think differently about the environment. We also the the trailer of his forthcoming documentary, “Manufactured Landscapes“, which shows extraordinary panoramas of human-created environmental devestation.

Reviewing 2006’s prizes, we start with Dr. Larry Brilliant – as Amy notes, he’s had a good year. His prize coincided with becoming the director of Google.org and with the resources of Google and TED, he’s got an “early warning network” about medical threats “preparing for launch.” (I wrote in more detail about this earlier today.)

The first prize winner for 2007 is James Nachtwey, a remarkable war photographer who’s been described as a “one man human rights watch”. He’s been extensively honored for his work, winning numerous prizes for his work covering some of the most difficult images in the world.

He apologizes for using notes – “after spending an entire career trying to be invisible” speaking before a group is an “out of body” experience. The truth is, his images are so powerful and moving, I found it very hard to even follow his voice for much of his talk. As he said, “I have been a witness – these pictures are my testimony.”

Nachtwey takes us along his career, starting with his idealistic training in the 1960s. The pictures of the civil rights movement “had a powerful influence on me.

Our leaders were telling us one thing, the photographers were telling us another. I believed the photographers and so did millions of other Americans.” He believed that the consciousness that comes from war photography could “evolve into a shared sense of conscience,” to “give voice to those who otherwise would not have a voice.”

He takes us on a painful journey, starting in Northern Ireland in 1981, photographing street protests and hunger strikes. In the 1980s, he found himself in Central America, tracking the civil war in Guatemala between an indigenous rebellion and a European-descended oligarchy. He photographed the first Intifada and the descruction of the refugee camp in Jenin. He shot the fighting in Bosnia from people’s bedrooms, watching neighbor fight neighbor. A friend led him to a cemetary, saying, “This was once a park. All my friends are here now.”

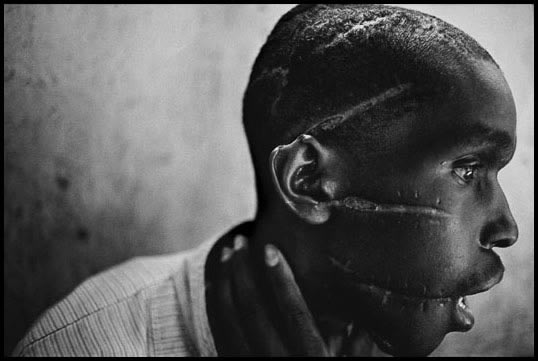

From South Africa, where he photographed the end of apartheid and the election of Nelson Mandela, he went directly to Rwanda – “it was like taking an express elevator to hell.” Showing piles of machetes and a survivor of horrible mutilations, he mentions that somehow Rwanda, like Darfur, didn’t manage to capture the world’s attention to demand coverage.

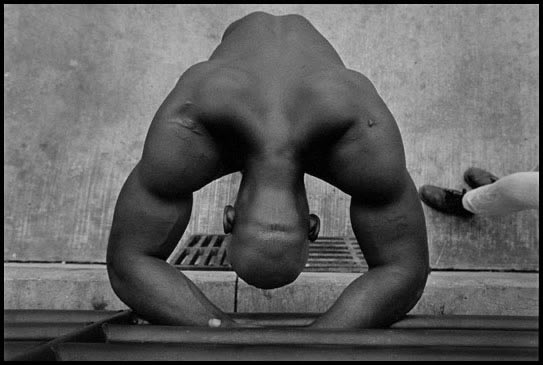

His recent coverage has expanded to social issues: orphanages in Romania, where state policy turned children into a commodity. Dioxin in southeast Asia. HIV in Africa. Homelessness and poverty in Indonesia. Drug addiction in Pakistan. He looks towards our country as well – crime and punishment in America, including powerful photos of life on a chain gang in modern-day Alabama. American troops in Iraq, returing injured from the battlefield and going through recovery.

Nachtwey tells us, “I’m a witness – I want my testimony to be honest and uncensored.” He’s figured out how to channel his anger, “don’t let it cloud your vision.”

His wish is a very simple one: “There’s a vital story that needs to be told.” He wants help gaining access to it, and help coming up with innovative and extciting ways to use news photography in the digial era.

Chris Anderson explains that Nachtwey can’t tell us the specific story he wants to tell for obvious reasons – it’s going to take diplomatic work to get into the country in question and lots of preparatory work. It should be fascinating – and probably profoundly disturbing – to see what story Nachtwey chooses to tell with help from the TED community.

Pingback: Reality, By James Nachtwey at connecting*the*dots

Pingback: Fotografiskt » Blog Archive » James Nachtwey

Pingback: …My heart’s in Accra » Putting a face on XDR-TB

Pingback: Reality, By James Nachtwey | You Are In An Open Field

Comments are closed.