We turned off the snowmobile tracks half a mile back, as they bent to the west and GPS pointed north to our destination. The trackless snow is knee-deep and I’m sweating as we push forward, one heavy footstep after another. 250 feet from destination. We scramble up a ridge, heading towards an outcropping of rocks beside a small stand of pine. 74 feet north by northeast. As we approach the largest of the rocks, the GPS reads “Arriving at destination”. One step ahead of me, Kris kneels down and extracts a box from a cavity behind the boulder. A nine-inch square tupperware container, it’s spray-painted grey and otherwise unmarked. Steam is rising from my gloved hands as I pry the lid off. As I open the cache, the contents of the box glow in the winter sunshine: a logbook, a laminated card and seven rubber duckies.

The ducks have been hand-painted, dressing them in different outfits – policeman, solider, college graduate. The laminated card doesn’t help explain their presence here. But it does explain the box we’ve found: “Congratulations! Intentionally or not, you’ve found a Geocache!” In cheerful, reassuring tones, the note explains to the uninitiated – “muggles”, as they’re known in caching circles – that the box is part of a global game, offers an invitation to participate and politely requests that the cache remain unmoved and unmolested if you choose not to play. We sign and date the logbook with our caching handles and, regretting that we haven’t brought a duck-themed gift to trade, seal the container and carefully stash it in its hiding place.

We’re 300 yards away, slogging through the deep snow towards the next cache before I get the joke. On geocaching.com, where we’ve found the coordinates that started our hunt, this cache is titled “An Odd Cache“. The title of a cache is often a clue to its location – here, it elucidates the payload: a set of odd ducks.

You may wonder what sort of odd duck chooses to hide children’s toys in a remote state forest in western Massachusetts. (Or spends their free time searching for them.) I wonder, too. Geocaching can be both a solitary and social sport. At home, logging the finds we’ve made, I look at the profiles of the folks who’ve recently searched for the caches we found. A family with two small children. A diesel mechanic. A windshield installer. And always “Rocking the Goat”, a retired couple who’ve logged 11,500 finds in the past five years, including 120 in an apparently epic day. I’ve yet to meet any of these people in person, but I’m starting to understand bits of their personalities from their cache descriptions, the clues they offer, the design of their hides.

I don’t know what drove “Kathy & Gary” to haul a box of rubber ducks up a mountainside. The other caches hidden nearby – by the same cacher – are well-made and thoughtfully placed in beautiful locations, but none hint at the whimsy of this hide. I look for something clever to say as I sign the log online, but can’t come up with something pithy to summarize my sense of satisfaction, surprise and wonder. So I write what everyone writes – “TFTC” – thanks for the cache.

One of the most inspiring and infuriating conferences I’ve attended in the past few years was the Metaverse Roadmap Summit, held in Silicon Valley in May 2006. Most of the participants were devotees of virtual worlds, online spaces where what’s possible is governed by not by the laws of physics but by the restrictions of the software. The ability to build interactive spaces without constraints seems to bring out the utopian in many thinkers. Much of the conversation focused on aspirations for technologies that seemed divorced not just from their current state of development but from the wildest hopes of their developers. I was – and remain – unconvinced that (even very technically sophisticated) virtual worlds will automagically encourage intercultural dialog and collaboration or increase empathy. (No need to repeat my rantings here.)

I was more impressed with the thinkers at Metaverse Roadmap who were exploring augmented reality, ways of overlaying layers of information over the real world. Rather than starting with a blank canvas as the virtual worlds folks did, the augmented reality crowd started with satellite photos or camera views of the physical world. It was much easier to judge the success or failure of their work – did layering information on the physical world enable interesting new behaviors? Reveal hidden truths? Or did it obscure what was already visible?

Most augmented reality demos I’ve seen since focus on adding information to physical reality to improve decisionmaking. Patti Maes demonstrated Sixth Sense at TED last year, which involved complex hand gestures that manipulated a “data layer” projected on the world via data goggles. She showed one of her students using the system to enhance his experience of a bookstore by pulling up reviews and ratings for the books on the shelves (and, not coincidently, their prices if delivered via Amazon.com). While this particular application didn’t grab my imagination (why not just shop online?), it wasn’t hard to imagine appealing scenarios. My dream: facial recognition goggles that give me a dossier of information about people I’ve already met, so I never have to struggle to remember someone’s name, job or company again.

Whether we’re using technology fresh out of MIT’s Media Lab or the increasingly ubiquitous smartphone, this form of augmented reality is becoming commonplace. Walking down Ninth Avenue in New York, I can query any number of websites and discover that this sushi bar isn’t as highly rated as the one three block south. Dopplr will tell me which restaurants my well-travelled friends prefer; Foursquare can tell me which coffee shop the wired hipsters are jostling to be mayor of. It’s not hard to imagine an augmented 9th Avenue, with Zagat ratings, Board of Health Warnings and Chowhound tips hovering above each eatery, reducing my risk of ever eating a bad meal.

Many of the ways we talk about augmenting reality focus on reducing risk. By adding information to the bookstore, we reduce the risk that we buy a boring title and overpay for it. Augment the grocery store and we reduce the risk that we buy endangered, unsustainable fish or toxic glass cleaner manufactured by a gay-unfriendly conglomerate. Surrounding ourselves with information online – from authorities, friends, from the crowd – we make decisions in the physical world with increasing assurance that we’re getting the best deal, value or quality.

I worry about a world with less risk. With four stars shining over this trendy sushi bar, will I miss the unrated Uzbek teahouse down the street? Or the admittedly crappy dive bar that becomes a sentimental favorite? In a world rich with information, will I still stumble and explore? I don’t want to go back to a world where I can’t pull up record reviews on Allmusic.com… but I fell in love with music buying $2 cutout LPs in the back room of my local record store, stumbling through a forest of forgettable music to my own passions and tastes.

Geocaching augments reality in a different way. It adds a layer of the magical to the mundane.

There are at least 100 caches hidden within ten miles of my house. I’ve found fewer than 30 of them. Driving to the post office or the grocery store, I pass by them and smile at the secret knowledge I have that my neighbors lack – the specific stone that needs to be moved to reveal the hiding place. How many other stones have secrets hiding under them? What other games are played throughout the world, with secrets hiding in plain sight, invisible to us because we don’t know to look?

If the hides I’ve found make me smile, the ones I’ve searched for and fail to find have a more profound hold on me. There’s a cache hidden on or near the guardrail of a stretch of highway I drive almost every day. I’ve spent two hours, split between half a dozen sessions, looking for the mystery of this cache – the bolt I need to turn, the panel I have to slide, the rock to lift to unpack the mystery. When I drive by this guardrail, it glows pink, just like the trigger points for missions in Grand Theft Auto. I can park the truck, step into the neon glow and start an adventure, or I can drive past and go on with my life.

Enhancing the Berkshires this way invites me to exit my well-trodden paths and explore places I’ve systematically ignored for the past twenty years. I tend to think of my hometown – population 2990 – as a small place. It is, if I describe the locations I visit regularly – a cafe, a bar, a gas station, a sandwich shop. But when you’re looking for a small box hidden in ten square miles of deep woods, the real size of the world is made manifest. It’s small because I drive the same two roads over and over, and too seldom stop to turn over the rocks and look behind the guardrails.

Augmented 9th Avenue promises a world with no unwanted adventures. Geocaching the Berkshires promises an adventure any time I’m willing to bushwhack through the brambles, looking for secrets.

The coordinates point to a junction near the center of my tiny hometown, but the cache description makes clear that there’s a puzzle to solve before I can start hunting. I decipher a pair of messages, each encrypted with a different Caesar cipher and discover the true coordinates – a hillside a mile from town. I park my truck, follow the GPS into the woods and almost immediately discover a rusting 1940s Studebaker pickup, its roof partially caved in, but otherwise remarkably well preserved.

The cache I’m searching for is a “micro”, a size too small to contain little more than a paper log. Micros are often magnetic “hide a key” containers. As I kneel in the snow, poking at the back bumper of the wreck, I realize there are a lot of places to hide a key on the frame of a truck. Hands cold, knees wet, I thought back to the cache description, looking for a clue. The cache’s title implies that the truck is for sale, so I begin to act like a prospective buyer, kicking at the nonexistent tires, climbing in the cab to check the comfort of the rusted spring seat. I lift the hood and poke at the near-pristine engine. The dipstick is still in place and as I pull it from the engine block to check the oil, I find the log in a greasy plastic bag. It’s beautiful.

I live in one of the loveliest parts of the US, replete with rolling mountains, fast-flowing streams, colorful forest and rocky cliffs. To my shame, I too rarely take myself out for hikes, wandering through the woods with no destination in particular. Years ago, I concluded that I was simply lazier than my friends, or less in tune with the ineffable rhythms of nature. Now I think I’m just more teleological.

Invite me for a hike up Greylock, the state’s highest peak – which happens to be in my backyard – and I’ll find an excuse not to go. Tell me that someone’s hidden something halfway up the mountain, in a location that’s probably hard to get to and give me no encouragement other than a set of GPS coordinates and I’m off, dragging as many unwitting friends as I’m able to ensnare along the way. I’m embarrassed that it takes something as silly and arbitrary as signing my name to a log to get me to lace up my boots, but there it is. I need destinations, goals, and it turns out that they’ll shape my behavior even if they’re extremely silly.

The reason to go caching isn’t the rubber ducks or the opportunity to sign a log. It’s the non-zero possibility that something strange, wonderful and serendipitous will happen enroute. Some of us are inclined to wander without a goal in mind – others need goals that encourage us to wander somewhere we wouldn’t normally stray.

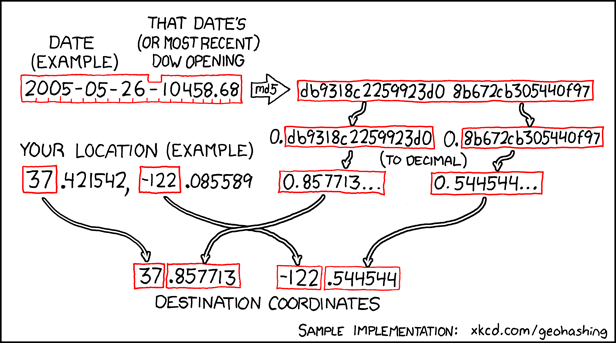

Randall Munroe’s webcomic xkcd has as a central theme the idea that we all need more adventures in our lives. It’s unsurprising then that he invented Geohashing, a strange variant of an already strange game, where a coordinate is generated algorithmically from known, changing values (the date and the previous day’s Dow Jones Industrial Average closing) to generate an arbitrary location within a few dozen miles. (Technically, it generates one per “graticule“, which is the cool kind of word you’ll get to use if you start geocaching.) You’re encouraged to visit the coordinates of the day, and especially encouraged to appear at the coordinates on Saturdays at 4pm local time, when there’s an increased (though still pretty low) chance that someone else will show up.

I love the idea of geohashing – the arbitrary nature of the algorithm has a purity to it that appeals to me. But I haven’t gone to find a hash yet. A cache implies that someone else thought a spot was worthy, in some way, to be encountered and appreciated – a hash has none of that baggage, for better or worse.

I’m interested in building structures that facilitate serendipity, because I worry that I, you and everyone else spends too much time walking familiar paths and too little time wandering in the wilderness. I worry about this in terms of news and information most often, wondering how we find ways to filter the rich information flows of the Internet without filtering out the unfamiliar and provocative. I’ve been making the case that we should stumble into unfamiliar territory because it’s good for us. But that’s about as effective as telling me that I should hike because I’m fat. Perhaps someone (me?) needs to start hiding caches of rubber ducks in strategic corners of the Internet.

I’m in New York City after speaking at a conference and grabbing a beer with Global Voices friends in a nearby bar. I should hurry to Grand Central and catch the next train home, but I’ve got my GPS with me and there’s a cache nearby. I’ve printed out the details and have a theory on the hide. I sheepishly admit to my friends that I’m not going to the subway station with them because I’m going to look for a hidden container somewhere on the mean streets of New York.

My friend Jer wants to come with, and so we follow the GPS across town, to the east. As we walk, I’m explaining my skepticism about urban caching to Jer. It’s hard to hide caches in major cities – unfamiliar boxes tend to freak out police, who might term them “infernal machines” and blow them up. So urban caches are often nanos, stuck to lampposts or the underside of benches. I’m a shy guy – the notion of searching on hands and knees for a tiny metal cylinder in public on city streets makes me nervous.

The cache title makes reference to “the M club” and we find ourselves outside a tony private club whose name starts with M. The clues suggest the cache might be hidden near something of interest to firefighters, and so we begin examining the standpipes set into the side of the building. I feel incredibly conspicuous and wait for the cops to arrive and haul us off for questioning. Finding nothing, we start walking to another corner of the building to check out more pipes. The doorman yells, “Broaden your mind, expand your search.”

Say what? He continues, “Why are you walking away? You’re so close! Persistence!” I ask him for a hint as it’s obvious that he knows what we’re doing and where the cache is. He walks us back to the standpipe we’d been examining. Jer begins unscrewing a cap, something he was reluctant to do while looking over his shoulder for cops. Our zen master doorman objects. “Do you really think they’d put something somewhere the firemen would find it?”

And then I see it – a stray wire hanging over the edge of the metal plate the standpipes are set into. Attached to it, a nano. The doorman congratulates us as I sign the log. Having shared an adventure and a surprise encounter with me, Jer gives me a hug and catches the 1 train. I head towards Grand Central, wondering what secrets, what hidden bits of magic surround me as I walk down 57th Street.

I’d been meaning to try geocaching for a few years now. My friend and colleague Eszter Hargittai convinced me to actually start caching, not by saying anything, but by being so clearly in love with the sport. Eszter is one of the most professional and responsible people I know, so watching her show up late for a Berkman meeting because she’d stopped to seek a cache on the way was the most ringing endorsement of a pastime I can think of.

Kristen Taylor, social media guru and foodblogger extraordinare, made the connection between caching and augmented reality for me. I was trying to convince her to augment her reality by looking for African restaurants in the Bronx and she got me thinking about data layers and structured serendipity instead. Googling for geocaching and augmented reality, I discovered that she wasn’t the first to make the connection – Dan Spira has an excellent blogpost on the topic, which makes the case that exploring the world with GPS doesn’t reduce uncertainty and wonder, but can increase it.

Thanks for the great blog about geocaching. I am also a geocacher with almost 1000 finds and 27 hides to my credit. I’ve also had the opportunity to finds a few geocaches while visiting Zambia, Zimbabwe, and South Africa while traveling there on business. Make sure you bring your GPS next time you travel to Accra.

The first time I played with the LAYAR browser, I thought a geocache waypoints layer would be a really cool addition for augmented reality navigation. I”ve also played with an iPhone app called iSpy which is somewhat similar to goecaching except that a photo is taken, geotagged, and published through the app. Then finders navigate to the location and take a photo which matches the original.

Although I haven’t tried geohashing I’ve solved and found a lot of very difficult “puzzle” geocaches (where one has to solve a puzzle of some sort to obtain the coordinates), including one in Mass. that I solved from, then was the second person to find while traveling through on a vacation.

I like these narrative posts best, I think, Ethan, and congrats on finding the urban cache–I’m ready to start seeking in NY (though I’m planning to come visit what sounds like a trove nearer to you later this spring).

Hereby tapping you as the Easter Egg Hider of the Web, and our conversation made me think further about the importance of precision in devices in the new offline.

Thing about geocaching is that it *seems* at first blush like a solitary activity (kind of like the geek-in-the-basement stereotype that we had to explode), but your examples show expeditions in pairs (and the surprise appearance of that Zen CacheMaster, of course).

I grow wary of thinking about a service like Foursquare only as a database or even a fancy wiki. My favorite place I was mayor of for most of the summer was the Brooklyn Flea, which is a roving event–should there be one static listing with the most current address? multiple listings, one for each location? So far, the users have made multiple listings, but I want my mayoral capital to carry with. Fascinated with how we’ll solve for these (for another long conversation)…

I have been Geocaching for 2 years now. Have 745 cches and 21 hides to my credit. I have google set up to look for geocaching everyday. That is how I stumbled to your blog. I have read many blogs on the subject by newbies and veterans alike. I very rarely post a reply. But with this wonderful description and insight, I just could not pass up the opportunity to say wow. For someone who is a newbie with under 100 finds you have captured the nature of the hobby in which I am addicted to. Thanks. I am going to post this link onto some forums. I would suggest you post this onto the groundspeak forum.

Thanks for the kind words, Todd – perhaps you’ll link to it on Groundspeak on my behalf.

John, iSpy sounds wonderful. I’ll look forward to checking that out.

Kristen, I propose “easter eggs on the web” as our next conversation topic, and hope we get the chance to talk again soon.

Thank you for the article.

You won’t believe how far I read before I realized you were talking about us.

The following is a quote from our 1000 Finds Geocoin.

When we started geocaching we saw it as an outdoor,

hi-tec, something to do.

We never expected the time spent together.

We never expected the hiking.

We never expected seeing new places so close to home.

And most of all:

We never expected the friends we have made.

This is such a beautiful piece, Ethan. In fact, it’s such a compelling piece that my first impulse is to agree with it entirely, but then again, when I think about how I use mobile recommendation apps like Yelp and Dopplr they almost always increase serendipity in my life. The Yelp app for my iPhone has been especially amazing. Two years ago I frequently succumbed to the nasty habit of eating at some corporate food franchise – precisely because it lowered the risk of having a terrible meal.

Sadly there is comfort in expectation, and I know that everytime I enter a Starbucks, Whole Foods, Cosi, or Subway there is something there that will suit me. But the recommendations on Yelp encourage me to hunt out the local, independent joints that I would otherwise never come across. That’s what happened to me last week in New York – the temptation was to head to the always dependable Whole Foods salad bar again. Instead I followed some recommendations from local strangers and discovered a truly incredible teahouse a few frozen blocks away. Information has been good for my serendipity.

Pingback: Complexity and uncertainty « Esko Kilpi on Interactive Value Creation

Oh!!!!!!!!!!!!! I simply loved this. This geocaching newbie is swooning.

Pingback: Desperately Seeking Serendipity » OWNI.eu, News, Augmented

Pingback: Recherche sérendipité désespérement [3/3] » OWNI, News, Augmented

Comments are closed.