Disc One – From the Beatles to British Punk

Intro

Hüsker Dü – “Eight Miles High” (1984)

The Good, the Better and the Ugly

The Beatles – “I Want To Hold Your Hand” (1964)

The Beatles – “A Day in the Life” (1967)

Emerson Lake and Palmer – “Karn Evil 9: 1st Impression, Part 2” (1973)

Proto-Punk

Iggy and the Stooges – “Search and Destroy” (1973)

The Who – “My Generation” (1965)

The MC 5 – “Kick Out the Jams” (1969)

The New York Dolls – “Personality Crisis” (1973)

The Velvet Underground – “Heroin” (1967)

New York Punk

The Ramones – “I Wanna Be Sedated” (1976)

The Ramones – “Blitzkreig Bop” (1976)

The Heartbreakers – “Chinese Rocks” (1976)

Richard Hell and the Voidoids – “Blank Generation” (1977)

Blondie – “Hanging on the Telephone” (1978)

Patti Smith – “Gloria” (1975)

UK Punk

The Sex Pistols – “God Save the Queen” (1977)

The Clash – “London Calling” (1979)

Wire – “1 2 X U” (1977)

The Soft Boys – “(I Wanna Be An) Anglepoise Lamp” (1979)

The Skids – “Into the Valley” (1979)

Disc Two – New Wave and Everything After

New Wave

Talking Heads – “Psycho Killer” (1977)

Devo – “Mongoloid” (1978)

Joy Division – “She’s Lost Control” (1979)

They Might Be Giants – “Ana Ng” (1989)

Hardcore

Black Flag – “TV Party” (1981)

Dead Kennedys – “California Ãœber Alles” (1980)

The Minutemen – “Corona” (1984)

Bad Brains – “Pay to Cum” (1982)

Minor Threat – “Out of Step” (1984)

Minor Threat – “Minor Threat” (1984)

Fugazi – “Waiting Room” (1988)

Post-punk

Wire – “Fragile” (1977)

Gang of Four – “I Found that Essence Rare” (1979)

Mission of Burma – “Secrets” (1984)

Hüsker Dü – “Games” (1985)

Jawbox – “Iodine” (1996)

Jesus and Mary Chain – “Blues from a Gun” (1989)

My Bloody Valentine – “Sometimes” (1991)

Here, There and Everywhere

The Ukranians – “Chekannya” (1994)

The Pogues – “Bottle of Smoke” (1988)

Gogol Bordello – “Punk Rock Paranda” (2002)

And, in conclusion

Mission of Burma – “Einstein’s Day” (1984)

Introduction

So, let’s start with some disclaimers. This isn’t an authoritative or complete picture of punk music. It’s a deeply opinionated, personal view of punk and post-punk, which an emphasis on music I like. Because it’s focused on the stuff I like, lots of “key events” in the history of punk aren’t included, and lots of music many people don’t consider to be punk is included.

Here’s the problem: there are only two bands that everyone will agree are punk bands – the Sex Pistols and the Ramones. You can make the argument that hundreds of other bands are punk, but it will be an argument. Further complicating matters, very few people are genuinely fond of both the Pistols and the Ramones. While I love the Ramones, I had to go out and buy a Sex Pistols album to make this compilation as I, frankly, don’t give a shit about them.

Punk – unambigious, real, classic punk – was a movement that lasted about two years – 1974-1976, more or less. It was more of a musical movement in the US, more of a stylistic movement in the UK (a statement which reveals my lasting love for US punk and my contempt for UK punk.) And both movements are far more important for their influence on the shape of pop music as a whole than for the actual music they produced.

Punk isn’t a style that’s easily defined in musical terms – while the Sex Pistols and the Ramones have some sonic similarities, the music of punk-influenced bands one generation removed includes music as diverse as Elvis Costello and Minor Threat. It’s easier to define punk in terms of ideology:

– Ordinary people should be able to make music.

– Emotion trumps technique.

– Do it yourself, which applies not just to making music, but to touring, promotion, distributing records.

None of which adequately explain why my favorite punk track – Hüsker Dü’s 1984 cover of the Byrds “Eight Miles High” – is quintesentially punk, as there’s a lot of technique to go with the emotion, and very few guitarists can manage quite this much ferocity. I think the simplest way to put it is to say that it’s as far from what the Byrds were trying to do with the song as you can get while simultaneously loving and respecting the source material. The dissafection and dislocation of the Gene Clark lyric is turned into pure, hateful, alienated fury by Bob Mould. My goal isn’t to turn this into your favorite song, though that wouldn’t be a bad thing. Instead, I’m going to try to explain why it’s something I listen to on nearly every plane flight I take, why it’s central to my musical pantheon.

The key to understanding this track is to know that Mould loved the Byrds. He grew up on them, as well as on the Beatles. And the dense, aggressive, fearful music he produced wasn’t supposed to scare people off – he believed he was writing pop songs. That tension between wanted to chase people off and wanting them to love and accept your music carries through all of punk.

The Good, the Better and the Ugly

Whose fault is punk? I blame the Beatles.

It’s difficult in retrospect to remember just how radical the Beatles were, not once, but twice. In 1964, they invented the modern rock star using simple, absurdly catchy pop songs like “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and leveraging the unstoppable power of the screaming teenage girl. Three years later, they released what’s probably the most revolutionary album ever made, “Seargent Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”. Instead of verse-chorus-verse guitar-bass-drums, rock music suddenly involved grand pianos, orchestras and huge, complex arrangements.

It’s difficult in retrospect to remember just how radical the Beatles were, not once, but twice. In 1964, they invented the modern rock star using simple, absurdly catchy pop songs like “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and leveraging the unstoppable power of the screaming teenage girl. Three years later, they released what’s probably the most revolutionary album ever made, “Seargent Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”. Instead of verse-chorus-verse guitar-bass-drums, rock music suddenly involved grand pianos, orchestras and huge, complex arrangements.

“A Day in the Life” is a pair of pop songs knit together with an orchestral climax straight out of Charles Ives – forty classical musicians were instructed to play the full range of their instrument, from lowest to highest notes, within 24 bars. The final chord is played simultaneously on three grand pianos, by McCartney, Martin and a drum roadie for the band, and is followed by an (inaudible) high-frequency tone, then a loop of studio chatter which was placed on the “run-out” groove of the record, where it could repeat endlessly. In other words, this isn’t the sort of music you bang out in your garage, or in the Cavern Club in Liverpool.

The Beatles – and George Martin, their genius producer and arranger – expanded the definition of what could be called “rock music”, and raised the bar for what it meant to be a rock band. Maybe it wasn’t enough to be schoolkids from Liverpool who liked to play guitar. Maybe rock bands needed classical training and complex orchestration.

The early 1970s saw the rise of Progressive Rock – “prog rock” – an attempt to raise the music to a higher level of artistic credibility. This meant complex song structures, compositions that involved formal movements and sections and lots of complex keyboard work. King Crimson, Rush, Yes, Genesis (before Phil Collins took over the band) and Pink Floyd all can be considered prog rock, but there’s no one quite as pretentious as Emerson, Lake and Palmer.

Keith Emerson was a classically trained keyboard player with a burning desire to sound like Jimi Hendrix, if Jimi had been white and had a long metal rod stuck up his rectum. (Oddly enough, Hendrix almost played with Emerson – the two spoke about collaborating, and had Jimi not died so young, they might well have recorded together.) Greg Lake played bass for the band that became King Crimson; Carl Palmer had played drums for “The Crazy World of Arthur Brown”, a 60’s experimental/art rock band.

Their stage shows were an inspiration for the music mockumentary, “This Is Spinal Tap”. They covered Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition” and other classical works, adding epic, noodly keyboard solos. One of their hits had the wonderfully unwieldy title, “Karn Evil 9, 1st Impression, Part 2”, from the album “Brain Salad Surgery”. This track by itself was probably responsible for the formation of hundreds of punk bands. (A common music joke in the early 1970s: “How do you spell ‘pretentious’?” Answer: “E…L…P…”)

The point here: the Beatles could get away with massive orchestral arrangements because they were the Beatles, dammit. Jimi Hendrix could play half hour guitar solos and not bore us to death. But most musicians aren’t Jimi Hendrix, and lots of very tedious music got made by people who thought they were.

Proto-punk

Fortunately, ELP and other prog rockers weren’t the only force in music in the early 1970s. At the same time, bands like Iggy and the Stooges were making nasty, loud, grimy, dirty music that owed very little to the Beatles. If anything, it drew on The Who, whose reputation for debauchery and destruction made them the most dangerous of the “big three” British bands (the other two being the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.) The sort of controlled chaos that ends “My Generation” is a precursor to punk, which for all of its talk about amateurism and spontenaity is, at the end, a form of repeatable performance art. Pete Townshend may have smashed his guitar into his amp at the end of the song as a spontaneous gesture. But eventually, the guitar smash became as much a part of the song as the stuttered vocals. (The stutter, by the way, is a reference to kids on speed and their tendency to stutter – it also allows the “f…f…f…fade away” to sound like “fuck off”, which was about a close as you could get to cursing and still get radio play in the late 1960s.)

Fortunately, ELP and other prog rockers weren’t the only force in music in the early 1970s. At the same time, bands like Iggy and the Stooges were making nasty, loud, grimy, dirty music that owed very little to the Beatles. If anything, it drew on The Who, whose reputation for debauchery and destruction made them the most dangerous of the “big three” British bands (the other two being the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.) The sort of controlled chaos that ends “My Generation” is a precursor to punk, which for all of its talk about amateurism and spontenaity is, at the end, a form of repeatable performance art. Pete Townshend may have smashed his guitar into his amp at the end of the song as a spontaneous gesture. But eventually, the guitar smash became as much a part of the song as the stuttered vocals. (The stutter, by the way, is a reference to kids on speed and their tendency to stutter – it also allows the “f…f…f…fade away” to sound like “fuck off”, which was about a close as you could get to cursing and still get radio play in the late 1960s.)

(Townshend is quoted recently as saying “there were things I could say by smashing a guitar that I couldn’t say with words or music”. He wasn’t the only one in the band whose actions spoke louder than words. Keith Moon, the Who’s drummer, was legendary for his excesses, inventing the popular practice of trashing hotel rooms. Moon died of a drug overdose in 1978, the only major figure in the “big three” to die a classic rock and roll death – remarkably, after ingesting several body weights worth of opiates, Keith Richards is somehow still alive.)

Iggy Pop and the Stooges were masters of this sort of stagecraft – Iggy would routinely smear himself with peanut butter and and launch himself from the stage into the audience – he’s widely credited with inventing stage diving. The on-stage theatrics helped distract from the fact that the band could barely manage three chords. “Search and Destroy”, from “Raw Power”, was produced by David Bowie – his star power couldn’t help the album sell, and despite the fact that it captured the band at its live, shambolic best, the band folded for the first time shortly after its release in 1973. (The Stooges have subsequently reformed several times, recently touring with what’s accurately described as the funniest concert rider in history. In a “punk is a small world” factoid, the bass player for the current iteration of the Stooges is Mike Watt, of Minutemen, who we’ll be meeting in about a dozen more songs…)

The Stooges, in turn, were following in a grand Detroit tradition. The MC5 – short for “the Motor City 5” – were legendary for their fearsome live shows, which can sound as much like anarchist political rallies as concerts. Fred “Sonic” Smith, the guitarist for the band, has at least two claims to be the godfather of punk. The MC5 were, in some ways, the first proto-punk band: loud, nasty, primitive and very, very political. (The band was tightly connected to the White Panther Party, a revolutionary organization founded in response to a suggestion by Huey Newton that white people support the Black Panthers by founding the White Panther Party.) And Fred was husband and muse to Patti Smith, who was the poetess of the New York punk scene, and quite possibly the best lyricist to write punk music.

There’s a sense in which the controlled fury of these Detroit bands is a reference to Altamont, where a free concert in California featuring the Rolling Stones erupted into furious violence. The Stones had hired the Hell’s Angels to provide “security” for the concert, and the Angels ended up busting the heads of many of the concertgoers, resulting in four deaths. One death, that of 18-year old Meredith Hunter, was captured on film, leading to widespread outrage and condemnation of the band’s decision to keep playing. (The Stones, after the fact, say they continued playing to prevent a more serious riot from breaking out.) Altamont, four months after Woodstock, is often seen as the end of the hippie era. Iggy Pop was one of the first of the anti-hippies, a stance popular throughout the punk movement.

Raucous, near-riot Detroit rock wasn’t the only immediate precursor to punk. A group of bands playing in New York were known less for their aggressive presence on stage than for their transgressiveness. The New York Dolls mixed glam rock and the androgny of David Bowie and Mick Jagger with the shambolic intensity of the Stooges. They were cult faves, but no record company would sign them, in part due to their tendency to cross-dress. They weren’t helped much by Malcolm McLaren, the legendary (self) promoter, who attempted to create more controversy by positioning the band as pro-Soviet communists…

The Velvet Underground shared stages (and syringes of heroin) with the Dolls, but their origins were further in the past. Formed in 1965 as a collaboration between John Cale and Lou Reed, the Velvets wrote beautiful, difficult music with gritty, difficult lyrics. Their debut album – a collaboration with European model Nico, produced by Andy Warhol – featured songs about sadomasochism, drug dealing and shooting heroin. Needless to say, tracks like “Heroin” didn’t get a lot of radio play, and the album sold very poorly. But, as Brian Eno noted, while very few people bought the Velvets first album, almost everyone who did formed a band.

New York Punk

It’s against the backdrop of bands like the New York Dolls and the Velvet Underground that the Ramones invented punk. In Forest Hills, Queens, four men donned ripped jeans and leather jackets, changed their last names to Ramone, and started playing simple, stupid bubblegum pop so fast that turned into something strange, aggressive and completely other.

People hated it. Loathed it. Other New York bands, like Television and the Dolls, booed them off the stage in clubs like CBGBs. Part of the difficulty in getting the Ramones was the fact that they could barely play their instruments – the “one two three four” that Dee Dee Ramone yelled before each song was neccesary to keep everyone on the beat. Tommy Ramone wasn’t a drummer – he’d signed on as the band’s manager, but was forced to take his place behind the kit. He ended up inventing a style of drumming that’s completely counterintuitive to anyone trained conventionally – when Mark Bee from the Voidoids took over drums in 1977 (changing his name to “Marky Ramone”), it took him months to unlearn how to play properly and how to play like a Ramone.

People hated it. Loathed it. Other New York bands, like Television and the Dolls, booed them off the stage in clubs like CBGBs. Part of the difficulty in getting the Ramones was the fact that they could barely play their instruments – the “one two three four” that Dee Dee Ramone yelled before each song was neccesary to keep everyone on the beat. Tommy Ramone wasn’t a drummer – he’d signed on as the band’s manager, but was forced to take his place behind the kit. He ended up inventing a style of drumming that’s completely counterintuitive to anyone trained conventionally – when Mark Bee from the Voidoids took over drums in 1977 (changing his name to “Marky Ramone”), it took him months to unlearn how to play properly and how to play like a Ramone.

The band persisted, playing louder and faster, and eventually became home town favorites. They toured the UK in 1976, influencing the first generation of British punk bands and starting nearly 20 years of ceaseless touring. Somewhere in the process, they became respected by their peers for their persistence, relentlessness and uncompromising nature.

The amazing thing about the Ramones is how much their lives sucked. They made very little money from touring and from albums that sold poorly. Almost all had problems with drugs or alcohol. The band members largely hated each other – Joey and Johnny fought over a girl who later became Johnny’s wife. Joey was so hurt by the experience that he wrote the memorable love ballad, “The KKK Took My Baby Away“, which they regularly performed together on tour. Joey and Johnny both died young, both of cancer; Dee Dee had an embarrasing second career as a rapper, then died of a heroin overdose.

But they rocked. And they defined the punk lifestyle – tour incessantly, make the music you want to make even if the public hates it, turn the band into your life. The Ramones also helped invent “band as brand” – one of the unofficial members of the Ramones was graphic designer Arturo Vega, who created the Ramones Presidential Seal, an eagle clutching a baseball bat instead of a sheaf of arrows. Owning a battered Ramones t-shirt with that seal is more or less mandatory for any US-based punk musician.

But they rocked. And they defined the punk lifestyle – tour incessantly, make the music you want to make even if the public hates it, turn the band into your life. The Ramones also helped invent “band as brand” – one of the unofficial members of the Ramones was graphic designer Arturo Vega, who created the Ramones Presidential Seal, an eagle clutching a baseball bat instead of a sheaf of arrows. Owning a battered Ramones t-shirt with that seal is more or less mandatory for any US-based punk musician.

The Ramones were a critical part of a larger New York scene with bands that formed and reformed around the same, core set of musicians. The Heartbreakers were a short-lived group composed of refugees from Television (a much-celebrated proto-punk band that I’ve never really gotten into) and the New York Dolls, united primarily by their fondness for heroin. When Dee Dee Ramone decided he’d write a better drug song than Lou Reed’s Heroin, Richard Hell and the Heartbreakers were the band to record it. (Johnny refused the song for the Ramones on the grounds that it was “too druggy”. This from a band that recorded songs about sniffing glue…)

Hell’s next band, the Voidoids, featured yet more NYC scenesters and left its mark with the wonderfully nihilistic “Blank Generation”, and other classy songs like “Love Comes in Spurts”. With titles like that, you’d assume that punk was a boy’s game – and you’d be wrong. Probably the most commercially succesful band to come out of the NYC punk scene was Blondie, fronted by Debbie Harry. Long before “The Tide Is High” (which helped popularize disco) and “Rapture” (which introduced square white people to rap), Blondie recorded some remarkably fun and edgy punk music, like “Hanging on the Telephone”.

Debbie Harry sold a lot more records, but Patti Smith had the respect of everyone who was anyone in the NYC punk scene. Smith made her way to Manhattan after dropping out of college, giving her baby up for adoption and working on a factory assembly line. She became Robert Maplethorpe’s lover (despite the fact that he was, otherwise, exclusively gay) and began reciting her poetry with guitarist Lenny Kaye providing backing music. Her first single was a cover of “Hey Joe”, which Hendrix made famous a few years earlier, augmented with a strange narrative about kidnapped heiress Patty Hurst. In 1975, she released the first major label album by a NYC punk band: “Horses”. Unlike most contemporaneous albums, “Horses” sounds like it could have been made last week. It’s also got one of the most amazing opening lines of all time on Smith’s reworking of “Gloria”: “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine…”

Debbie Harry sold a lot more records, but Patti Smith had the respect of everyone who was anyone in the NYC punk scene. Smith made her way to Manhattan after dropping out of college, giving her baby up for adoption and working on a factory assembly line. She became Robert Maplethorpe’s lover (despite the fact that he was, otherwise, exclusively gay) and began reciting her poetry with guitarist Lenny Kaye providing backing music. Her first single was a cover of “Hey Joe”, which Hendrix made famous a few years earlier, augmented with a strange narrative about kidnapped heiress Patty Hurst. In 1975, she released the first major label album by a NYC punk band: “Horses”. Unlike most contemporaneous albums, “Horses” sounds like it could have been made last week. It’s also got one of the most amazing opening lines of all time on Smith’s reworking of “Gloria”: “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine…”

(Patti Smith played at MassMoCA years ago, in an open air show in Courtyard C, surrounded on all sides by empty brick buildings, not yet renovated into offices or museum space. She opened with “Dead City”, with the chorus, “This dead city longs to be free”. She replaced one chorus with “This dead city breathes again”, a line which managed to reduce many of the Berkshire people in the audience to tears.)

UK Punk

Punk formed in London roughly a year after it found fertile ground in New York. It was a different beast, almost from day one. New York punk was largely ignored by the press, outside the music trades. Punk in the UK was front-page news, the subject of national debate from almost day one. And that’s Malcolm McLaren’s fault.

McLaren is one of popular music’s great impressarios. At one point or another, he managed the New York Dolls, the Sex Pistols, Adam and the Ants (where he fired Adam) and Bow Wow Wow, where he put a nude 15 year old girl on an album cover. (He also wrote the syrupy British Airways themesong, which plays for hours on end on every one of their goddam planes, which is an excellent reason not to fly BA.)

McLaren built the Sex Pistols out of kids who hung out at his clothing store, “SEX”, on King’s Road, London. The shop had previously sold clothing to “Teddy Boys”, British youth who dressed in Edwardian fashions, until McLaren went to New York and saw Richard Hell. He copied as much of Richard Hell’s style as possible and introduced leather bondage gear to London teens. All that mohawk’d, safety-pinned, anarchy sign bullshit fashion? That was McLaren.

McLaren chose the boys to play in the band, helped rename them (John Lydon became “Johnny Rotten”) and promoted the hell out of them, which meant that EMI signed the band very early in their careers. And Rotten and crew responded to their fame by sneering, angry music designed to piss people off. During the Queen’s silver jubille, the lads released a song titled “God Save the Queen”, a parody of the national anthem which included the couplet, “God Save the Queen / she ain’ no human being”. That, combined with violence on and off stage, outrageous behavior on TV shows and general snottiness, led to the band being banned from Radio 1, the major broadcast outlet in the country.

You couldn’t buy PR like that, not just for the Sex Pistols, but for bands that surrounded them. Siouxsie – later of Siouxsie and the Banshees – became famous as part of the UK scene well before she was famous for her music. And whether or not you know what the Pistols sound like, you’ve probably heard of Sid Vicious. Sid was conclusive evidence that McLaren didn’t care much about the music – he couldn’t play bass, and was so untalented that McLaren had to rehire the old Pistols bass player for recordings only. Sid was a self-destructive heroin addict who may or may not have killed girlfriend Nancy Spungen. He and Rotten clashed, leading to the breakup of the band on their first US tour. Still, their first album is something remarkable, both for songs like “Anarchy in the UK” and for the influence it had on a whole generation of British bands.

Because punk in the UK was more of a fashion sensibility and attitude than musical style, there was much wider range of musical styles represented in the punk movement. The Clash, Britain’s other quintessentially punk band, had neither the distortion or the slop of the Sex Pistols – they actually knew how to play their instruments, borrowed from diverse musical styles, and wrote songs that were musically complex. Joe Strummer and Mick Jones, who shared leadership of the band, were politically passionate and wrote songs about racism, radical politics and imperialism as well as imortal tunes like “Should I Stay or Should I Go”.

At the same time, there was the art punk of Wire, a band that took the speed and intensity of the Sex Pistols and added harmonic complexity and art-school lyrics. The sound that Wire pioneered was so divergent from most British punk that they’re often considered “post punk”, despite the fact that they were contemporaries of the Sex Pistols. While they were pretty weird, they had nothing on the Soft Boys, a truly surreal band founded by Robyn Hitchcock. Their “hit”, “Anglepoise Lamp” is an ode to modernist lighting fixtures… or something like that. Actually, I haven’t a clue what it’s about. I own almost every Robyn Hitchcock album, find him an incredibly smart and moving musician, and am baffled by nearly all of his lyrics. As Nate once asked me, “Does he actually write his songs, or just dream them?”

Those who’ve been subjected to my musical tastes will find “Into the Valley” by The Skids hauntingly familiar. While the album never found much popularity outside the UK, it introduced the world to Scottish guitarist Stuart Adamson, who went on to form Big Country, quite possibly the most underrated band of the 1980s, at least for those of us who like bagpipes.

I’m skipping vast quantities of influential UK punk bands here. First, there were lots and lots and lots of them. Second, many weren’t very good. Third, those that were very good don’t sound much like each other. If you’re tempted to explore, it’s worth listening to Siouxsie and the Banshees, the Buzzcocks, the Jam and Elvis Costello, who is, oddly enough, one of the pillars of the British punk scene. Like I said, it’s a hard scene to characterise.

New Wave

The term “new wave” was intended to refer to a second wave of punk, more electric, more radio-friendly, less angry. The truth is, many of the great New Wave bands were contemoraries of the punk bands, playing the same clubs and sharing the same scene. The Talking Heads were regulars at CBGB’s alongside Patti Smith and the Ramones – in some ways, the band sounded like the polar opposite of the Ramones, all stiffness and tension. They got funkier as the years went by, stealing liberally from James Brown and Fela Kuti, but always retaining a geeky white boy vibe that was unique to David Byrne’s jerky vocal style.

The only reference point for songs like “Psycho Killer” was the even weirder music by Devo, a band formed by art students at Kent State. (The Talking Heads had met as art students at RISD.) “Devo” refered to “de-evolution”, a theory that human beings were actually de-evolving, as evinced by our obvious stupidity and herd behavior. The music parodied conformity, favoring robotic beats and vocals and swirling electronics. “Whip It” is the song that brought them some fame and MTV airplay (as it was one of the first truly great music videos), but “Mongoloid” helps explain just how odd and transgressive the band really was. They’re misunderstood geniuses and Mark Mothersbaugh and “Mutato Muzika” continue to write strange music for TV soundtracks and movies – you’ve heard them, whether you know it or not.

The only reference point for songs like “Psycho Killer” was the even weirder music by Devo, a band formed by art students at Kent State. (The Talking Heads had met as art students at RISD.) “Devo” refered to “de-evolution”, a theory that human beings were actually de-evolving, as evinced by our obvious stupidity and herd behavior. The music parodied conformity, favoring robotic beats and vocals and swirling electronics. “Whip It” is the song that brought them some fame and MTV airplay (as it was one of the first truly great music videos), but “Mongoloid” helps explain just how odd and transgressive the band really was. They’re misunderstood geniuses and Mark Mothersbaugh and “Mutato Muzika” continue to write strange music for TV soundtracks and movies – you’ve heard them, whether you know it or not.

In Britain, the early New Wave movement had a darker and more sinister edge, in part because Joy Division was the lead band in the scene. Named after a section of concentration camps dedicated to prostitution in a supremely dark World War II novel, Joy Division wasn’t exactly the sort of band you listened to for a good time. Ian Curtis, their frontman, suffered from epilepsy, and lived an increasingly difficult existence, plagued by seizures. Before touring to support their first album, “Unknown Pleasures”, Curtis killed himself in his home after sending his wife to her mother’s house and watching Werner Herzog’s “Stroszek”. The remaining members of the band reformed almost immediately as New Order and left almost all vestiges of punk behind.

While New Wave quickly embraced the worst of its cliches – skinny leather ties, weird videos, bad haircuts, Flock of Seagulls – the idea of pairing punk intensity, angular beats and intellectual lyrics survived well beyond the late 70s and early 80s. Anyone who saw They Might Be Giants play live in the 1980s acknowledges them as a punk band – “Ana Ng” is a great example of new wave surrealism ten years after the height of the movement.

Hardcore

While punk became hugely influential on mainstream pop music in the UK, its influence in the US was largely on bands that were deeply underground. Most of the US bands in this movement weren’t signed to major record labels – instead, the bands became their own labels, paying companies to press their records, folding the cardboard sleeves and selling records out of their tour vans or in music magazines.

The pioneers of this movement were Black Flag, an LA band centered around Greg Ginn, an absurdly driven guitarist and businessman. Ginn founded SST, the first great American “indie music” label, named after his ham radio business “Solid State Tuners”. Ginn was a workoholic and Black Flag turned over band members at a ferocious rate, while producing music that was hard, fast and brutal. He finally met his match in Henry Rollins, a middle-class kid from DC whose emotionally abusive father and military schooling left him with lots and lots of anger. Most of the music they produced was vitriolic and often mysogynist – and some was quite funny, like “Wasted” and “TV Party”.

The pioneers of this movement were Black Flag, an LA band centered around Greg Ginn, an absurdly driven guitarist and businessman. Ginn founded SST, the first great American “indie music” label, named after his ham radio business “Solid State Tuners”. Ginn was a workoholic and Black Flag turned over band members at a ferocious rate, while producing music that was hard, fast and brutal. He finally met his match in Henry Rollins, a middle-class kid from DC whose emotionally abusive father and military schooling left him with lots and lots of anger. Most of the music they produced was vitriolic and often mysogynist – and some was quite funny, like “Wasted” and “TV Party”.

Further north in California, the Dead Kennedys were exploring this new style of hardcore punk as a medium for political agitation. Fronted by Jello Biafra (named after the yummy desert and a brutal war in Nigeria), the band sought to provoke with almost every aspect of their existence. (“Dead Kennedys”, Biafra claims, wasn’t intended to insult the Kennedy family, but as a reminder of the “death of the American dream.”) Their 1985 album, Frankenchrist, became the focus of an obscenity suit because it included a poster by HR Giger titled “Penis Landscape“, featuring genitals with and without condoms.

“California Ãœber Alles” is a tyrade against the presidential ambitions of California governor Jerry Brown. Biafra postulates a (theoretical) hippie/fascist state where the “suede denim secret police / they’ve come to claim your uncool niece” No, it doesn’t make much sense, but the chorus “Mellow out or you will pay” is one of the great lines of all time. It’s worth noting the hippie/punk tension – many punks hated the hippies for “selling out” and abandoning their egalitarian philosophies. Beating up hippies (or, more to the point, anyone with long hair) became an article of faith for many punks – I fondly remember hearing Bill Barbot (later guitarist for Jawbox) yell “kill the fucking hippies” when long-haired friend Dave Thomas and I came to one of his early shows in Williamstown… those were the days.

Not all the hardcore bands were quite this intense or crazy. The Minutemen hailed from San Pedro and took great pride in being three guys who were high school friends who liked making music together – they described themselves as “fuckin’ corndogs”. Tragically, D. Boon, their guitarist, died young in a car crash – Mike Watt, their loquacious bass player, has been a major figure in the punk scene for decades, most recently touring with Iggy Pop.

But the California hardcore bands weren’t nearly as hard core as the DC punks. The coolest band in DC in the early 1980s – and quite possibly the coolest band ever to play in that miserable city – was Bad Brains. A jazz fusion and reggae band, they were inspired by NYC punk and decided to start playing reggae very, very fast – “Pay to Cum” is a good example of what resulted. The band released one album and a couple of EPs, but to a certain breed of punk kids, they were the coolest thing ever.

One of those kids was Ian MacKaye, son of a well-to-do DC family. MacKaye is a born leader – not only did lend a hand in founding several DC bands, he founded Dischord Records, which became the main label for east coast Hardcore music. MacKaye was never short on opinions or self-confidence – his influence was at least as much ideological as musical. Because DC bands were formed mostly by kids under 21, the Dischord bands insisted on playing all-ages shows and charging $5 so that tickets would be affordable. A teetotaler, his lyrics in “Out of Step” ended up being read as manifesto: “Don’t smoke / don’t drink / don’t fuck / at least I can fucking think.” A movement of bands began calling themselves “straightedge”, adopting MacKaye’s rules.

Minor Threat, MacKaye’s band, was the best of the hardcore bands, all of which played hard, fast, short songs with declamatory vocals. (The songs are so short that I’m including two, mostly because you might blink and miss the first.) It was an extremely limiting style – listen to a box set of Dischord records and it’s pretty hard to tell one band from another. After Minor Threat dissolved, a Dischord band called “Rites of Spring” managed to shake things up a bit – rather than ranting about Reagan, they started singing about emotions (boredom and loneliness, mostly) and created a new genre – “emo-core”. That term has been tragically corrupted and now mostly applies to bands of whiny boys with eyeshadow who Ian MacKaye would happily beat the crap out of…

Fugazi, Ian MacKaye’s second band, included musicians and inspiration from Rites of Spring, and tried to expand the pallete of hardcore to include funk, reggae and other influences. The result doesn’t sound much like funk to me, but has a great deal more character and depth than hardcore, which I never really connected with. “Waiting Room” is a song that plagued me when I lived in Ghana in 1993 – there were no phones, so any sort of interaction with other people involved hours of waiting, as one of you was bound to be caught in traffic, sick, or otherwise detained. I missed the album so much, I finally wrote my sister and had her send me a copy.

I don’t care much for the Dischord bands, but I include them not only because of their musical influence, but because of the influence they had on my life. Bo Peabody, my business partner at Tripod, was a huge Dischord fan and considered MacKaye to be his personal hero. His decision to found Tripod as a college kid had everything to do with Ian MacKaye’s decision to found a record label, and I’ve been grateful to Bo and Ian ever since.

Post-punk

At Williams, I found myself studying post-modernism well before anyone had bothered to teach me what modernism was. And I fell for post-punk earlier and harder than I’ve ever fallen for punk. Some of the bands in this section – Hüsker Dü and Mission of Burma in particular – are bands that I find myself coming back to again and again as I look for music that moves me.

Post-punk isn’t just music that came after punk – it’s music that reacted to the limitations of punk, fighting against prohibitions against being smart and musically complex. In a very real sense, it was the anti-hardcore, looking for ways to be emotionally intense by expanding the sonic pallete, not limiting it.

Wire was the first post-punk band despite the fact that they were contemporaries with the Sex Pistols. Founded by art students, they made harmonically rich, jagged punk like “Fragile”. In another British art school, Gang of Four was building music on the same model, adding a layer of sharp political commentary on top – “I Found that Essence Rare” starts with a meditation on the bikini and atomic testing on Bikini Atoll.

Across the pond, post-punk was taking root in the US in college towns. In Boston, bassist Clint Conley and Roger Miller found each other after playing in various unmemorable punk outfits. Both wanted to do something stranger, and they auditioned potential drummers by playing “out” music like Sun Ra at extreme volumes until most candidates walked out. One who didn’t was Peter Prescott, whose tastes were similarly experimential. They were a very unusual trio – one where guitar, bass and drummer all wrote songs and sang.

Burma got even more unusual when Martin Swope joined the band. Swope never appeared on stage (until their final performance), but ran their sound board, mixing the shows live. He used an early tape loop system to record part of the mix and then would play the tape back, often backwards or at another speed, as part of the final mix. As a result, Burma shows often had audiences looking around and wondering where the second or third guitar was coming from.

Mission of Burma’s trademark was anthemic pop songs buried in waves of noise, played very, very loud. Listening to Mission of Burma at anything less than 110db misses the real impact of the music – much of the beauty of the sound came from the strange harmonics Miller’s cheap guitar would hit when amplified within an inch of its life. It’s this tendency that broke up Burma, not drugs or interband rivalries – Miller had suffered from tinnitus before Burma, and a few years of touring and recording had aggravated the condition to the point where he constantly heard a chord (middle E, the C# below E and a slightly sharp E below middle C, he told people).

Burma was hugely popular in the Boston underground for the few years of their existence, topping local radio charts, but they never made an impact outside the city. On their farewell tour, they found themselves playing for crowds of less than a dozen. When Miller decided to dissolve the band, there was very little acrimony, and all three principals played together in various avant-garde bands (including the very, very strange Birdsong of the Mesasoic.) Their albums have become far more influential over time, with bands like REM quoting them as a major influence.

Burma re-united for a brief tour in 2004, thrilling fans like me who hadn’t seen them in the early 1980s. (Miller played the tour wearing earplugs, covered by shooter’s ear protectors, and separated from Prescott’s drumkit by a lexan barrier.) And then they surprised the entire world by starting to record and release new material. There’s now more recorded material from the new Burma – two albums – than the old Burma, and it’s damned good, possibly as good as their brilliant 1984 album “Vs.” Burma also has interesting Berkshire connections – Miller plays in the Alloy Orchestra, an ensemble that composes and plays scores for silent films. With Alloy, he’s played MassMoCA dozens of times – when Burma began touring to suppor their new album, The Obliterati, the first tour date was an outdoor show at MassMoCA.

Sure, Mission of Burma was brilliant, unorthodox and inventive. But where’s the drama? The tension? The skeletons in the closet? For that, we’ve got Hüsker Dü. Like Mission of Burma, the Hüskers created walls of noise that mask pop songs. But where Mission of Burma always had a note of restraint to their playing (as well as their touring, recording and life in general), Hüsker Dü went to eleven.

At the core of Hüsker Dü was the tension between guitarist Bob Mould and drummer Grant Hart. Both wrote songs for the band, both were closeted gay men with drug problems, and both hated each others’ guts, at least by the end of the band’s lifespan. (Bassist Greg Norton sometimes described himself as “Switzerland”…) But they packed a lot of great music into a small amount of time, both on stage and on record. At Hüsker Dü shows, the band would move seamlessly from one song to another, rarely giving fans a chance to catch their breath. And in 1984, they recorded three seminal punk albums, going into the studio for the next recording before the previous had even been released.

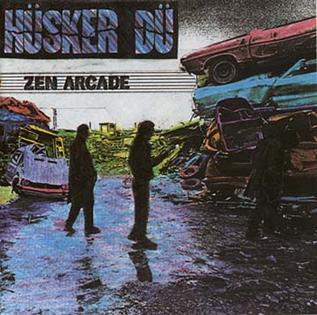

The first of the three, “Zen Arcade”, reinvented American punk music more or less in one fell swoop. (Had anyone outside of Boston actually heard Mission of Burma, it’s possible they would be credited with this reinvention.) Zen Arcade was recognizably hardcore, but involved a wide range of song structures, incorporated acoustic songs as well as walls of electric noise and, most radically, was a two-record concept album, a conceit that shocked the anti-prog rock punk world. (Within months, The Minutemen and others had released double albums as well.) It ended with a fourteen minute squall of noise – “Reoccuring Dreams” – that’s about as far as you could get from 90-second DC hardcore and still remain in the same medium.

The first of the three, “Zen Arcade”, reinvented American punk music more or less in one fell swoop. (Had anyone outside of Boston actually heard Mission of Burma, it’s possible they would be credited with this reinvention.) Zen Arcade was recognizably hardcore, but involved a wide range of song structures, incorporated acoustic songs as well as walls of electric noise and, most radically, was a two-record concept album, a conceit that shocked the anti-prog rock punk world. (Within months, The Minutemen and others had released double albums as well.) It ended with a fourteen minute squall of noise – “Reoccuring Dreams” – that’s about as far as you could get from 90-second DC hardcore and still remain in the same medium.

Zen Arcade raised the bar for what punk music could do. As other bands took up the challenge, Hüsker Dü released two stunningly strong albums – “New Day Rising” and “Flip Your Wig” in rapid succession. (That’s three AMG 5-star albums in a single year, for those keeping track…) The strength of the three albums won the band a contract on Warner Brothers, which gained them even more resentment from the punk scene, as they left indie SST to sign the deal. They released three albums on Warner Brothers, including the excellent “Warehouse: Songs and Stories”, but nothing that challenged their 1984/5 high water mark. The band broke up when Mould – who’d stopped abusing speed and alcohol – and Hart – now thoroughly addicted to heroin, but attemptiong to kick through methadone treatment – could no longer tolerate one another.

It’s hard to find a college rock band from the late 80s, early 90s who doesn’t list Hüsker Dü or Mission of Burma as an influence, but Jawbox is the band most clearly influenced by these early post-punk bands. J. Robbins, who’d been with DC hardcore band Government Issue, founded the band with friends from the local punk scene. Guitarist Bill Barbot (Williams ’90) added a second guitar to the mix and gave Jawbox a richer sound than most trios and quartets – bassist Kim Coletta and drummer Zach Barocas had a more fluid, funky style than most post-punk bands. Robbins wrote most of his lyrics through William Burroughs cut-up method, ensuring that not even he understood what he was singing about. The results were spooky, moody punk songs that deserved a far wider audience than they actually experienced.

Post-punk in the UK was less about speed and more about texture. The seminal band in the scene was The Jesus and Mary Chain, fronted by Jim and William Reid, who wrote simple pop songs buried in waves of guitar distortion. The band’s recordings only capture a fraction of thei assaultive sound they produced live – a high school friend of mine described the optimal listening conditions for a Jesus and Mary Chain concert as “lying on the floor under your seat with your hands clamped over your ears.” The guitar assault largely compensated for the fact that they were one of the rare post-punk bands to use a drum machine. (Again, it’s worth remembering that these guys are more traceable to Joy Division than to the Ramones.)

Kevin Shields, the creative force behind My Bloody Valentine, listened to a lot of Jesus and Mary Chain. MBV balanced their wall of guitars with soft, melodic vocals – the result is something more ethereal than assaultive. “Loveless”, the band’s 1991 masterpiece, spawned a scene in British music called “shoegazer”, referring to the fact that MBV’s members rarely moved on stage and usually seemed to be staring at their shoes, rather than at the audience. “Loveless” took almost two years to record and nearly bankrupted MBV’s record label, but songs like “Sometimes” and “Loomer” represent perfection for a certain flavor of melodic noise.

Here, There and Everywhere

At a certain point – possibly the late 1970s – punk became less of a coherent movement and more a set of attitudes and musical vocabulary that could be applied to multiple styles of music. The Cramps, playing in Sacramento in the late seventies and early 80s, wedded punk to rockabilly, helping create a genre now known as “psychobilly”. The Bad Livers brought punk sensibility to roots folk music, playing upright bass, accordian and banjo in a fashion that was recognizably punk rock at the same time it was bluegrass.

One of the oddest mashups in this space was The Ukranians, who were not Ukranian musicians who discovered punk music, but punk-influenced British musicians – founding members of the band The Wedding Party – who discovered Ukranian music. Guitarist Pete Solowka had developed a habit of playing Ukranian songs he’d learned from his father at Wedding Party soundchecks – as a joke, the band recorded sessions for British DJ John Peel of traditional Ukranian material, adding a violinist and mandolin player. “Chekannya” is a cover of Velvet Underground’s “Venus in Furs”, a marvelously transgressive Lou Reed song about sadomasochism, which includes memorable lines like “Kiss the boots of shiny, shiny leather / shiny leather in the dark / Tongue of thongs, the belt that does await you / Strike, dear mistress, and cure his heart” – sung in Ukranian, the focus (for me, at least) is less on the remarkable lyrics and more on the haunting drone of the melody.

I can forgive Malcolm McLaren because it’s likely that the Pogues would never have existed without the Sex Pistols, and it’s hard for me to imagine a world without the Pogues. Shane McGowan played in a Pistols-knock off band “The Nips” (shortened from “The Nipple Erectors”, before connecting with other Irish expatriates living in London. They took their name from the Gaelic phrase “Pogue Mahone” (which translates, roughly as “Kiss My Ass”) and started playing songs that were both traditional Irish music (featuring banjo, tin whistle and accordian) and punk. They became darlings of the first wave of British punks – Elvis Costello produced their first LP before marrying their bass player Cate O’Riordan, and Joe Stummer of the Clash briefly took over as frontman of the band during one of the (many) periods when Shane McGowan was too drunk to function. (Shane claims to have been drunk continuously for the past thirty years – it’s quite possible that this is true.) There’s a whole brand of Boston punk that’s directly descended from the Pogues, notably the Dropkick Murphys and the dozen hardcore bands they regularly play with.

Eugene Hütz, growing up in Chernoybl, Ukraine, was listening to punk as well, especially to post-punk Einstürzande Neubauten and The Birthday Party, on samisdat cassette tapes. After the nuclear plant meltdown in his hometown, he became a refugee, travelling from Ukraine through Poland, Hungary and Austria, becoming an afficianado of Roma music along the way. When he emigrated to the US, he quickly became a fixture on the New York club scene, DJing parties with an extraordinary mix of multicultural punk and dance music. His band, Gogol Bordello, is evolved from a band that used to play Russian weddings in NYC, and includes an accordian player from the Russian island of Sakhalin, as well as two Israelis and a former Moscow theater director. Their live shows include Brechtian cabaret as well as exuberance which borders on violence – most shows end in a frenzy of plate-smashing, table dancing and general mayhem…

In Closing

It’s hard to know where to end a collection like this. Bands continue to be influenced by punk, for the better and the worse. Bands like Green Day started copying the image and style of punk, but ended up, in an odd twist of fate, emulating some of the political activism and socially-focused songwriting. And the rise of the Internet as an alternative channel for music distribution should help spawn a new generation of musicians who want to go their own way, even if they’re playing geek rock like Jonathan Coulton, and not punk.

The reason I keep listening to this stuff – especially the artier post-punk stuff, is that it’s more interesting than the vast majority of new music released today. I firmly believe that Mission of Burma is still far ahead of their time and probably won’t be fully appreciated until they’re in their sixties. At that point, perhaps they’ll strap their guitars on for a third time and play masterpieces like 1984’s “Einstein’s Day”.

Ethan, have you read Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk? The actual history part would be all old news to you, but you might get a kick out of the ordering of the recollections and the sheer verbal verve on display.

This was a fabulous summary, and I particularly enjoyed the second half, which is where my catalog totally diminishes. I’ve been itching to get some Pogues for a while.

For me punk is mostly about The Clash, and that tradition of jump-jump political anger. A couple of new bands I enjoy in along those lines: RadioOne and Anti-Flag.