Saturday, May 7, 2005

4 posts, enroute and in Tokyo

Perhaps there’s something good about a 6AM flight, but you haven’t discovered it yet. A 7AM flight and you’re up a bit before five, which feels very responsible. Like you’re a go-getter, ready to jump into the day hours before everyone else.

But quarter of four is still night. Instead of a glow in the edge of the sky, there’s night-black, a splash of stars. NPR isn’t on the radio yet – BBC has an hour of election coverage, Blair’s victory making you as tired as lack of sleep. The roads are empty, but Albany Airport is full. The first flight heads to Rutland at 5:15am, and you wonder who needs to be in Rutland by the break of day.

And now it’s Detroit. 8AM, the good restaurants are full, the line at Starbucks is long enough for you to miss your plane. Sit down at a table, wait fifteen minutes for a waitress or a cup of coffee. Give up, Burger King. The WiFi doesn’t work and your bag looks as ungainly and awkward as you feel and keeps tipping over. It knocks into a guy pouring cream in his coffee and you apologize, not awake enough yet to meet his eyes.

So you seek out the fountain, the pilgrimage spot for the lost Northwest Traveler. The water leaps like birds in flight, arcing like an Airbus cutting Great Circles above the Pacific. You clutch a quarter in your hand, say a wish for smooth travel, for safe returns, for luck navigating a strange city, for the people you left at home, still in bed. You let the quarter fly, turn the corner and it’s on to San Francisco. It’s time to wake up.

Never ask for upgrades, either from the gods or from the gate attendants. It’s better to let the karma flow, to naturally find its own level. If you hope for an upgrade, you’ll be disappointed. Better to be desireless, accept what the universe hands you. And suddenly 18-G becomes 5-G and you’re in a seat that turns into a bed, juggling the disposeable slippers, toiletry kit, dinner menu and warm towel the stewardess has handed you. At this point, it’s appropriate to be grateful. And remember to throw another quarter in the fountain on the return trip.

How long does it take to get from Lanesboro, MA to Tokyo, Japan? Precisely 24 hours, as it turns out. It’s Saturday, 4:54 PM – which is to say, Saturday, 3:54AM, the time I left the house yesterday – and I’m waiting for the Narita Express, which goes from the airport to the central railway station. From there, I’m not really sure what to do. The subway station closest to my hotel doesn’t appear to connect to Tokyo station in any meaningful way. Another – which does connect to Tokyo – is a “seven minute walk”. All of which is well and good, but I have no idea what direction to walk in. I keep looking at train station kiosks, hoping to find a “tourist map” which will allow me to get my bearings. The goal – get as close as I can before breaking down and taking a taxi… or asking policemen for directions, which seems to be what Lonely Planet reccomends.

I’m used to being lost in strange places where few people speak my language. I’m much less used to being lost in strange, high-tech places like this. It’s a little alienating… which is to say, I feel deeply alien, like I’ve landed on another planet and am trying – and failing – to blend in.

My goals for the day are simple ones. Navigate train system to get from airport to Tamachi Railway Station. Check. Find map and navigate streets to hotel. Check. (Railway stations have excellent bilingual maps outside them. And it does turn out to be precisely seven minutes walk.) Check in, unpack, shower, get online. Check. Find dinner…

It’s a rule of mine – and many other people I know who gridskip the way I do – that you never eat dinner at the hotel. It’s cheating. Breakfast is fine. But you’re an explorer, and dinner is the key time to explore. So now the question is whether, 28 hours into this day, I can get clothes on, find a restaurant that doesn’t look too intimidating and successfully order dinner. Cross your fingers for me.

Sunday, May 8th, 2005

morning in harajuku

It’s not nearly as hard as it looks.

Once you realize that any transaction can be satisfactorily completed by grunting, pointing and proferring money, Japan gets a lot easier. (And since you’re just here as a tourist, for a few days, almost every interaction will be a transaction.) It sounds difficult, mostly because every transaction seems to offer a long, ritualized patter. But as your role in that interaction is limited to proferring cash, it’s really uncomplicated.

And, on those rare moments when you’re able to offer a phrase of guidebook Japanese – “That meal was a real feast!” – you’re rewarded with a flurry of extremely satisfying incomprehensible dialog.

I’ve now succesfully ordered three meals, using the point and grunt method – four, if you count the brief stop in the McDonalds to enjoy an order of Fish McDippers, and the cafe-style seating overlooking Omote-Sando. What I’ve yet to figure out is how to order enough food to actually qualify as a meal. Last night’s ramen was glorious, but a second bowl, or a bowl of rice, might have made it an actual meal. C., an artist friend who spends a great deal of time in Japan, warned me about this – “It makes you realize how big portions are in the US.” She pauses for a moment. “You’re probably going to starve.”

The solution seems to be convenience stores. They’re filled with bowls of hydratable noodles, oddly-filled sandwiches, and my new favorite food, rice balls. Plus, you can read labels, which has helped me learn that “Black Coffee” – offered in cans from vending machines on nearly every corner – is genuinely black, unsweetened coffee. I’m now excited to purchase some tomorrow morning so I can see whether the cans are self-heating, or come from the machine hot.

Walking the tree-lined gravel path to Meiji Jingu, a shinto shrine in Harajuku, I suddenly hear Nintendo music. It’s the “train arriving” song, a couple bars of cheerful eight-bit electronica, from the railway station, hidden by a thick forest, but actually about 50 meters through the trees. It stops, and the caws of crows and the soft crunch of gravel underfoot is audible again. And then the “train departing” song. And so on, as we make our way to the shrine – a young woman in a kimono, half a dozen hipsters in shaggy haircuts and perfect suits, ties undone just so, a family with matching umbrellas.

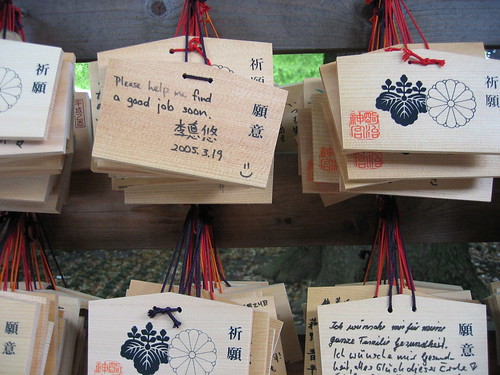

I have an inauspicious temple experience. I don’t find the ritual fountain until after I’ve prayed, so I purify myself as I’m heading out into the wider world from the sacred space, surely a liminal no-no. And while I get the coin – bow – handclap thing right, I miss the final bow, leaving me feeling ritually inept. To top it off, I get the following fortune – a poem by Emperor Meiji – from the souvenier stand when I offer my hundred yen coin and take my scroll:

We shall fall behind

Our fellows in the world

If, when we should advance,

We make no move at all.

Not the sort of fortune that makes you want to linger.

I snap photos throughout, buying a 1000 yen wedding charm for friends getting married next weekend… but mostly so I can take a photo of the charms for sale. 800 yen for safe driving, 1500 for recovery from illness, 700 to attract a spouse. This turns out to be the one place photography is forbidden. I guess some rituals are just too sacred to be documented…

Walking in the side streets of Harajuku, I realize that I have never been, and will never be, as stylish as the kids in Tokyo. Outfits are surreally complex, clearly layered with meanings I can’t pretend to understand. I’m looking for great Engrish t-shirts (so far today “A reality-based t-shirt”; “Sarcastic T-shirts”; “Qestion the fashion”) until I discover they’re roughly $30 and wouldn’t have fit the 12 year old version of me, never mind today’s model.

The only clothing that appears reasonably affordable are the antique kimonos for sale on the corner – they’re $5 to $20, which explains why N. brought so many as gifts the last time they’re here. I remember that I’ve never seen R or I wear the ones he brought and resist buying more. (More to the point, the long one with the blue flowers – the only one I really wanted – gets bought by the Italian woman.)

Each shop caters to a subculture I hardly knew existed. Downstairs, a kid with blond-dyed hair plays with a 15″ powerbook as I check out his wares – t-shirts, throw pillows, beer cozys and action figures, all featuring improbably-breasted redneck women, ala R Crumb in the deep South. Next door, there’s California ska playing, and a selection of fastidiously embroidered sateen jackets. The only black guy I’ve seen is standing outside “Ill” – evidently, a living billboard for hip hop authenticity.

I understand why A. loves this city so much when I find a store that stocks nothing but the funky, patterned button-down shirts he wears. He’s tiny, so they’d fit him, and he works at Google, so he could probably afford to buy them. I’m huge, and pretending to be an academic, so it’s time to go back to the hotel and write a powerpoint presentation instead of indulging in sartorial excess.

The morning’s photos are available on Flickr.

Monday, May 9th

10:37 pm

Three for three. Not a bad record for the day.

Mission one: The fish market.

My guide to Tokyo lists the Tsujiki Fish Market as their main “must-see”. It’s a bit challenging, in a sense – the market’s only open until 8am, so you need to be out of bed and on a train before most of Tokyo starts its commute. Fortunately jetlag – the little of it I have – makes this easy. I’m exhausted by 8pm, in bed by 10 and up by 5:30… which isn’t bad, considering I haven’t taken a sleeping pill yet on the trip.

Out of the hotel at 6:30, two rice balls and coffee in a can. (Unsweetened, cold, black coffee? How did you know, Tokyo? That’s one of my favorite beverages!) I’m on the subway for the first time. It’s dirtier than the above-ground trains I’ve been taking everywhere, and feels more urban, somehow more real than yesterday’s Tokyo, which seemed freshly scrubbed.

The main obstacle in finding the fish market is the decoy markets set up outside. The first one occupies me for fifteen minutes – dried kelp, fresh produce, trays filled with fish. But it’s too neat and filled with tourists, being led around in small groups by guides who narrate stories of knife technique, blowfish poisoning and burdick root.

I change tactics and start tailing a pair of Japanese tourists. (I can tell they’re tourists because they’re not wearing knee-high rubber boots, as everyone else is. Several guys are wearing suits, ties and rubber boots. If I ever unpack fish for a living, I guarantee I will not wear a suit while I do it.) They pass a stretch of road that looks like 10th avenue in New York City – the first gas station I’ve seen in Tokyo, people wearing baseball caps and workclothes… They duck into the bottom floor of what appears to be a parking garage, and I follow, keeping pace, blending in as well as I possibly can, as a tall white guy in Japan.

The second market is grimier than the first – tiny sushi counters, cigarette stalls, knife sharpeners honing blades on a sequence of whetstones. The ground concrete, textured with circles scratched into it. Everything is moist and smelly. I’m closing in on the target.

The main obstacle seems to be a series of small trucks. They have a flatbed in the back, a two-foot wide cylinder in front with a giant wheel on it. They turn on a dime, the wheel rotating the whole front of the vehicle, and they’re speeding past in criss-crossing patterns. Complicating matters are men on motorbikes, pushing hand carts and generally moving as fast and purposefully as possible. I take cover behind a group of parked carts, snap a few photos while I’m safe from collisions, and plunge into the fray.

As long as I follow the flow of traffic, it’s almost effortless. I flow 100 meters past my target, reverse direction and join the counterflow, jumping out in time to clamber up a concrete wall where tekka-sensei, watching over frozen, headless tuna, advises me “Central market. Go.”

I do. The market is an amazing meeting place between Japanese order and developing world chaos. Perhaps a hundred meters on a side, roughly in a ten by ten grid, each square is filled with a dozen stalls. Six different types of octopus at one; bloody vats of eels; wooden barrels filled with baitfish, still swimming; vast sides of tuna, beef-red. Buckets of clams, oysters, sea urchin. Live tiger prawns. I stop to talk to a tuna dealer, trying to make conversation with my knowledge of sushi terms: Tekka? Toro? It doesn’t get me very far. “You buy?” I shake my head. He turns away.

I shoot photographs like a sniper, waiting for my targets to turn away. I take cover from the traffic behind barrels, leaning on posts, camoflaughed behind tanks. Suddenly, there are other Americans. Have they followed me? Or just read the same guidebook? I beat a hasty retreat, out to the decoy market. (I briefly consider breakfasting in the inner market, but am discouraged by a sign that reads: “Please, no English. Japanese only. No sushi. No nudle.”

I have the best tekka don of my life at the counter of a spacious, friendly bar where I make friends by ordering tea in Japanese. (It seems like a better idea at 7:30am than beer, which is offered to me.) I scrape the bowl clean, drink three cups of green tea, and leave, mission completed.

For bonus points, I stop by the nearby Buddhist temple. It’s easier than the Shinto shrines – bow, coin, burn incense, pray, bow. I execute the ritual, then spend a white thinking how similar the buidlign is to an urban church anywhere in the world. Scattered in the movie-theatre style seats throughout the body of the building are people who evidently don’t have other options for where to sleep. I can’t imagine homeless people at yesterday’s Shinto shrine and am grateful for the Buddah’s infinite compassion.

Mission two: The hat.

JP, my boss, has a three year old son, Jack. Jack is a Red Sox fan and fell in love (as only three year old baseball fans can) with a backup outfielder for the Sox. Said outfielder was cut and found himself playing for the Yomimuri Giants. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to locate and purchase a children’s size Yomimuri Giants hat.

(Accept the challenge. JP’s a great guy, and any excuse to encounter baseball culture in a foreign land is a welcome distraction.)

I check out of the hotel and get advice on completing the mission. “Department store?” I ask, pointing to my Red Sox hat, thinking how I might solve this problem in an American city. The woman is intrigued, but skeptical. “You should go to Tokyo Dome”. The home of the Giants, it’s the wrong way from where I’m going, but on the right train line, which makes it closer than something in the right direction but on the wrong line.

I refuel at the best noodle bar in the world. For the curious, it’s just outside of the entrances to Mita subway station, tucked under a pedestrian overpass. Rather than menus, ordering and the other complications of language, there’s a ticket machine in the corner. You insert a 1000 yen bill into the slot, press the buttons – helpfully marked with pictures of bowls of soup and dumplings – and receive tickets for your meal. A cheerful young woman observes the food you’ve ordered and yells the details out to the two chefs behind the counter. (This is curiously unautomated, but very pleasant.)

The best noodle lunch in the world is a bowl of ramen, in thin, meaty broth with a shaving of scallions, some tender brown mushrooms, half a soy-dyed hard boiled egg, and two slices of roast pork. Eat it with steamed shumai and a sequence of glasses of cold wheat tea.

The ride to the Tokyo Dome is a trivial degree of difficulty, complicated only by my roller bag. (Because missions must be played in sequence, and because luggage is neccesary for mission 4: Hotel in Chiba, I’m carrying all my worldly goods with me. One train to Akihabara – the “electric city” beloved of geeks worldwide, where every store sells electronics, hentai or both – another to the dome, and I’m off, climbing an endless sequence of stairs to the stadium, roller bag bouncing behind.

I confirm that there is a gaijin outfielder named “Gabe” playing for the Giants and conclude that I must have the right team. I memorize the Giants logo – not unlike memorizing enough kanji to let me read subway signs – and look for roaving souvenier vendors. There are none, of course. The only people who sell things on the streets in Tokyo are vending machines, and none of them dispenses hats. A circumnavigation of the stadium finds Major Leage Baseball shop, a store that sells goods from the US major leagues… and, basically, nothing connected to Japanese baseball. Tucked in a corner away from all the Ichiro gear is a small stack of Giants gear. I buy a kid’s sized hat for 2200 yen and victory is mine.

Mission three: Sumo!

I send a casual note to Andrew, who loves Japan. “As it turns out, I’m here in time for the May basho. Might just catch a match or two.”

His answer is immediate, and to the point: “Oh. My. God. Asashoryu. It just feels good to say that word.”

Asashoryu is the best sumo wrestler in the world. He’s a twenty-four year old kid from Mongolia, and he badly bruised some Japanese egos when he stormed through the ranks of suno, rising from rank beginner to Yokozuna, the highest rank a sumo can achieve, in just three years. Japan briefly responded by capping the number of Mongolians who could compete in the sport, hoping to stem the tide of foreign competition. They’ve abandoned this now, and the top ranks of Japanese sumo now include a Russian, a Georgian, a Bulgarian, and half a dozen Mongolians.

(Generally speaking, the Eastern Europeans suck. The Mongolians, on the other hand, rock. This is largely explained by the fact that Mongolian males wrestle at every possible opportunity. At picnics, during bar brawls, during the Nandan festival. This is very much in their blood.)

As you may have guessed, I like sumo. A lot. Enough that there’s a section of my Mozilla bookmarks dedicated to the sport. I watch matches online via streaming video. I can tell you the approximate weight and height of half a dozen of my favorite wrestlers. I know roughly when and where Asashoryu was born.

Judo, to which sumo is closely related, was the aspect of karate I was always best at. There’s something deeply satisfying about pushing someone else around. (My favorite workout, to this day, involves pushing my truck – in neutral – around the top of my driveway.) It’s a big guy thing, I think. Kids of a certain size get into fights, where someone roughly the same size tries to shove you over. I always won those fights. In America, guys like me become offensive linemen. In Asia, they become rishiki – sumo wrestlers.

When my trip to Japan aligned with the May basho, it seemed like fate. I tried to buy tickets for the second day of matches over the Internet, but was thwarted by my failure to speak Japanese. I asked the concierge at my hotel and got a great set of raised eyebrows. “Sumo?” Once I convinced him I wasn’t joking, and gave him the number for the sumo hall, he made the call and responded with some odd news: they don’t single tickets in advance, only two or more. “Try the… how do you say it… convenience store.”

Convenience store? “You mean, like Lawson’s?” Evidently, the ubiquitous Lawson’s convenience stores sell plastic-wrapped rice balls, sake in pull-off tab jars, women’s underwear… and sumo tickets. But as the staff of these stores don’t speak any English, this seems like a losing strategy.

So I take the yellow JR train from the Tokyo Dome to the Ryogukan sumo hall. I’ve carefully saved a 500 yen coin for the coin lockers that grace every Japanese public space… except this particular train station. So I lug the rolling bag past a statue of idealized rishiki locked in a stone grasp, across the street, past the middle aged woman who is greeting incoming wrestlers with a song and a flowered wreath. I’m walking next to a trio of sumo wrestlers. They’re wearing white and blue robes, wooden sandals and carrying bags that look suspiciously like ladies purses.

They’re not that big. I could take ’em. Well, maybe one of them. If I caught him by surprise.

The block leading to the arena is lined with a police barrier. Behind it is a very polite group of middle aged Japanese, who applaud politely when rishiki walk past. To the right, the fence around the arena is adorned with colorful cloth banners, each with the name of a wrestler who is fighting today.

I pay 4900 yen – roughly fifty bucks – for a ticket. As I wheel in my luggage, a sequence of people thrust sumo paraphenalia at me – the card of today’s matches, an English-language guide to sumo, a translucent plastic folder adorned with the smiling bulk that is Asashoryu.

I’m early. And my seat is fantastic. In the middle of the balcony, in the center of the “main” side of the ring – i.e., the side the wrestlers face when they square off. It’s early enough that we’re seeing the bouts before the Juryo – junior – ranks. Two rows in front of me is an American family – three stunningly uninterested and one clearly a sumo fan. The sumo fan turns to the older woman – his mother, perhaps – and says, “You can go to sleep if you want, but we’re not leaving.”

I ask the enthusiastic guy to watch my bag and head downstairs to shop. A bottle of water, a can of beer. Two miniature banners that read, in Japanese, Asashoryu, one for A, one for our house. A deck of cards featuring current sumo stars. It’s a good haul.

At 2:45, the juryo ranks enter the hall. The west wrestlers, then the east wrestlers, process onto the ring and make a circle, facing the audience. They’re resplendent in colorful aprons, and they enter the ring to a single “clank” of two wooden blocks.

And then they fight. The matches are very fast, and very, very good. I’m not a good enough fan to understand why these guys are wrestling in sumo’s B-league – they look powerful, balanced and extremely graceful. Very few people are watching, but the stands slowly fill. Suddenly, twenty young Japanese professionals, all in suits, all wearing press badges, march in and occupy the two rows to my left. They’re carrying cameras, videocameras, tripods, microphones, and a laptop. A young woman – who I recognize as “attractive” for a certain Japanese value of attractive that I don’t understand or share – seems to be the center of attention. She’s surfing a website – livesumotv.com – in what seems to be an ad for Intel’s mobile technology. The idea, I guess, is that she can get sumo commentary by wifi while watching the match. I pick up my laptop and check for wifi. None. She claps at the end of one match, and suddenly they’re gone.

Now the senior ranks enter the ring, and I actually recognize some faces – Asashoryu, of course, who enters with a sword bearer, but also Kaio, Chiyotakai and Kyokushusan, the first Mongolian to make it big in Japanese sumo. A father and son fill the seats to my right. He speaks some English, and we agree that we like the small guys best. (This is a trend in sumo. Five years ago, the really good wrestlers were huge bruisers, weighing in at 500+ pounds. Now the good sumo are comparatively lean, powerful guys, usually under 350. Asashoryu weighs about ten kilos more than I do, and is only slightly shorter. And the oldest competitive wrestler in Japan is 37, so there’s still time for me to make a career change.)

As the wrestlers are getting into place for the first match, the Vienna Boys choir arrives and files into the seats where the Intel people have left. They’re dressed in matching sailor suits, and are chatting, as young boys do, in a mixture of German and English. I figure out who they are when they start clapping in union. Only musicians clap that loud, like firecrackers breaking the semi-silence that’s accompanied the Juryo matches. (No, I’m serious. The Vienna Boys Choir. I’m listening to english-language commentary – the television broadcast of the matches in Hawaii – and they announce their presence in the stadium.)

I’ve been here for about two hours, watching several dozen matches, and I’m surprised at how much the action slows down for the main event. At this level, the start of the match is everything – a split second late and a 400 pound man is ramming his shoulder into your belly and you’re on your well-padded ass. The match begins when both wrestlers touch both

fists to the ground. So there’s a complex ritual dance, where one wrestler will take a position, fists down, and when it looks like the other wrestler is ready to drop his fists, the first will stand up, walk to the corner of the ring, grab a handful of salt and hurl it into the ring’s center. (The ring is a sacred space, and the salt purifies it for the combat.) In the juryo matches, this happens once or twice. In the Maku-uchi division, it’s a five minute process of half a dozen retreats, as the men feel each other out, looking for the right moment, a lapse in concentration, an opportunity.

And then both men put their fists down and it’s like an explosion. They grab each other, and it’s hard to tell if they’re hugging or trying to kill each other. And it’s over in an instant. Except when it’s not. If it lasts more than a few seconds, the men lock, the crowd holds their breath and starts clapping, and we wait for one of the two men to give. It’s unspeakably beautiful.

My rishiki do very, very well. Kyokushuzan wins a match he was expected to lose. Ama, a new Mongolian wrestler I haven’t seen before, destroys his highly ranked opponent. And Asashoryu, in the last match, dominates a much larger man to a degree that’s breaktaking. He grabs, turns his body into him, executes a perfect hip throw, and the day is done.

With three missions complete, it’s time to head home and save game. My feet are aching now – I took the insoles out of my shoes before leaving home (they smelled) and put in new ones, and they’re not good enough. I have blisters, and my legs are tired from the cramped seats. I take the train back to Akihabara, another train to Tokyo, where I discover the train I need to take to Chiba is 520m away underground. Ug. The trains aren’t marked in English and I’m guessing when I get on the one that appears to go towards my destination. I ask a passenger “Kaihin Makuhari?” and he gets up and RUNS out of the car, rather than face the embarrasment of speaking to me any further.

But a very distinguished looking gentlemen tells me that the train does, indeed, go to my stop, though it’s quite slow – a local. I thank him and sit down, reading my book and enjoying the ride until it appears that we’re going very slowly indeed. We’re stopped. And we stay that way for a long, long time.

As I’m beginning to worry about the train, my distinguished looking friend writes me a note, translating the messages being delivered in Japanese by the stationmaster. The first one reads:

“Power down far away. It may take for them to recover more time than we expect. It seems there is no other way than to wait.”

So I wait. Three notes into the conversation, I write back – “Should I get off and take a taxi instead?” I get a thoughtful reply advising patience. I’m awfully grateful – this is making the whole process of waiting a lot less anxiousmaking, so I do the one gracious thing I know how to do. I present my business card, formally, with two hands and a little bow.

He responds a moment later with his card. He’s a research fellow at the thinktank for the Yomiuri Shimbun, one of Japan’s best newspapers. He adds a note – “I have a friend at MIT.”

I spend the rest of the ride composing an effusive thank you email to him, which I just sent.

Mission complete.

Wednesday, May 11th

I’m a bit drunk. Let’s just put that out there as a disclaimer.

The best ways to encounter a culture – in my opinion – are a) to get drunk with people from said culture, and b) to watch local sporting events. If you’re lucky enough to combine the two, you’re likely in for a full immersion experience.

As you may have guessed at this point in the narrative (i.e., the last two years of posts), I’m not generally susceptible to culture shock. This is a learned, rather than inherited, trait. I remember being twenty years old, enroute to an entirely new life in Ghana, bumming around Scotland… and struck with nausea every time I saw a sign featuring prices in pounds and pence. There’s something about situations that are familiar… but just slightly… off… that’s far more disconcerting and shock-inducing than wholly unfamiliar situations.

(That said, wholly unfamiliar situations are what ultimately cure culture shock. Successfully navigate enough of them and you’re unflappable, vaccinated, immune. Mostly.)

I was supposed to spend today at the 14th World Wide Web conference, listening to a dozen academic papers and getting a sense for the current status of research on the Web. Instead, I spent about four hours at the conference, another four hours hanging out with T. at Joi’s house in a small village outside Chiba… and an additional four hours at Chiba Marine Stadium, getting extremely drunk with a small contingent of sararimen from the Sumitomo Chemical Engineering company.

(I love my life.)

Joi is possibly the only person I know who travels more than I do. He’s got a goal for this year – 100k miles on the three major carriers he flies. (Just by way of contrast, I’ll probably just break 100k on the one carrier I fly.) Like me, he’s an independently wealthy (self-made) international man of mystery who has no real “job”… but is constantly, insanely busy. We have a lot to talk about.

Joi is Japanese, but grew up in the US, mostly in a Detroit suburb, son of a Japanese auto executive. In his early business career, he lived in Tokyo – he’s now moved, with his fiance, to what he refers to as “rural” Japan. We drive for forty minutes in his black BMW through a set of small towns that look a lot like the northern suburbs of Boston – a few businesses surrounding a two lane road, houses behind them, tightly packed together. We stop for sushi at his neighborhood sushi bar, and I get to eat some of the best fish I’ve ever seen, wondering if this restuarant occupies the place in his life that the Old Forge plays in mine.

Joi’s house is surprisingly traditional for a guy who lives – to a greater extent than anyone else I know – online. While there’s wifi throughout, there are also tatami mats, floor chairs and a traditional deep bath. The house is thirty years old – the biggest in the “village” (by which I think Joi means the street the house is on), but to my eye looks like it could be a hundred. We walk around the backyard, kicking over bamboo sprouts so that his grove doesn’t get too overgrown, and I see the same sort of homeowner joy I feel pruning raspberry bushes.

On the other side of the bamboo is the village shrine, which burned down last year and was rebuilt by the son of the man who built Joi’s house. For a brief moment, I want to drop everything, learn Japanese and apprentice myself to a traditional carpenter somewhere in Hokaido. These feelings happen, They pass.

As much as I want to tease Joi about his “rural” lifestyle (he’s ten minutes drive from a train that puts him into downtown Tokyo in under an hour. Come live through a winter in western Massachusetts and talk to me about rural…), I feel an odd sort of kinship based on a love for the place you live. Joi wrote on his blog today about feeling stupid that he didn’t spend more time at home. I feel that way roughly as often as I feel grateful for the opportunities I have to wander the globe.

Joi’s on the road again, off to San Francisco. His fiance drives Tantek and me to the train station, and Tantek and I – two American geeks – are left to navigate our way back to Makuhari. Tantek takes photos of subway maps with his digital camera and consults them – I whip out printouts of diagrams of the train line that I’ve produced ahead of time. Realizing our shared geekiness, I unbutton my shirt and reveal that I’m wearing a t-shirt which reads: “$: cd /pub; more beer;” which reduces him almost to tears with laughter.

On a train filled with schoolgirls, we talk about something that’s made me very uncomfortable at times in Japan – the fetish for very young girls. Schoolgirls are groped so often on subway trains that Tokyo and Osaka have added special women-only cars to every train running during rush hour. Walking through the video stores in Akihabara, I’m stunned to discover that most of them include a category called “virginal photography”, which feature DVDs of photos of clothed young girls, often wearing bathing suits or tight athletic uniforms. The packaging features the age of the girls in question – most of the numbers I saw were between twelve and fourteen. All of this makes anime a bit more creepy for me…

After spending a couple more hours pretending to attend an academic conference, I undertake my main mission for the day – a Japanese baseball game. The Chiba Lotte Marines are hosting the Hanshin Tigers, and the stadium is directly behind the hall where the conference is held. I would dishonor my father’s baseball fandom by failing to attend the game.

The walk to the ballpark is one of the prettiest I’ve ever seen. Ballparks in the US are usually in the grungiest parts of town, where land is cheap. Walking to the ballpark – if it’s even a possibility – usually involves tripping over drunks and sacks of garbage. The walk to Chiba Marine Stadium involves a well-trodden path down a grassy strip lined with flowering shrubs. Given the walk to the park, I can only imagine how beautiful the park with be – graceful, landscaped, a subtle marriage of natural yin with baseball’s yang?

Uh, no. It’s the ugliest stadium I’ve ever been to in my entire life. (And yes, I saw the Expos when they were still in Olympic Stadium.) For those of you who don’t know, one of the most beautiful things about baseball is that there’s no “official” playing field. Yes, the bases are always the same distance apart from one another, and the mound from the plate, but the shape of the outfield varies wildly from park to park, giving each stadium its own distinctive character.

Chiba Marine Stadium has approximately as much character as an airport McDonalds. The field is perfectly circular. The outfield is perfectly symmetrical – 99 meters to right and left field, 126 to deep center. There’s no infield dirt, just small patches of dirt around the bases, and no warning track. I find the field deeply unsettling, like seeing a man without eyebrows.

Adding to my discomfort, the reasonably expensive seat I’ve paid for (behind first, where I insist on sitting) is “protected” by thick, black wire mesh, giving me the overall sense that I’m watching the game from inside a dog’s pen. (It’s all for the best that I haven’t gone for cheaper seats – they’re filled with uniformed members of the cheering squads for Chiba and Hanshin.) Plus, I haven’t been able to find a scorecard as I come into the stadium – I’m religious about scoring baseball games that I watch in person. And I’ve arrived at the top of the second inning, a sin roughly equivalent to showing up at mass when communion has already been served.

So I settle into my seat, meditating on the universal truth that, whether the field is circular or irregular, there are three strikes, three outs, three times three innings, and I can understand a baseball game perfectly well even if I don’t speak a phrase of the local language. I’m starting to understand why there’s no infield dirt – it’s a game for singles hitters, and a live infield means that a ground ball is more likely to become a hit. The pitching is bad – their best heat is around 85mph – but the hitting is great – really impressive contact hitting, putting the ball into play, even if there’s seldom a hit deeper than shalllow center field.

“Where you from?” asks the sarariman sitting to my left. “Boston”, I explain, pointing to the ball cap I’m wearing. “Boston Red Sox”.

“Ah, Boston Braves”.

I’m impressed by his historical knowledge, but suspect he doesn’t understand. I say “Red Sox” again, pointing to the dark socks peeking out from below his blue suit. He pulls my jeans leg up, points to my bare foot in my sneaker and announces to his companions, “No socks!”

We’re going to be friends now. One of the men in the party – there appear to be four or five men out for the night together, scattered in two rows to my left – goes to the concession stand and returns with four foil cups filled with hot sake. He offers one to me, announcing, “Japanese whiskey!” and I accept, bowing three times, offering my best “domo arigatos”. And I realize that I’ve now got two problems. My personal sense of honor won’t let me accept a drink without buying a drink, so I’ve got to go buy this man a cup of sake. And I’m already drinking a beer, and I’m hungry, which means that this cup of sake is likely to make me very, very drunk if I don’t put something in my stomach.

I leave my Sox cap on my seat, grab my briefcase, and head off to take insulin, buy a hot sake, some noodles and a couple of rice balls. I present the sake to my seatmate, which inspires a flurry of conversation in Japanese. Now my new friends are taking turns sitting next to me, trying out a few words of English, offering me edamame and asking my opinion of Japanese baseball players playing in the US.

“Ichiro?”

“Ichiro’s great. He’s probably the best hitter in the major leagues right now.”

And that’s the tipping point. Sake and beer keep coming my way, and my friends get increasingly chummy, putting their arms on my shoulders. I open my briefcase and present my business card, making sure to be formal, presenting it with both hands. I collect three business cards in return, discovering that I’m sitting with the executive committee of the Sumitomo Chemical Corporation. One of my new friends, settles into the seat next to me and explains, “I live in Houston for six months. Dow Chemical. Every night, Americans invite me to drink beer. I love Houston. So I want you to enjoy tonight.”

Not for the first time in my life am I glad for Texans’ natural generosity. The guy to my left is clearly a decent guy, and I’m proud in some deep, nationalistic way that the good ole boys in Houston showed him a good time. When he gets up in a few minutes to buy beer and hotdogs (served skewered on sticks), his companion sidles up to me and informs me, “The whole time he is in America, he drinks. He is drunk all the time.” But hey, the guy’s my friend, and I defend him, “Yes, but he has a very big heart.”

New guy is not nearly as personable as Houston-san. He makes a big deal of my German last name and ensures me that the Japanese and the Germans have been friends for a long time. Yes, I think, I seem to remember a war where Japanese/German friendship made a real impact on world affairs… He’s a racist as well. We get to talking about sumo, and I mention my love for Asashoryu. He says, “Ah, he is Yokozuna, but he is not Japanese.” I reply, noting that he’s Mongolian, and mentioning that he’s one of the youngest Yokozuna in history. And, seeing that it bothers him, I start rattling off my favorite sumo wrestlers… all Mongolians…

The night gets increasingly drunken. The Sumimoto boys aren’t big baseball fans. I’m doing my best to watch the game – which Chiba is winning decisively – and they’re clapping a few moments after I clap. But they’re excited by the pagentry of it all – the fireworks in the middle of the fifth inning, the Tigers fans launching yellow and white balloons into the air during the seventh inning stretch.

I’m of two minds. On the one hand, I’m having a good time with my new friends, and I realize that I’m going to have a good story and some great pictures. On the other hand, it’s not what I wanted out of a baseball game – the boys are interested in getting drunk and rowdy, not in rooting for Chiba. As we head into the ninth inning, Chiba leading four to one, I’m ready to go home. And when the Marine’s reliever retires their last batter, I’m outta there, bowing and arigato-ing, and moving at high speeds in the other direction.

I join the crowd walking to the train station. It’s orderly, calm and deeply weird – I keep waiting for someone to give a friend a high five, or to start one of the chants or songs that happened every time Chiba went to bat. But it’s calm, orderly and eminently Japanese.

Ahead of me, I see someone wearing a Green Bay NFC North Champions cap, and I have to say hello. I fight my way through the crowd, get close enough to tap the guy on the arm and say, “Nice hat. Go Pack!”

To my great surprise, he’s Japanese. (His hair is blond, and his skin is very pale, so, from behind, I’d assumed he was a misplaced Cheesehead.) He replies, “Go Pack!” and, pointing to the woman next to him – his mother, perhaps? – says, “She’s a very big fan. Last year, she went to San Diego to see a game.”

“I’ve been to Lambeau three times,” I tell them, and we stop, foot traffic parting all around us, to discuss whether this is Farve’s last year, whether Minnesota is more dangerous without Moss, whether we’ve got enough cornerbacks. It’s deeply weird, but also profoundly right – they’re fans, I’m a fan and the fact that we’re walking around Chiba is more or less irrelavent. We thank each other, bow, and walk on into the night.

I follow the crowd into the train station, hang a right and head into the mall at the heart of the complex where I’ve been staying the past three days. I have the worst Japanese meal I’ve ever encountered – breaded cutlet which I assumed were Tetsuo – pork – end up being some potato-like substance. I head home via the Chiba Marines souvenier store, stopping to pick up a Marines baseball for my father. And a fan emblazoned with the image of Bobby Valentine, formerly the manager of the Mets, now the manager of the Marines. Bobby, do you find it as weird here as I do? And as wonderful?

My photos of Japan are on Flickr: Chiba stadium, Joi’s house, the Tokyo Dome, Sumo, Akihabara, Tsukiji, and Harajuku.

Pingback: …My heart’s in Accra » Travel Writing

A comment (by the Velveteen Rabbi) clued me in on your story. Here’s an update on Gabe Kapler:

http://kaspit.typepad.com/weblog/2005/09/baseball_is_haz.html

Take care,

Kaspit

Thanks, kaspit. I’ve had a soft spot for Gabe since this experience. Hope he heals quickly.