The first time it happened, it was deeply disconcerting. I was sitting in a beautiful garden in suburban Harare in the shade of a flowering tree, chatting with a pair of passionate, committed activists. As we talked about how bad things are in Zimbabwe – a currency collapsing, 80% unemployment, a dysfunctional media, the lack of basic goods like bread and petrol, violent supression of demonstrations a few days earlier – we sipped our coffee, enjoyed the tropical sunshine and cool breeze and watched the children across the garden play with the tortoise ambling between patches of sunshine and shade.

From the statistics I read before coming to the country, I expected Zimbabwe to be a hell on earth. Instead, it’s a very pleasant place to take a vacation. The weirdness of this juxtaposition got less weird with repetition, but still caught my attention every time.

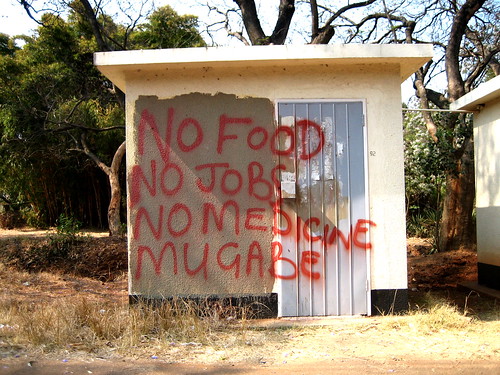

The only graffiti I saw in Harare. According to friends, this building gets bombd every night, repainted each morning.

Talking with my friends in the garden, I told them the story of the woman I sat next to, flying into the country. She’s a doctor, an immigrant to Zimbabwe 20 years ago – an immigrant Zimbabwean, not a Rhodesian who stayed through the transition. Her children are succesful professionals in the US, and she’s torn between continuing to practice in Harare and leaving the country, as so many other medical professionals have. She mentions “the situation” – “it’s horrible, it’s just gotten so bad.” I ask her what’s most difficult for her, what parts of the situation she finds hardest to deal with, and she switches subject, talking about her garden. It’s what we talk about until the plane lands.

I’d assumed that she didn’t want to tell me about her dissatisfaction, worried that I might communicate her dissent to someone in the government. My friends tell me this probably isn’t the case. “Lots of well-off people, who have money outside the country, are locking themselves in gated compounds and tending to their gardens. They’re keeping their heads down, waiting for the situation to pass.”

It’s not ignorance or indifference, my friends argue. It’s exhaustion. Activists are feeling it too: I ask one activist about an online project she’s involved with. The site wasn’t updated for a few weeks and readers around the world began to wonder whether she and others involved had been arrested. “We took a break. We’re so tired. We all needed a holiday.”

It’s easy to understand why the situation is so frustrating for activists. Harrasment of people in “the movement” is relentless. I have a beer with three young activists – one has just been released from central prison where he was held for three nights for distributing leaflets and posters prior to the abortive ZCTU protests on 9/13. I ask him how his family was dealing with his arrest. “They’re used to it,” he tells me. “It happens so often, it’s not really a surprise for them any more. And the lawyers call them.” One of the best organized aspects of the Zimbabwean resistance is the legal profession – groups like Zimbabwean Lawyers for Human Rights organize legal representation for people arrested by the police, alert their families and find medical support for anyone injured in custody.

The local alternative to razor wire. Hard to believe this would fly in South Africa, land of the electric fence.

So why aren’t strikes like the 9/13 event inspiring mass turn-outs? Zimbabweans know how to riot – they turned out in the streets in 1997 and 1999. A friend points out that there was a single figure – Morgan Tsvangirai, head of the ZCTU – who served as a rallying point for the opposition at that time. After losing the 2002 Presidential election as the head of the Movement for Democratic Change and surviving prosecution on two separate treason cases, one would expect Tsvangirai to be a powerful rallying point. But the MDC has split over tactics – whether or not to boycott parliamentary elections – and Tsvangirai was not one of the organizers of the 9/13 event. (Media sympathetic to the government used the disruption of the 9/13 protest as evidence that MDC is weak and disorganized.)

But Zimbabweans may also be avoiding the demonstrations because it’s just so hard to keep their families sheltered and fed. Operation Murambatsvina may have displaced as many as 2.4 million families from their homes; bread shortages are forcing the government to release hard currency to import wheat; petrol shortages make transport so expensive that some people can’t commute to work any more. These privations might inspire revolution in some countries. In Zimbabwe, it inspires people to “make a plan”.

The phrase is said as a single word – “makeaplan” – and reflects the incredible resilience of the Zimbabwean people. Power cuts mean the kids cannot study their books? Send the kids over to one house and light lamps, conserving expensive lamp oil. Can’t afford transport to your village? Trucks leaving Harare stop and load passengers on top of their loads, taking money to help with petrol costs. People who can’t afford prescription medicines – in short supply because of the currency crisis – make friends with people who travel to South Africa, who can smuggle medicines over the border.

Walking into town one morning, trying to find a taxi, I find myself in step with two young men walking to work. They tell me the taxis don’t come by here any more – it uses too much petrol to cruise for passengers – and encourage me to walk for another half an hour, into downtown, where I might find a cab. “It’s good exercise,” they tell me. “Look how strong we’ve become,” they say, laughing.

It’s amazing what you can accomplish by making a plan. My friend Kennedy Mavhumashava talks about a story she recently wrote for a Panos website. Despite AIDS donors deciding to cut programs in Zimbabwe, HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe is falling, both in the adult population and in mother to child transmission. What’s astonishing about this is that Zimbabwe spends much, much less on HIV care than other countries. Well-funded nations like Botswana spend $74 per patient per year – Zimbabwe spends $4. How?

Mavhumashava believes that the success reflects the robust infrastructure built under the Rhodesian government and under the beginning of the Mugabe years. This doesn’t just include roads and buildings – it includes education and training. Zimbabwe’s literacy rate is extremely high. Even with an exodus of doctors, the national health service operates clinics that help keep some of the population alive despite shortages of anti-retrovirals and other drugs.

“Make a plan” allows Zimbabweans to get up every morning, try to go to work and find enough food to survive the next day. But this resilience may mean that Zimbabweans aren’t inclined to take to the streets. Some complain that government ministers are making money on corrupt business deals, but it’s hard to believe that anyone’s getting rich in a country where the overall economy is 30% of what it was five years ago. The bravest ones print leaflets and newspapers, risking imprisonment to express their dissent. It’s hard to know how many people they’re reaching, and what they might be able to inspire people to do.

It feels like everyone’s just waiting for “the old man” to die.

There are an estimated 1.5 million Zimbabwean emigrees in the UK. Add in emigration to the US, Canada, South Africa, and there are 2-3 million “missing” Zimbabweans – a huge number in a country that has a population of under 13 million. Reading the news from Zimbabwe, you can’t help wondering why so many people have stayed.

Walking down Kwame Nkrumah, Harare

But walking down Kwame Nkrumah Avenue in Harare, lined with jacarandas in bloom, I think I understand that this could be a very hard place to leave. Or, as one friend tells me, hugging me goodbye, “I’m not letting that old man chase me out of my home.”

This post is part of the Holiday in Harare series.

Pingback: Graffiti Friday: Reality In Zimbabwe at connecting*the*dots

Covered the war 75-80 and have monitored situation quite closely since. Nevertheless, your despatches are more valuable than you may realise. Best wishes, RC

Pingback: …My heart’s in Accra » Zimbabwe: Where’s the breaking point?

This is the first time I have visited your page and I just love it. I love your writings about our country. Do you see its so beautiful…its a pity.

I know what you mean when you said “From the statistics I read before coming to the country, I expected Zimbabwe to be a hell on earth. Instead, it’s a very pleasant place to take a vacation.”

I visited Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe at around the same time you were in Harare. Climate was great, people were chatty, hotel service was world-class (certainly superior to most developing countries) and immigration was unfailingly courteous, even cracking a few jokes about the current economic instability.

Were it not for the strange bank notes, the menus without prices and the reports in the foreign press you’d almost think it were the perfect country to live in.

Pingback: …My heart’s in Accra » Mugabe makes more Zim millionaires

Wow! That Herare seems like a place that worth visiting.

Comments are closed.